Snakes, Snakes, Snakes

Mindo is a paradise for nature lovers, specifically birders. The past few months we’ve learned more than we thought possible about the bird life here. With around 611 species already being spotted this month in the Pinchincha region (eBird), make no mistake, birds are king. However, sometimes they’re a bit out of touch. Always flying away, perching high up in the branches of trees, mocking you with their cackles. The shining stars of the past few weeks have really been those that skulk, camouflage, and slither on the forest floor: snakes!

While avian lovers may be remiss with this topic change, I encourage my fellow herpers to buckle up for this barrage of serpents, big, small, and venomous.

One of our most surprising finds was the Andean Snail Eater (Dipsas andiana), which was found foraging behind the cabin on a rainy night during a compost run. They don’t only eat snails as the name suggests, but will also eat a slug or two (close enough). These guys have a distinct blackish U-shape on their heads and very blunt snouts. Despite being vulnerable, they can be found quite frequently (every few nights) in Mindo during the rainy season.¹

If you thought the snail-eater had a certain weird energy that could not be beat, the Common Blunthead (Imantodes cenchoa) will give you a run for your money. This is the pug of snakes, with its bulging eyes taking up to 25% its head space. Of course it manages to impressively eat lizards (primarily Anolis), frogs, and eggs of other herps with its impressively small head and thin body.² We have only seen it once, but it is a common arboreal snake in Ecuador, which you may have discerned from its “common” name, given the strangeness of its appearance.

Up until now we’ve only seen the previous snakes once, however, the next snake we have seen twice now, three weeks apart. That would be the Humpback Shadow-snake (Diaphorolepis wagneri), which is normally seen at a rate of once every few months. Why this cryptic beauty graced us with its presence twice, we will never know. So cryptic it is, that scientists are not even certain what it eats, however they presume lizards!³

When there is sun, there must also be snakes. In the cloud forest, the sun is a limited resource. Taking advantage of the little sun we’ve had, we managed to find three snakes of two different species, the Rainbow Forest Racer (Dendrophidion clarkii) and the Golden-bellied Marsh-Snake ((Erythrolamprus albiventris). Both of these snakes have aglyphous dentition, meaning their teeth don’t have the proper gear to deliver venom. Because of this, they observe the true meaning of “fast-food”, eating prey quickly before it escapes.⁴ ⁵

Just when you thought we were done, there’s one more find that takes the cake. At the ungodly hour before 6am, just as dawn had broken and before I had my coffee, Jonas and two guests discovered a very contemplative Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli) enjoying the trails. These vipers are distinguished from their more aggressive cousins the Fer-de-Lance (Bothrops asper) by their slightly upturned heads, smaller eyes, and heat-sensing pits next to the nostrils. These snakes are only seen once every few months, and are considered vulnerable.⁶

As you can see, the reserve has a lot to offer. It’s a haven for snakes from common to vulnerable, with eyes large and small, throughout the night and day!

Disclaimer: Please never pick-up or touch any wildlife, especially snakes.

Resources:

¹Arteaga A (2024) Andean Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas andiana). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ERHE2385

²Quezada A, Molina-Moreno T, Aponte-Gutiérrez A, Duque-Torres D, Acosta-Ortiz J, Arteaga A (2024) Common Blunt-headed Snake (Imantodes cenchoa). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/AURT2841

³Arteaga A (2024) Humpback Shadow-Snake (Diaphorolepis wagneri). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/JXXF4716

⁴ Arteaga A (2023) Rainbow Forest-Racer (Dendrophidion clarkii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/COND1023

⁵Arteaga A (2024) Golden-bellied Marsh-Snake (Erythrolamprus albiventris). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/LLLF9348

⁶Arteaga A (2020) Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: http://www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZBMA5522

In the Garden of Loneliness

People tend to equate the term “remoteness” with “loneliness,” as if all the major cities and suburbs in the world offer the opposite. However many people exist in the space around you, does not guarantee connection. The first few weeks here at the reserve, I believe we were burdened by the same assumption. Only having one other person to listen to all of your ideas, deal with all of your idiosyncrasies, and tolerate your off-key singing, sounds like a challenge. Alone time is key, and once you leave the presence of some you find solace in others.

But what others, you might ask? Grab your yellow rain boots, and join me for a walk on the reserve.

