“We’re living in a cloud forest…”

On days or afternoons when the view looks like this, a little song pops into my head, “We’re living in a cloud forest, cloud forest, cloud forest,” sung to the tune of “Moonshadow” by Cat Stevens. Living in the cloud forest is a particularly awesome experience. Each day, Parks and I discover at least one (usually more) amazing life form of flora and/or fauna that is totally new to us. We walk the trails of the reserve looking at and observing everything around us – you never know what the cloud forest might reveal at that moment. Reveal is a good word because some of the wonders of the cloud forest require a little time, patience, and/or luck in order to be seen, and of some you only find a trace.

On days or afternoons when the view looks like this, a little song pops into my head, “We’re living in a cloud forest, cloud forest, cloud forest,” sung to the tune of “Moonshadow” by Cat Stevens. Living in the cloud forest is a particularly awesome experience. Each day, Parks and I discover at least one (usually more) amazing life form of flora and/or fauna that is totally new to us. We walk the trails of the reserve looking at and observing everything around us – you never know what the cloud forest might reveal at that moment. Reveal is a good word because some of the wonders of the cloud forest require a little time, patience, and/or luck in order to be seen, and of some you only find a trace.

For example, can you spot the Lynch’s glassfrog in this picture? It flattened out its tiny body to even further camouflage itself on this palm frond. I’m not sure how Parks saw it.

And we only have seen hints of some of the more secretive and nocturnal mammals, like these footprints which we think belong to a jaguarundi, a small jungle cat. We set up a camera trap to try and capture a photo of it, but no luck.

Other gems of the cloud forest, are more reliably seen, like these guys, Andean Cock-of-the-rock.

The Andean Cock-of-the-rock displays twice every day – early morning and evening, year-round. At Las Tangaras, we are luckly to have a large lek, a displaying and mating area. We visit the lek at least once each week to observe them and record data on when they display, who is displaying (some birds are banded), where they’re displaying, who is friendly or aggressive with whom, and if a female shows up and some lucky guy gets to pass on his DNA.

As for mammals, we see lots of the two species of squirrel that are here and also get fairly regular visits from an agouti, a funny rodent about the size of a small dog, who sits and eats fruits in the yard.

While showy birds and bold mammals are more easy to see, shy birds, mammals, amphibians, and other animals can be more difficult to spot, mainly due to the abundant and lush cloud forest vegetation, which itself is amazing and wonderful to look at, discover, and try to identify.

A tiny Pleurothallid orchid in flower. The flowers which are less than 1 cm, arise from the top of the petioles.

Unlike the towering giants of the Amazon, the cloud forest consists of scattered large trees, with lots of understory shrubs, small trees, and a wide array of fern species, including the huge and prehistoric tree ferns. While the cloud forest is somewhat reminiscent of the classic Tarzan-like jungle with lots of things dangling off trees, it is different in that it is not so dark or enclosed, and while there are vines and lianas, many of the things dangling down are air roots from the vast array of epiphytes that grow on the trees and shrubs. Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants, but they are not parasitic; they get their moisture and nutrients from the atmosphere. Orchids, bromeliads, philodendrons, mosses, and lichens are just a few examples of the epiphytic plants found here. The forest has the appearance of being constantly decorated for a massive party with hundreds of garlands and flowers draped and hung in the trees.

You may be familiar with the opening line of Joyce Kilmer’s poem “Trees”, “I think that I will never see a poem lovely as a tree.” If trees are like poems, then the trees found here in the cloud forest at Las Tangaras are like rambling, free verse, epic poems.

It is perhaps impossible to convey in a photograph the enormous amount of plant life that can live on a single tree, but I’m going to try. Here’s a picture of a single tree, then a photo zoomed in on a section, then zoomed even more. Take a look at the trunk, it is just covered.

Las Tangaras Reserve helps to conserve a small section of the cloud forest found along the western slope of the Andes, but just like the Amazon rainforest, the cloud forest is also threatened by deforestation and the encroachment of farmland and cattle ranches. Across and up the river from Las Tangaras there is a new road and cleared area that provide a stark contrast to the lush landscape of the reserve. Here’s the view heading down the entrance trail to the lodge (you can just see the lodge roof in among the trees)…

The lodge is nestled down at the base of the slope. You can see the roof at the bottom, middle of the photo.

…and the view from the from the lodge porch…

…vs. the cleared area and road. Parks is standing in the new wasteland with all the topsoil exposed for easy erosion.

If one tree can hold such a diversity and magnitude of life among its branches, then it is difficult to imagine the number of species and amount of life lost when a whole swath of forest is cut down. What new animals or plant species yet to be discovered were lost? What rare or endangered life form lost its life or a little bit more of its habitat?

This is the reason that places like Las Tangaras Reserve are so important. Las Tangaras conserves an incredibly unique environment, while at the same time giving people the opportunity to visit and gently enjoy it. Hopefully, it impresses on each visitor the necessity of protecting such an amazing and special habitat. Walking among the immensity of plant life in the cloud forest surrounded by the chorus of bird, insect, and frog songs, catching sight of a brilliantly colored birds or even a glimpse of the rare mammal – this is an experience not to be missed or soon forgotten.

I’ll leave you with a fun set of photos that illustrate that you really never know quite what you will find when you peer into the corners of the cloud forest. We saw a leaf wrapped in gossamer threads and tried to see what was inside. First, with no flash…

…and then…

Hola! Somos Alexia y Parks…

Hola! We are Alexia and Parks, the new managers of Reserva Las Tangaras. We arrived in Mindo last Wednesday and were met by outgoing managers Marc and Eliana. We explored Mindo with them and met some very nice and helpful people around town. After buying some groceries, we caught a taxi to the reserve entrance. Hiking along the entrance trail we saw Choco toucans, listened to a golden-headed quetzal, and were awestruck by all the bromeliads, ferns, moss, lianas, and just overall abundance and diversity of vegetation. Every tree limb is covered by another universe, which in turn is covered by other little worlds. We arrived at the beautiful and cozy lodge where we were immediately taken by the chirping, fluttering, zooming flurry of hummingbirds at the feeders. So many and so many different species! Back in Virginia and North Carolina, we had been thrilled by the visit of the ruby-throated hummingbird to our feeder, now we can look forward to over sixteen different species of hummingbird.

After two days of training and wonderful conversations, meals and birdwatching with Marc and Eliana, we watched as they headed off down the trail and our time as managers of the reserve began. We now have a solid week behind us that has included a group of four Ecuadorians from Quito who trekked into the reserve in the rain and camped, and apparently loved their visit despite the rain. Our next visitors were Alex and Serena from Australia, who are doing a fabulous sounding tour of South America. We had a really nice time talking with them and also making really yummy meals for them. For dinner, we had sweet potato fries, lentil burgers, and a fresh veggie salad, and also gluten-free chocolate oatmeal cookies for dessert. Serena is gluten-intolerant, so I (Alexia) made up a recipe, and it worked out so great, I’ll probably try to make it again. For breakfast, we prepared scrambled eggs with tomato, onion, and pepper, and Parks made his amazing biscuits. We also made fresh passion fruit juice and had fresh, sweet papaya slices. Yum!

Parks and I have been enjoying starting the day with a cup of tea on the veranda while doing hummingbird data. Every day, we track the hummingbirds that visit the feeders, as well as the flowers around the lodge. So far, our favorite hummingbird is the Purple-Throated Woodstar because it is adorable and looks and acts like a slightly larger bumblebee.

The last few days have involved getting to know the water system, trail maintenance, cleaning, “mowing” the lawn (using a machete), and waxing counters. Along with daily caretaking, we are getting to know trails and learning birds. There is such an immense diversity of birds here, and quite a few of them look extremely similar, so identifying them is a bit of a challenge. We are already getting better, but there are a lot to learn. We are also enjoying the many incredibly colorful butterflies – several of which have really cool, transparent wings. As for mammals, we have seen an agouti, two different species of squirrel, deer tracks and bats. If you leave the hummingbird feeders out a little longer at dusk, bats come and drink, flashing in and out so quickly that it’s hard to distinguish all their features.

So far, Parks and I have been loving all of it. Our past experiences on tall ships, on farms, traveling in rural areas, backpacking, maintenance work, and cooking and caring for folks (Hello to Arthur Morgan School!) have given us a wealth of skills and helped prepare us to be managers of Reserva Las Tangaras. We are excited to share more about the reserve and our adventures here over the next three months! Please come and visit!

STOP… Hummer Time!

Perhaps our favorite activity during our time at Las Tangaras Reserve has been the appreciation and enjoyment of the bouquet of hummingbirds that frequent the flowers and sugar-water feeders placed around the cabin. I use the term “bouquet” as a fitting collective noun to describe a group of hummingbirds, as the harlequin beauty of their iridescent plumage when seen as a group can be likened to an exquisitely arranged bunch of brightly colored flowers. In the literature, a gathering of these feathered gems can also be referred to as a “glittering”, “hover”, “shimmer”, and even a “tune” of hummingbirds.

Over the past six weeks, we have been mesmerized and enchanted by these diminutive birds. The use of feeders and the strategic planting of their favorite flowers not only makes the hummingbirds easy to see but they can be seen really really well — to the point where it has become an obsession to marvel endlessly at their elegance and charm. Ritually observing the hummers and collecting detailed data on their diversity, numbers, and behavior is actually part of our official daily duties while managing the reserve. So… we don’t have to feel guilty about lounging on the rustic and cozy Las Tangaras porch, sipping a cup of Mindo-roasted coffee with binoculars in hand. Hey, it’s part of our job!

Hummingbirds are nectar feeders in the taxonomic family Trochilidae, which contains approximately 340 species exclusive to the New World (North, Central, and South America). Most of these are tropical, although 16 species occur in North America (even as far north as Alaska). In our regular home of Miami, we have only 1 to 2 hummingbird species that migrate south from their northern breeding grounds and spend the winters in South Florida (not unlike the human “snowbirds” from New York). In comparison, 130 hummingbird species occur in Ecuador, and over 20 different species make appearances right off the front porch of the Las Tangaras cabin (and there are around 30 species documented thus far on the reserve property in total). There is no evidence that hummingbirds need the extra food supplied in the form of sugar water at artificial feeding stations — or that they develop a reliance on it. In fact, most studies have shown that hummingbirds that use artificial feeders continue to forage the vast majority of time away from feeders, coming to them for only brief periods and then resuming their normal feeding behavior — typically a diet of 75% flower nectar and 25% insects. What the feeders have done to benefit hummingbirds is through their impact on people — by bringing humans closer to nature. Through feeders, we are better able to appreciate, love, and understand hummingbirds, and this in turn fosters a human connection to the natural world that for most people is lacking.