First, as you enter the forest, there is a quiet stillness that blocks the rushing of the Rio Nambillo. You continue walking to find that the ferns and grasses, despite our constant maintenance efforts, have started winding playfully into the trail. Welcome to the cloud forest, you think to yourself. You start ascending quite rapidly, sweating because of course you brought your rain jacket but it hasn’t rained. Somewhere in the bushes, the three-striped warblers make soft high-pitched calls to beckon your arrival. In the distance, the Yellow-throated toucan is chiming in with its incessantly loud yelps.

You arrive at a junction: should you descend, loop, or continue upwards? Deciding to venture upwards, you start to notice a change in the forest. It transforms slowly with each step, fewer shrubs crowding the understory, more detritus wrapping the forest floor in a uniform blanket. And what’s that red blob moving so elegantly across the leaves? It’s a red millipede, reminding you to watch your step.

Just as you are basking in the eerily quiet like a gem anole basks in sun flecks, a sharp cackling shatters the silence. A Golden-headed Quetzal is perched high above you, barely visible. You continue into the stillness, waiting for the next encounter, into the Garden of Loneliness.

So you see, it is neither a garden nor is it lonely, but sometimes the best things in life are misnomers. That is, of course, besides Reserva Las Tangaras, which is brimming with tanagers.

A New Perspective: Listening is Learning

The soft “whit-whits” of a White-Whiskered Hermit just after sunrise. The languid stillness of an afternoon after 14 days without rain: perhaps if you can listen close enough you can hear the bromeliads wilting? The incessant calls of glassfrogs as a hidden sun slips beyond the horizon. The subtle “woos” of the Rufous Motmots closing out the daylight. Rain pelting the aluminum roof during the slim hours of the night.

These are the sounds of the reserve after one month. Sometimes you can experience them in one day, or perhaps over a week. What you can’t forget is that even with the raucous neighbors (hungry hummingbirds), the still tranquility of the forest welcomes all those who visit.

Who are we to make such claims? You would think that as biologists who both just graduated with a Master in Tropical Biology through an Erasmus Mundus program, we, the new managers here at RLT, can make a claim or two about the natural world. However, the reserve has already taught us, after only one month, the importance of listening.

My interests (Hailee) in plant phenology, agroecology, and education have taken me to mountain tops, digging through soil on farms, and into obscure parts of the world’s longest cave. The uniting factor of these experiences was the profound respect for nature I had developed as a child while traipsing through the local pond with my mom or going on a fishing expedition with my dad (it’s a surprise I’m not a herpetologist with the amount of frogs I caught as a child).

Through Jonas’s story runs a similar vein, in which he was raised by biologist parents who explored the New England hardwood forests with him and whisked him away to Guatemala as a child on insect collecting expeditions. However entrenched in the forest he was as a child, he decided to explore coastal systems as an adult, working on topics from shark senses to the impact of cryptic mud-lobsters on mangrove ecosystems.

Upon our return to a forest very unlike the ones we knew as children, it is no surprise that our diligence as learners has made us students of the cloud forest. Our first lesson that we wish to share with you: slow down and listen to the forest. You might just be in awe of the routine idiosyncrasies that the forest affords you.

Pictures 1-3: RLT Fauna and Flora (Blue-thighed Rainfrog, bromeliads, White-whiskered Hermit & Fawn-breasted Brilliant)

Pictures 4-9: Hailee and Jonas through the years

Complacency is not an option as nature continues to present itself…

After being at RLT for 4.5 months there was a fleeting thought that maybe we wouldn’t see too much new during our final month. It was more of a discussion between us to say that we didn’t think we could get complacent considering the new sightings we continued to have. We decided to record our new sightings each day for October and on all except one day, we saw not just one new ‘thing’ but often more than one! Here is our list and some photos to match.

1st ID fledgling Glossy-black Thrush and female Empress Brilliant

2nd Baby Agouti and 2 juv Green-crowned Brilliant males

3rd Heard the Ecuadorian Thrush and saw the Wattled Guan calling

4th Heard Oilbird at 5.30am circling in backyard, 2 hummers collided and landed on ground!

5th Roadside Hawk flew into the cabana front window. 6pm. Hummer feeders were on the balustrade – maybe it was trying to catch one?

6th Brown Inca hummer on Bosque

7th Golden-olive Woodpecker

8th Buff-throated Saltator singing

9th Female ACOR visiting Lek sites and checking out males

10th Torrent Ducks with 3 ducklings.

11th Hummingbirds bullying each other into the ground

12th ACOR and Toucans hanging out together

13th Tayra in river trying to climb a rock

14th 2 male and 2 female Swallow Tanagers in tree top

15th Dark-backed Wood-quail and baby

16th 4 Capuchin monkeys

17th Saddleback Caterpillar on a leaf

18th Saw the Ecuadorian Thrush singing and heard the meow call

20th Aracari close by cabana closest we have seen

21st White-whiskered Hermit being bullied by a Crowned Woodnymph into the ground

22nd Lyre-tailed Nightjar mum and bub. Female Purple Honeycreeper. Beehive in tree

23rd Fasciated Tiger-heron

24th Summer Tanager

25th Roadside Hawk swooped and took a hummingbird

27th Bay-headed Tanager sighted

28th Saw Oilbird flying circles in front of the cabana. Had only heard it before.

29th Saw a Collared Aracari chasing a Choco Toucan

31st Barred Puffbird at Lek

With not much time to go until we hand over and leave RLT, we are incredibly grateful for the opportunity to look after this unique patch of paradise. We are grateful for what Pachamama has presented to us during our time and all the amazing interactions we have had with the many species of birds, reptiles, some mammals and many insects & spiders! Coming from Australia, it was a great chance to learn about and see so many new species. It is not only the natural environment, but the visitors we have had at RLT have added to our unforgettable time here.

We are also grateful for the amazing support we have received from Dr. Becker, which only made looking after RLT even more of a pleasure.

We are off to see a few more endemic species on the Galapagos Islands before we head back to Australia, after nearly a year away.

Hasta la vista amigos.

Con amor y gratitud,

Karen y James

Spring has definitely sprung at RLT!

It is more difficult to discern clear seasons when you are so close to the equator and at slight altitude (+/-1350m). The seasons here are defined more by the amount of rainfall so it is either the wet or dry season. Given how much it rains in the ‘dry’ season here, we call it the ‘less rainy’ season. Regardless, it is definitely spring here with the number of juvenile animals and new growth we have seen. We haven’t been able to get a photo of the juvenile Agouti (sooo cute!!) but here are a few cuties…

Our visitor numbers have dropped since the northern hemisphere summer has ended and many short-term travellers have returned to their office jobs. We often have a chuckle when visitors tell us they will be back at work ‘next Monday’. It certainly makes us appreciate our lifestyle and job choices. Although we are technically volunteers, the return on our investment being here for 5.5 months far outweighs being back in office and corporate jobs!

However, we really enjoy having visitors as they allow us to share our enthusiasm and passion for this amazing piece of paradise. After 2 weeks of not seeing anyone else at the Reserve we had 3 morning Lek tours in a row, 1 guest stayed 3 nights, another 1 night and 5 day visitors. All in the space of 4 days! Here is a recent group of visitors. The group of 3 were VERY happy to find their target species during their visit. In their case, the Andean Cock of the Rock, Yellow-throated Toucan and the Golden-crowned Quetzal.

We are just heading into our final month, (already!!) at RLT and have been busy tidying everything up, waxing and varnishing walls, floors and ceilings, both inside and out, updating Guidelines, and finalizing projects. RLT will be spick and span for the next Managers to take over from us next month. The new Bird ID sheet (completed project) has been printed and laminated and already greatly appreciated by our latest visitors.

Despite not going to a ‘proper job’ each day, we do have a daily routine we follow. It naturally occurred around the daily jobs we are required to complete and has evolved to suit us (and the hummingbirds that buzz our window if we aren’t up by 6.15am each morning!). We enjoy following our natural ‘cicada’ (circadian) rhythms being up with 1st light and in bed not too long after dark! We made a little ‘Day in the Life’ video which you can watch here to see what a typical day looks like for us here at RLT.

Hasta el próximo mes!

Immersion in Nature is key

It’s one thing to visit the Reserve for a day or 2 and have an amazing experience but really it is next level to be immersed in an area for months on end. In a day or 2 you get to see just the surface which, according to many of our visitors, still ‘is the highlight of their time in Ecuador’. But when you stay longer and slow down to the pace of the forest (not including the Hummingbirds because they are adoringly manic!), you start to see, hear and feel nature. Your senses sharpen and you pick up the slightest sound or movement that usually results in seeing something different that you haven’t seen before.