We have come to learn and delight in the unique personalities, vocalizations, and the identifying features of the many characters in the Las Tangaras hummingbird extravaganza.

Here are a few of our favorites.

Purple-bibbed Whitetip (Urosticte benjamini)

This small hummingbird is one of the bravest and dare we say, cutest, at Las Tangaras.

It shows little fear of humans and will often land on our hands and fly right in front of our faces when we are putting out the feeders. Believe it or not, it has even attempted to probe its tiny bill into our ears and nostrils looking for nectar.

Several of the hummingbirds at Las Tangaras have been leg-banded through LifeNet Nature’s mist-netting research projects, and sometimes we can view this species from such a close distance that we can actually read the tiny numbers on its metal bands.

A close look at this female whitetip’s right leg reveals a tiny metal leg band with a unique numerical code. We affectionately call this individual “fifty-seven” as 5 and 7 are the last two numbers on her band. Can you make out the upside-down 7?

The unmistakable male has a large patch of glittering purple on its mid-chest, a glittering green gorget (throat patch), and unique broad white tips on the central feathers of its deeply forked tail. A short but bold white post ocular stripe is also prominent.

Interestingly, the iridescent feather colors in hummingbirds are largely caused not by pigmentation — but by microscopic feather structure — and thus are dependent on the angle of the sunlight for the colors to be properly reflected. At the “wrong” angle, a hummingbird might look completely black, but then the bird turns and suddenly an incredible flash of color appears.

Male purple-bibbed whitetip, in the “wrong” light, where the glittering purple bib and green gorget cannot be appreciated. Look at those white tail tips, though!

The female, who looks quite different, also has a bold white post ocular stripe as well as a thin white malar stripe, and is white below thickly spangled with glittering green. Her tail has narrow white tipping only on its outer feathers.

A distinctive behavior of these birds is that often after landing, they will stretch their wings out in a “ta-da!” like motion.

On left, a male purple-bibbed whitetip raises its wings in the typical “ta-da!” fashion immediately upon landing. Interestingly, an immature male on the right looks similar to the female, though he has a buff tinge to the fore neck area. This confused us a bit at first, until we consulted Las Tangaras’s library of bird books!

They often sing their way to their feeders with a high-pitched mouse-like squeak.

To the untrained eye, a female purple-bibbed whitetip could be mistaken for other female hummingbirds such as this female green-crowned brilliant, below. However, note the marked size difference and subtle differences in plumage and bill shape. Making these distinctions becomes second nature given the amount of time we spend watching these birds!

Rufous-tailed Hummingbird (Amazilia tzacatl)

A medium-sized noisy hummingbird and also one of the more numerous in Western Ecuador. Its color is mostly green but its entire tail is contrastingly rufous. Additionally, it has a distinctive reddish-pink bill, brighter towards the base and blacker at the tip.

Males and females look alike with only very minor differences. Here, it is affectionately known as our “machine gun chatterbox”, owing to the loud sputtering noise it makes that gives away its presence. However, this noise is not a vocalization; rather, it is actually a “wing whir”, or buzzing sound it makes with its wings.

They defend food sources quite aggressively and can often be found starting a war at the feeders.

Empress Brilliant (Heliodoxa imperatrix)

A large and truly regal species of hummingbird that has a commanding presence at the feeding stations is the Empress Brilliant. The spectacular male is mostly green, with glittering golden green on its belly and a violet-lavender gorget. Its tail is very long and extremely deeply forked. Additionally, its head is relatively large with a protracted bill.

The female also has a long forked tail and a glimmering golden green belly, but she also has a white malar streak and her throat and breast are spangled with green discs.

Immatures of both sexes show rufous on the chin and malar area (as do young of all the brilliants)

In comparison, the similar Green-crowned Brilliant (Heliodoxa jacula) is smaller, has a shorter tail lacking a deep fork, and in neither sex does it show the golden cast to the belly. The female Green-crowned Brilliant also has a white tip to the tail, which the Empress does not.

Examine the two birds with their backs toward you. Left, empress brilliant male, showing long deeply forked black tail. Right, male green-crowned brilliant, showing smaller notched blue-black tail.

Green-crowned Wood-nymph (Thalurania fannyi)

Undeservingly, we sometimes refer to this small bird as our “default” hummingbird. New visitors to the reserve trying to sort out the many species of hummingbirds seem to get caught up on this one. As they are quite numerous at the feeders and can often look nondescript in poor lighting, if you don’t know what it is, chances are it’s a green-crowned wood-nymph!

They land on the feeders and when not feeding, can often be found perched in groups of 3 or 4 on the branches placed off the porch. The male can often look quite dark, but in the right light it’s actually one of the most beautiful iridescent birds seen here. He has much glittering green, including the crown, throat, and chest, the latter contrasting with its glittering violet-blue underparts. Its tail is rather long and deeply forked (more noticeable in flight).

The female is smaller and much drabber, with distinctive two-toned underparts. Its rather pale gray throat and chest contrast with much darker mixed green and dark gray breast and belly.

White-necked Jacobin (Florisuga mellivora)

Some of the interesting trivia surrounding hummingbirds revolves around the elaborate descriptive names that they’ve been given over the centuries. The different hummingbird groups, or genera, have been given ornamented fantasy-like names that conjure up make-believe worlds akin to Lord of the Rings. Among the different kinds you’ll find pufflegs, trainbearers, sylphs, coquettes, coronets, wood-stars, sapphires, hillstars, firecrowns, sabrewings, sunangels, violetears, topazes, racket-tails, star-throats, metaltails, fairies, and mangos, to name a few. Someone must have had a grand old time sitting in a dark basement with a set of Dungeons & Dragons dice, a bag of Funions, and a Rush tape pounding in the background, inventing these extraordinary fantastical names. So it occurred to us, how did the White-necked Jacobin get its name, and what the heck is a Jacobin anyway? The answer was not so simple…

The White-necked Jacobins were not always called jacobins. In fact, the father of British ornithology in the 1700’s, George Edwards, whose plates and descriptions provided basis for the scientific name given the species by Linnaeus fifteen years later, simply called it the “white belly’d hummingbird”. That common name was used through the early 1800’s, when another prominent English zoologist, George Shaw, took nomenclatural cues from the French ornithologists’s name for this bird, “oiseau-mouche á collier”, and translated this into English as “White-collared Hummingbird”. This dull name stuck for many years, but what the Brits didn’t know at the time was that the French had given this bird TWO names. In the 1800’s French text, Histoire naturelle des oiseaux, the bird is depicted as “oiseau-mouche á collier — dit la Jacobine”. French ornithologist Buffon wrote, “It is, obviously, the distribution of white in the bird’s plumage that gave rise to the idea of calling it Jacobine.”

The White-necked Jacobins were not always called jacobins. In fact, the father of British ornithology in the 1700’s, George Edwards, whose plates and descriptions provided basis for the scientific name given the species by Linnaeus fifteen years later, simply called it the “white belly’d hummingbird”. That common name was used through the early 1800’s, when another prominent English zoologist, George Shaw, took nomenclatural cues from the French ornithologists’s name for this bird, “oiseau-mouche á collier”, and translated this into English as “White-collared Hummingbird”. This dull name stuck for many years, but what the Brits didn’t know at the time was that the French had given this bird TWO names. In the 1800’s French text, Histoire naturelle des oiseaux, the bird is depicted as “oiseau-mouche á collier — dit la Jacobine”. French ornithologist Buffon wrote, “It is, obviously, the distribution of white in the bird’s plumage that gave rise to the idea of calling it Jacobine.”

However, look closely — the French name is originally feminine, referring not to the Dominican (Roman Catholic order founded by St. Dominic) monks of St. Jacques but to their female counterparts. Hence, this brightly colored male hummingbird is named for the resemblance of its plumage to the garments of a French Dominican nun. For reasons unknown, when jacobine was subsequently translated back into English, the terminal “e” in the word was dropped, hence transforming the feminine “jacobine” into the masculine “jacobin”. So, you can add both the White-necked Jacobin and the Empress Brilliant to the list of extraordinary Las Tangaras male hummingbirds with a gender identity crisis!

On a closing note, whoever sold us these “hummingbird” feeders clearly wasn’t painting the complete picture. After the sun sets over the Andes, while hummingbirds are quietly dreaming of endless fields of nectar-rich flowers, their winged counterparts of the night emerge from their roosts…

Text by Marc H. Kramer; Photos by Eliana Ardila

Life in the Tropics

Marc and Eliana hike up one of the many refreshing streams on the Las Tangaras Reserve

Greetings! Saludos from a new duo of intrepid Las Tangaras managers, Marc Kramer & Eliana Ardila. To introduce ourselves, we hail from Miami, Florida (USA), though Eliana is a native Colombian (from Bucaramanga) and Marc is originally a New Yorker (Long Island). Our backgrounds lie in veterinary medicine, field ornithology, zoology, and nature appreciation in general. We’ve been together as a couple for 8 years and travel regularly in North, Central, and South America, wandering the globe with an insatiable appetite for experiencing new biomes, cultures, foods, landscapes, and adventures. Having a fervent love for the tropics and its avian fauna, we are also passionate birders and are greatly looking forward to the vast potential of the Ecuadorian cloud forest in turning up new birds for our life list and all manner of animals and plants.