This also works conversely in hearing sounds that don’t belong and are initially confusing to your senses, like a plane flying overhead or a dog barking! Yes, we had a large group of Ecuadorians who came into the Reserve, looking for the Cascades, with their 2 dogs on leashes, luckily. (We have since added a ‘No perros / dogs’ sign at the front entrance). That’s when you know your senses have sharpened to a location. We both recall the same sensation in our other 2 similar roles in Australia on the Great Barrier Reef and in the south of Tasmania.

These little movements and sounds have resulted in us spotting a variety of new (to us) wildlife. The Red Brocket Deer (Mazama americana) caught our eye on 2 occasions. Once in the coffee tree garden where it was grazing through the grass. The other sighting was in the River. He was standing in the shallows and froze when he saw James looking at him. James did his loud whistle, which tells Karen ‘grab your camera and get down here FAST!’. Knowing there will be a cool sighting, Karen obliges 😉. After standing still for quite a few minutes, the deer couldn’t hold on anymore and just squatted to do his business! Then he just casually walked across the river and continued on his day.

Another VERY cool sighting has been the Giant Antpitta (Grallaria gigantea). This was another movement-out-of-the-corner-of-your-eye moment just on dusk. Sitting at the dining table a movement caught Karen’s eye and despite racing outside to try and get a photo to identify it, it was just too far away and too dark to get a clear view. We could guess it was maybe an antpitta of some sort due to its size and hopping motion, but we needed a clear photo for an ID. You never quite know if these sightings will be a one off or a regular occurrence. Luckily, we did see this guy a few more times, but still unable to get a clear ID. Then… we were heading out for a late afternoon walk to the river and we saw the Giant Antpitta hopping on the path leading us down the hill. Karen got a nice clear photo (and some video) and we confirmed the species with Dr Becker who said it was a first for RLT.

Although it is exciting to see a ‘new’ species, it does prompt some questions as to why now? What has changed in its usual environment to make it come here?

The third very cool sighting was this beauty, a juvenile Osborne’s Lancehead (Bothrops osbornei) curled up on a pile of drying invasive species (Brazillian Red Cloak). The colour contrast was what caught James’s eye this time.

We are very curious to see what else we see as we slide into the second half of our time at RLT… Stay tuned….

This place is INCREDIBLE!!!!

Every day for the past 60+ days has surprised us with more and more beauty and wonder. If it isn’t a new bird species appearing right before our eyes, it’s a troop of Capuchin monkeys swinging past us during a Lek tour. Or, in the case of James, the river ‘providing’ another type of material he can use for something within the Reserve. Usually, it’s pieces of metal he can use for stair building but the 35m+ polypipe he found making its way down the river to become more debris is the winner so far! It won’t go to waste with James around!

The past month has been busy with visitors (30 in total for July!!) and started off with trail maintenance now that the dry(er) season has settled in. Most of our days consist of beautiful sunny mornings with clouds coming over in the afternoon and sometimes a shower in the late afternoon. We plan most of our activities for the morning for this reason. The rainy afternoons are well spent doing the hummingbird counts (4-5pm daily) as the hummers LOVE the rain! Fun fact: hummers are more active when it’s raining because they get cold easily when they are wet and have to flutter even more to stay warm, which means they have to eat more to keep their energy levels up! Ah the life of a hummer….

Karen has had fun collecting footage for her short videos on various RLT topics eg, Different shapes and sizes of leaves, Why is the Toucan’s bill so big and What is a Cloud Forest exactly? More to come, stay tuned!!