In front of the rustic Las Tangaras cabin

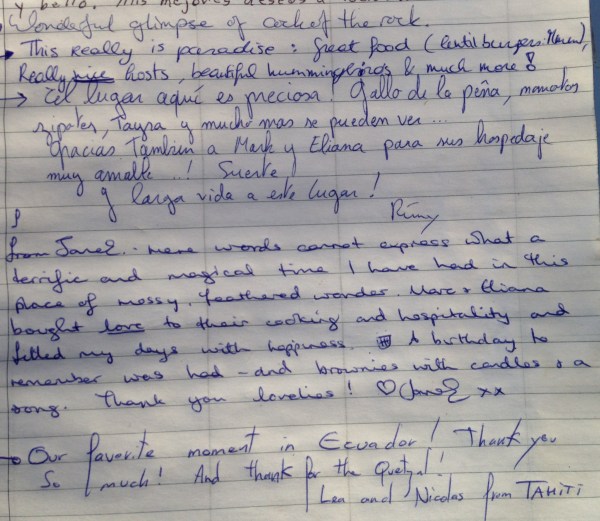

With two weeks behind us at Las Tangaras thus far, we can definitely say life in the tropics has been extremely busy. Outgoing managers, Jo and Hamish, overlapped with us for two days and gave us an intensive crash course on running the reserve. Not long after their departure, we quickly welcomed a myriad of enthusiastic new visitors. We had house guests from Belgium, England, France, Australia, and even an adventurous couple from French Polynesia (Tahiti).

While our new friends hiked the many reserve trails and spotted wildlife such as coatimundi, tayra, golden-headed quetzals, and Chocó toucans, we stayed hard at work in the kitchen cooking a cornucopia of flavorful homemade meals. Some of the favorites that will likely make a regular appearance on the

Empanada master Marc hard at work in the kitchen

Las Tangaras menu included vegetarian bean curry, meatless lentil burgers topped with fresh avocado, cloud forest pasta primavera, tropical Caribbean soup, quinoa bowl breakfast, and Colombian-style empanadas made from scratch!

When we weren’t creating culinary masterpieces, we kept our international company engaged in a number of other ways. Both of us guided early morning tours to the Andean Cock-of-the-Rock lek, where visitors can witness firsthand the rambunctious iconic bird of the South American cloud forest and its incredible courtship behavior. Hummingbird identification sessions on the front porch were a big hit and our guests left with a good grasp on discerning the 12 or more vibrant species regularly seen at the feeders.

Purple-throated Wood-stars… Green-crowned Brilliants… Brown Violetears … the potpourri of colorful hummingbirds here is like a bowl of Lucky Charms!

A female green-crowned brilliant eagerly awaits a meal of high-energy sucrose. Look closely to see her micro leg band.

We celebrated a birthday for one of our multi day visitors, Jane Hulland, and baked an amazing batch of birthday-candle-topped melt-in-your-mouth brownies for her using locally produced cocoa from Mindo’s El Quetzal Café. Que rico!

One morning, three of us hiked the Patos and Colibri trails to the “Three Teacups” and delighted in a refreshing dip in the trinity of cool tropical pools.

The edges of the nearby streams and the Nambillo River are teeming with fluttering butterflies of all colors and sizes, as they feed on salty stream residues and even the droppings of other animals. Frogs appreciate the watery environment as well and can be found in both adult and tadpole form in and around the streams.

We’ve developed a particular fondness for the avian inhabitants that have an affinity for streams: the white-capped dipper, torrent tyrannulet, green-fronted lancebill and black phoebe — though we’re still holding out for our first torrent duck. Photographing these water-loving birds has been challenging and will hopefully be featured in a future blog post.

Despite the hard work involved, we really enjoyed our company from all over the world. We reveled in the opportunity to share our excitement and appreciation for the flora and fauna of the Neotropics and savored the challenge to cook three delicious meals a day for up to five people at a time. Best of all, we made some new friends!

Eliana (middle), with Nicolas and Lea from Tahiti, excited after spotting a golden-headed quetzal on the trails

Jane (England), Eliana, and Skye (Australia) catch a glimpse of morning sun — a precious commodity in the montane cloud forest!

It’s great to hear positive feedback on the reserve and that our efforts are really appreciated! A few recent quotes from the Las Tangaras guestbook:

And now for some down time… Eliana has discovered her favorite place to relax and photograph — the bridge over the Nambillo River. Hasta luego!

Marc & Eliana

Migratory Birders

The biggest event of July at Reserva Las Tangaras was the arrival of Dr Dusti Becker and a team of volunteers who flew down from North America for a short season of birding at the equator. For Jo and I the arrival of these guys was even better than suddenly finding yourself in the middle of a mixed flock of tanagers on a forest trail in the shafts of morning sunlight.

For two weeks the cabin and trails at Reserva Las Tangaras were full of new friends, laughter, songs to Larry’s guitar, and discussion, especially about birds. Our days began alarmingly early at around 4:30. Beams of headlamps swept around the cabin as people dressed and made their way from the communal sleeping quarters, downstairs to breakfast by candlelight. Two Ecuadorian couples regularly help Dusti with birding research. The men, Pascual and Mauricio are experts at handling birds, while the women, Jessica and Alicia are experts at feeding people and keeping houses in order amidst their families, or birders.

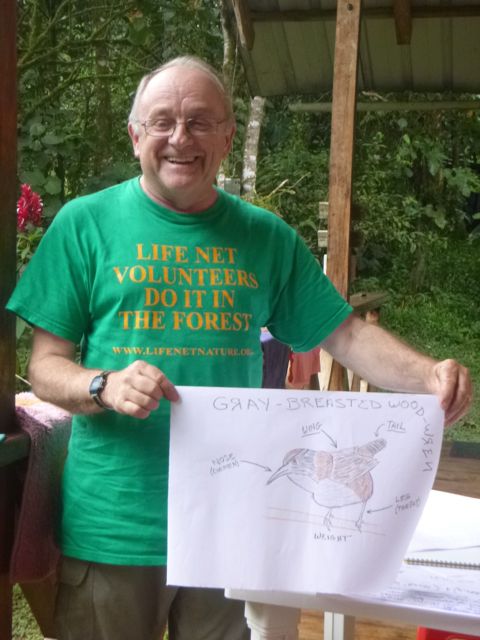

Still before dawn we packed up our snacks, donned our rubber boots and walked out into the reserve to open mist nets just in time to catch early birds, but not so early as to catch too many little furry, leathery, sharp-toothy bats. Captured birds were released from the tangled locations in 30 nets every half hour, until we closed the nets in the warmth of the day, an hour before noon. Placed in cotton bags the birds were returned to banding stations where we recorded species, ages, sexes, all manner of measurements and the presence of any ectoparasites. Birds without leg bands were given them, each with individual numbers, and previously banded birds had their numbers noted. The object of the ongoing research (since 2005) at Las Tangaras is to gain longitudinal information about the composition of bird communities at several established sites on the forest edge and in the deeper forest within the reserve.

On one day of banding the birding team was visited by a group of teenagers travelling with National Geographic Student Expeditions. Many were fascinated by the up-close contact with birds that the banding experience provides.

For Jo and I birding and banding with birders has been a lot of fun. We’ve learned to recognise the songs of several species in the forest around us and we have closely observed and handled many species. They have now become much better-known neighbours.

While our highlight for the month was definitely the half of it that we spent with the birding crew, July at the reserve was also busy in other respects. Jo managed the construction of a new shower, floor and wall in the bathroom of the cabin. A new septic pond was constructed after the existing one choked on its substantial contents. I walked all of the reserve’s trails with a GPS unit to create a new map and Jo’s new flyers advertising the reserve were printed in Quito and we began distributing them in Quito and Mindo. Time for us at the reserve has flown, like the departing North Americans. We are determined to make the most of our final few weeks here.

Seasonal changes

The forest canopy over the reserve provides requirements for niches of numerous plant and animal species. We’re frequently straining to spot a small bird calling high in the foliage or admiring a tree festooned in a hanging garden of epiphytes. Walking along the trails, particularly in previously disturbed forest, we are sometimes stopped suddenly as something big crashes through the leaves overhead – a monkey, a guan? Falling down through the layers of forest it is a cecropia leaf 60cm across, palmate like a hand, with a long heavy stem that makes the leaf plummet like a stick. The plants and animals become familiar to us.

In June we recorded 132 mm of rain, less than one fifth of the quantity that fell in May. As the season changes many canopy trees and vines, epiphytes, shrubs and herbs are flowering more prolifically than they did the month before. This reproductive effort is a boon to insects and birds whose niche includes collecting payments of nectar from flowers in return for pollination services. This month the hummingbirds have found more nectar all over the forest so the feeders at the front deck of the cabin are relatively less attractive to them. The regular rush of this bar’s happy hour that Jo records at the end of the each day has been quiet, a little bit lonely.

One morning Jo found clear cat prints along the beginning of the Quetzales trail. Our guest Danielle later found more of the same prints treading up and down new steps at the top of the trail in the freshly disturbed soil. After some research they concluded that the prints belonged to either an ocelot or a jaguarondi – quite big cats! Exciting. On our next visit to town we bought a chicken leg for bait and a stack of D-sized batteries to power up the reserve’s boxy camera trap with its bright flash and motion sensor. Every evening for about two weeks I put out the camera and the increasingly foul-smelling chicken leg. The results: no cat. Only gangs of tank-like scarab beetles chomped great holes in the chicken leg and they were joined at the feast by primitive carrion beetles, large butterflies and of course, flies. Scarabs have become favourites among the insects at the reserve with their animated antennae, shiny VW exteriors, trundling progress when walking and surprising flight. Amongst the most entertaining characters were a tiny dung beetle in metallic-green rolling a ball of precious poo along a trough of corrugated iron and a massive 41 mm beetle who had hidden on the forest floor. As for the cat, it wasn’t so surprising that it didn’t show for the photo shoot given that they range over a large territory. Jo found more of the same prints several weeks later on the other side of the reserve.

July is holiday season both in Ecuador and in the USA, so Mindo and Reserva Las Tangaras will become busier with keen bird watchers. Dr Dusti Becker will bring a team of birding volunteers for two weeks from the middle of the month. We’re looking forward to learning masses of ornithological facts and bird-researching skills from these avian enthusiasts as well as chatting about their experiences of home and travel. It promises to be a great month at Las Tangaras.