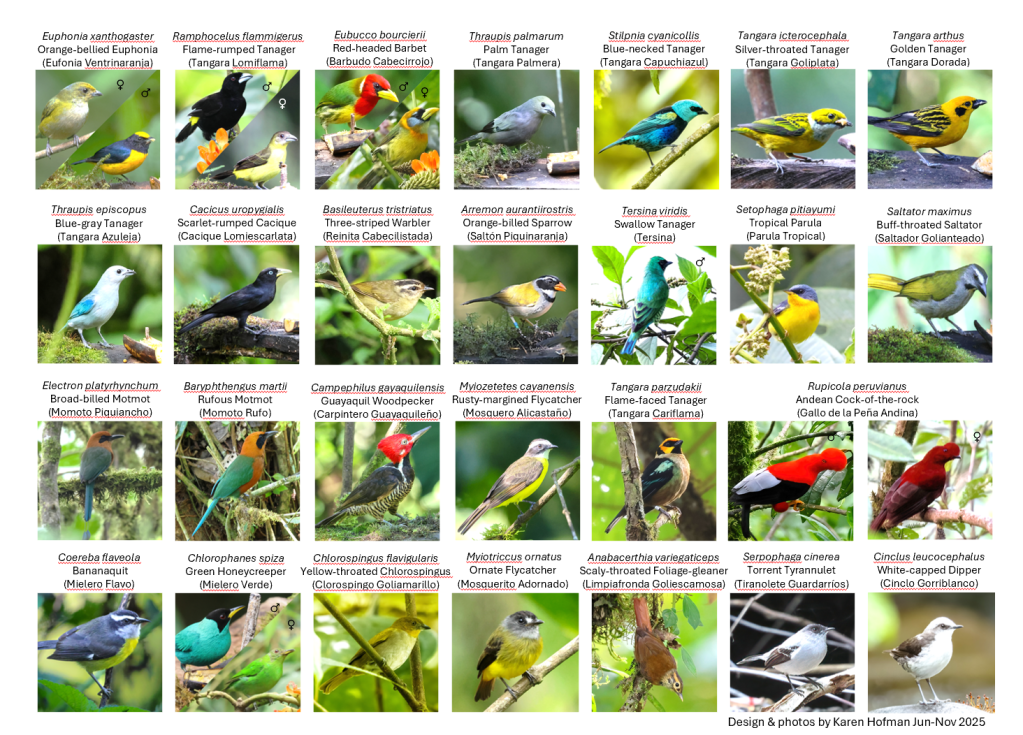

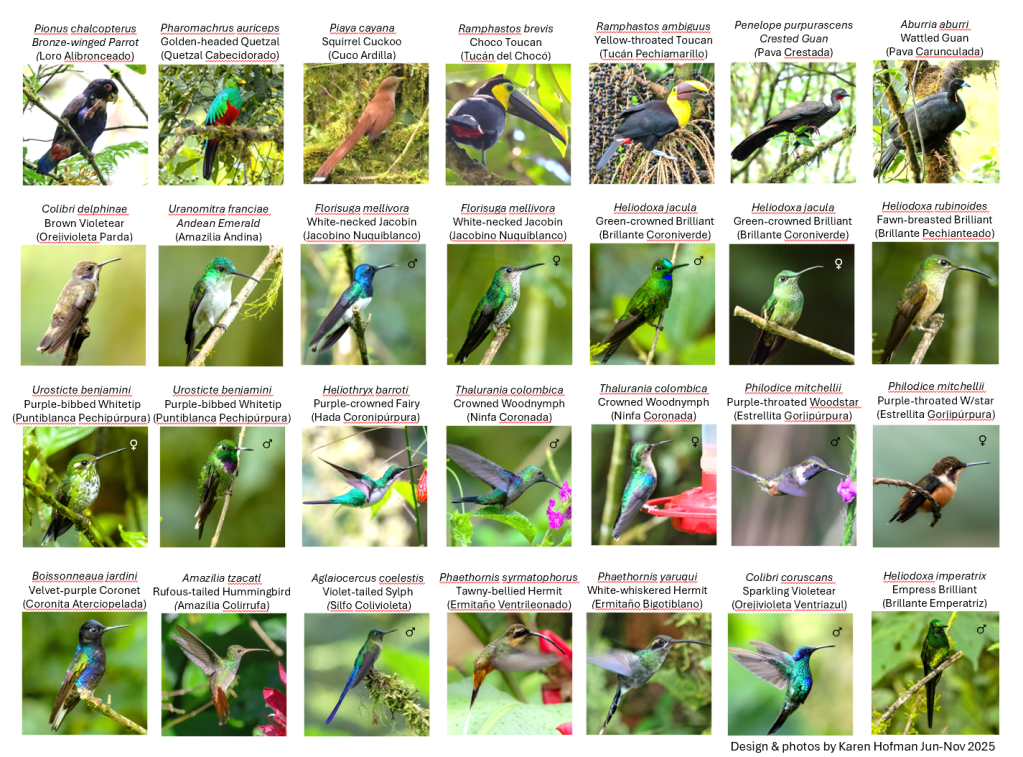

Karen has also been creating ID sheets for visitors for the ‘frequent flyers’ around the Cabana. The double-sided sheet contains 54 species. Just a mere 8th of what there is at RLT. Really, this is a great excuse to be taking photos and identifying more and more birds! At least we are both in our element and are thoroughly enjoying our time at RLT.

Upon confirming a hummingbird species with Dr Becker, she not only identified the hummingbird species but also the flower it was eating. Dr Becker noted that when she was here in January, there was hardly any of this Brazilian Red Cloak (Megaskepasma erythrochlamys) to be seen. Consequently, it has enjoyed 8 months of undetected growth and spreading! This invasive species was planted some years ago to provide more flowers for the hummingbirds. However, like many non-native species in any area, they are thriving! James dropped his track maintenance and got straight to the removal of plants and roots. Despite making bare spots in the vegetation, their removal will allow native species to resume their natural growth.

Never a dull moment for us here at RLT! (Did we mention how much we love it here?)

Karen y James

How time flies when you’re having fun!

Hola Amigos!

Crazy to think we have been at RLT for 1 month already…and what a month it has been! A huge learning curve to understand everything we can about the reserve. Obviously, it will be an ongoing process for the next 4.5 months. Learning the different bird species by sight and some only by sound has been fun as there are so many different species of bird in the reserve; over 400 in fact. We have many regulars who come in for a snack on the plantain we lay out each day and others who just flit in and out of the trees in view from the cabaña and on the trails.

Here are just a few of our regular visitors:

We have been enjoying the regular bird counts and observations. The daily hummingbird count is a little variable depending on the weather. The hummers love the rain, so they go a little wild, a bit like a young child on a sugar high, feeding, flitting and perhaps a little flirting…It has been a joy to observe the idiosyncrasies of each species.

We have undertaken a few projects including some ‘unscheduled’ with a tree falling down directly on top of the Information sign. A quick cleaned up by James and the sign is standing sturdier than before despite the extra waves in the corrugated iron roof!

We put some screens on some of the cabaña windows and the double front doors. Now we can open the windows and doors to let some extra breeze through the house as well as those beautiful sounds of nature. With upstairs being open, it certainly isn’t insect (or rat and bat) proof but we can now bring the natural surrounds a little more into the house.

Ollie, also from Australia, was a great help as our first volunteer assisting with the screens, track maintenance and signage upgrades.

We had some visitors both for the day and staying overnight. All our visitors have had a keen interest in the natural environment and have all been interesting to chat to over a cuppa and freshly baked biscuits. The younger generation we have had here particularly enjoyed the off-grid experience and asked many questions about our nomadic lifestyle. We enjoy the unintentional inspiration they derive from their visit and the conversations we have.

A major source of enjoyment for James here (and in other similar roles we have had) is engineering in a practical sense. A great example is this trolley James made to transport the gas bottles, one at a time, to and from the road (2km) outside our property. Despite being a little rickety with wooden wheels, she works a treat!

Be sure to follow RLT on the socials for daily updates and of course photos and videos of the beauty that is Reserva las Tangaras.

Karen and James

Bienvenidos James Y Karen!

Hola Amigos!

Finally, we arrived at Reserva las Tangaras after knowing for close to a year that we would be the Jun-Nov 2025 stewards. We are Karen & James from Australia!

We took the long way around to get here departing Australia early January. We spent two months in Europe visiting family and friends in Spain and Holland. We road tripped through France, spent a week in the UK and flew to Bolivia where we travelled and volunteered for 3 months. After a week in Peru, we headed north to Ecuador. Although, what was meant to take 2 flights from Cusco, in one day to arrive in Quito, it ended up being 3 flights over 3 days! Ecuador have recently made it mandatory to show your Yellow Fever vaccination at check in. The check-in person in Cusco forgot to mention that to us. Unfortunately, Karen’s card was packed in our checked luggage. We were offloaded in Lima and tried again the next day. After purchasing a new flight (now via Bogota) we stayed overnight in Lima. The flight from Lima was delayed and we missed the connection to Quito. Another overnight required, this time in Bogota. At this point some might say it was a bad omen and maybe we shouldn’t be going. Not us!! We finally arrived in Quito in the morning of the 3rd day, got a taxi to Mindo and arrived at midday. We found Danielle and Joshua, the outgoing stewards and after a bit of shopping, lunch and some meet and greets we headed out to the reserve.