Los Nuevos

Hi there! My name’s Hamish. Jo and I are from New Zealand and we’re managing Las Tangaras until late August. We first heard about the reserve around 18 months ago when we were in a tramping hut (that’s Kiwi for “trekking cabin”) in Arthur’s Pass in New Zealand’s South Island where we met Bex, who managed the reserve in 2011. It’s great to now be here ourselves!

We arrived to a warm welcome from Corey and Niki, who introduced us to some of their favourite locals, made us beds and dinner and showed us how things work around the reserve. They had recently re-named trails in the reserve at Dusti’s suggestion. Niki chose names from birds she had seen on each trail so we now have ‘Los Tucanes’, ‘Los Colibríes’, ‘Los Momotos’, ‘Los Patos’ and ‘Los Quetzales’. The ‘Bosque’ and ‘Gallo de la Peña’ trails remain unchanged. The day after we arrived Danielle also came to the reserve. She’s a Californian who has been studying in Quito for a semester and is staying with us for five weeks, doing research on hummingbird interactions, amongst other things, as part of her studies for her college in Maine.

For me, living here is a remarkable opportunity. Tropical forests with their enormous species richness continue to be cut and compromised all around the girth of our planet. As a global community we lose the contained biodiversity forever. I think part of the reason why tropical forests continue to be eroded so quickly is that most people have no way of relating with them or their inhabitants and therefore have little reason and unclear means to conserve them. Most of us don’t consider tropical forests in our day-to-day lives. So I’ve often wondered, what are valid ways for those of us who normally live in cities or closer to the poles to personally relate with tropical forests?

Jo and I are excited about our stay in the 50 hectare Reserva Las Tangaras on the edge of a 19 200 hectare forest reserve called Bosque Protector Mindo-Nambillo. Part of the excitement for me is getting to know a few of the animal and plant species in the brilliant display of life here. People attach names and therefore importance to the species they relate with. Reserva Las Tangaras has a small library of great guidebooks to the names and human uses for many plants and animals in South American topical forests. So we are reading and looking and learning every day.

Jo has taken a shine to the hummingbirds and has become the best at identifying them. About twelve species commonly visit the feeders at the front deck of the house we live in. Jo frequently informs them that “You are all beautiful!” Here in the cloud forest on the shoulder of the Andes there are much greater numbers and diversity of these stunning little birds than down in the rain forest of the Amazonian lowlands to the east.

I’m getting a handle on identifying plant families as we maintain trails around the reserve. I’m fascinated to learn how many members of these groups my community and I back in New Zealand use daily as food and medicine. Strange, beautiful insects and myriapods walk, eat, hunt and find mates all over the assorted foliage in the reserve and I have enjoyed photographing these over the last couple of weeks. For three months Jo and I get to relate closely with this patch of tropical forest as managers of the reserve. Maybe our new understanding of the inhabitants can also sustain a longer-term relationship with and appreciation for their home. Maybe our means to conservation from afar could be in supporting others who conserve reserves or in encouraging others to undertake eco-tourism in places like Mindo, Ecuador, so that locals more highly value the biodiversity on their doorsteps.

The sun has been sparkling through blue skies in the mornings here, almost, but not quite enough sun to dry the clothes and linen we wash by hand. The forest cloud and afternoon rain enable lush vegetation to grow outside the house and moulds to establish on neglected surfaces within. We carry machetes on every walk to clear vegetation from trails. On the steep, slippery parts of wet tracks we build steps from fallen logs and drift wood collected from the edge of the Nambillo River. The smaller tributary that is the source of our water is a beautiful series of cascades and pools that support dippers, insects and tiny, exquisite frogs. The stream also frequently rejects the water pipe that carries water to the house, thereby necessitating frequent admiring or disgruntled visits by the inhabitants of the house to re-establish the flow. In Ecuador this cloud forest to the west of the Andes is currently transitioning from the wet season to the dry, so we are seeing more and more sunshine as the days go by, making this is a great time to visit! There’s even a chance of spotting Ecuadorian white fronted capuchins – we’ve seen them twice near the house this week. The trees here are home and life for those primates so they don’t think about the validity of their relationships with tropical forest!

As some of you may remember, towards the start of our Las Tangaras adventure I broached the subject of the White Fronted Capuchins (Cebus albifrons) that have been regularly seen on the reserve as potentially being the Critically Endangered sub-species Cebus albifrons aequatorialis. The Ecuadorian capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis) is a critically endangered primate found only in the fragmented forests of western Ecuador and northern Peru, which are among the world’s most severely threatened ecosystems.

After finally encountering the monkeys while I had my camera and conducting a little research into the topic I am now certain that the species that calls Reserva Las Tangaras home is The Ecuadorian capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis). This, once more, proves the value of the reserve as an important conservation area. The fact that these animals are regularly seen in the vacinity of the Andean Cock of the Rock Lek also raises a few questions that future research on the reserve may potentially answer. I only wish I had the time here to do it myself. I have developed a bit of a passion for primates after a year and a bit in South and Central America and may potentially follow this up academicaly.

.

Ultimately there is only one main point from which I need to draw my conclusion, comparative distribution. The primary cause of the speciation of the Ecuadorian White Fronted Capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis) is that the Andes Mountains have become a natural barrier and seperated Cebus albifrons from the Cebus albifrons aequatorialis with the former residing in the Amazonian forests to the East while the latter has developed in isolation between the Andes and the coast to the West. As Mindo is on the Western slopes of the Andes it is fair to say that these monkeys must be the Cebus albifrons aequatorialis.

For more information on this sub species please read:

http://tropicalconservationscience.mongabay.com/content/v5/TCS-2012_jun_173-191_Jack_and_Campos.pdf.

Sounds of Las Tangaras

We humans are known to have 5 senses; touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing. To date this blog has centred on one of these, sight, very thoroughly and we have shared countless words and photographs in an attempt to give our readers some kind of insight into life at Reserva Las Tangaras. As effective as this form of communication has been there is one sense that we have access to over the internet that has been unknowingly neglecting over the years, that of hearing. When it comes to Las Tangaras, hearing is stimulated at least as much as our sense of sight, if not more, and any description of the experience that is Las Tangaras could never be complete without the sounds of the reserve being given a fair representation.

The following blog includes recordings some of the more vocal wildlife that can be found at Las Tangaras. Each of these species have been heard numerous times during our time here and will forever be a part of our memories of Las Tangaras.

Pinnochio Rainfrog (Pristimantis appendiculatus)

Purple-Bibbed Whitetip (Urosticte benjamini)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/163520/download

Chestnut Mandibled Toucan (Ramphastos swainsonii)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/163511/download

Golden Tanager (Tangara arthus)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/165862/download

Pastures Rainfrog (Pristimantis achatinus)

Watchful Rainfrog (Pristimantis nyctophylax)

Andean Cock of the Rock (Rupicola peruvianus)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/175046/download

Emerald Glassfrog (Esparana prosoblon)

Pale-mandibled Aracari (Pteroglossus erythropygius)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/120027/download

Confessions of a Las Tangaras Camera Trap

As there is no electricity at Las Tangaras, the sun defines our days. The sun rises and wakes us, lights our journey through the day and then when the sun disappears, it lets us know that it’s time to relax and unwind. During the day, while we go about our daily chores, we a privy to a huge amount of avian, mammalian and herpetological species and we are constantly kept in a state of wonder with each new encounter. You would think this would be enough for us…. But you would be wrong. We needed to know what was prowling the darkness after the doors of the lodge were firmly closed. So, with the help of our trusty camera trap, we delved into the Las Tangaras nights. This is the result of our first 2 weeks camera trapping.

Central American Agouti (Dasyprocta punctata)

Although we have an Agouti that regularly visits our back yard, so regularly in fact that we have named him Frugal, we had no real idea of how many Agoutis were occupying Las Tangaras and in what habitats. Based on our preliminary photo trapping we have found Agoutis to be numerous and widespread throughout the Riparian and Secondary Forest habitats. Most of our camera trapping records are from between the hours of 4.30pm and 6pm with the addition of occasional daytime observation.

This species of Agouti is the most widespread in the Americas, distributed from Mexico down into northern South America.

Oncilla (Leopardus tigrinus Spp. pardinoides)

By far our favorite and most exciting camera trapping result is this one of a small Oncilla. This tiny jungle cat was photographed in Secondary Forest cautiously coming in to check out the cows digestive tract that we were using as bait. Given that this species is known to have a territory of only 2km squared it is safe to assume that the majority of this animal’s territory, if not the whole thing, is contained within Las Tangaras.

Footprints for this species were also found a day after this photograph was taken only 50m from the house. These tracks measured less than 5cm in length which gives you some idea of how small these cats actually are. This cat is know to eat small mammals, lizards, birds, eggs, invertebrates, and the occasional tree frog which is good… because there is an abundance of all of these within Las Tangaras. Oncillas are typically distributed from Costa Rica through to Northern Argentina, and show a strong preference for montane forest.

This species is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

Paca (Cuniculus paca)

Although they look rather similar, with the obvious exception of the stripes, the Paca is not as common as the Aguti within Las Tangaras. In fact, this is the first of 2 we have observed here. This animal was photographed in Riparian habitat, attracted by the bait of egg and banana that we were using at the time.

Interestingly, Pacas originated in South America and are one of the few mammal species that successfully emigrated to North America after the Great American Interchange 3 million years ago. Their similarities with Agutis mean that they were formerly grouped with the agoutis in the family Dasyproctidae, subfamily Agoutinae, but were given full family status because they differ in the number of toes, the shape of the skull, and coat patterning.

Black Eared O’Possum (Didelphis marsupialis)

The scavenger of the forest, the O’Possum has appeared in every single trapping period in which we used meat in the Secondary Forest habitat. Wherever present, they increase the survey effort required by us because they come in and eat all of the bait in the first few hours, therefore removing the incentive for other species to come in to the camera trapping site. Although frustrating at times, this is still the first time we have seen a wild O’Possum on our Journey so it was still pretty exciting.

This opossum is found in tropical and subtropical forest, both primary and secondary, at altitudes up to 2200 m.

Stay tuned for more Confessions of a Las Tangaras Camera Trap.