Oh My Goodness! This place is incredible!! The beauty of the forest, the mountains, and the wildlife is mind-blowing. We knew it would be amazing here but just how amazing has far, far exceeded our expectations. To make it even better, the state of the house, the immediate surrounds and beyond have been left in such great condition by Danielle and Joshua, that our transition to taking over the stewardship role has been as smooth as a toucan’s beak.

We can’t thank those guys enough for the work and consistent effort they have put into the upkeep of the Reserve and its facilities to make our transition so easy. We know it wasn’t an easy road for them but they have done wonders. Thank you both (and Parker of course!) for everything and your commitment and dedication to RLT the past six months!

So, who are we? James is a qualified Civil Engineer with a background in construction prior to his engineering days. Karen has a background in tourism and education and has a PhD in conservation and behaviour change. But, we left our corporate jobs in 2019, opting for a more relaxed nomadic lifestyle. We have been able to use our combined skills to undertake similar jobs to this stewardship role on the Low Isles in the Great Barrier Reef and the most southern island on the Australian continental shelf, Maatsuyker Island. It works best for us in these roles to split the jobs so, in brief, James will look after the systems, facilities and tracks and Karen will showcase her tour guiding skills with visitors and take charge of the bird counts and admin.

We hope you follow our journey with us via a monthly blog here and regular social media posts on Facebook and Instagram. After just a few days Karen has enough photos for posts for a couple of weeks already! Sign up and stay tuned for our adventures in this most beautiful location, Reserva las Tangaras. Or, come and visit for a day or more as a guest or a volunteer.

Nests, More Nests, a “Graduation” & a Mother’s Note

We have been seeing a lot of nests around the Reserve in May. It began in late-April with a Silver-Throated Tanager nest. Though they have since fledged, we still see the family of 4 around the cabaña plantain feeders each day.

We have so many different styles of nests throughout 2025:

- Hummingbird nests with small, soft materials including some colorful flowers

- Andean Solitaire nests built into an earthen wall

- *Orange-Billed Sparrow nest built on the ground with a roof made of sticks to cover it & make it inconspicuous

- *Thick Billed Euphonia nest built so high we can’t monitor it’s progress, but we can see the “parents” flying in and out throughout the day

- *Slaty Spinetail nest built into an orb of sticks that you cannot see into

- *Yellow Throated Chlorospingus nest is made of moss and uses the naturally growing foliage and moss as a part of the nest

- Silver Throated Tanager nest covered by moss and fiercely guarded by the “parents”

- *Red Faced Spinetail nest is inside of foliage that is hanging from a branch in a tree

*indicates currently active nests

Though we would love to share pictures of every nest, we are trying to keep our distance to ensure the nests have the best chance at success. However, we are actively documenting the progress of each nest at the Reserve with our other science data. If you’re planning a visit in the next 3 weeks, we will happily point them out to you from the cabaña!

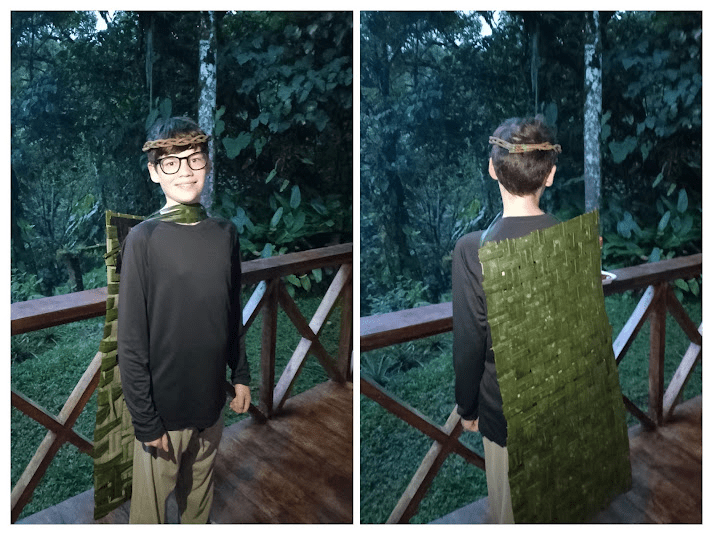

A “Graduation”

May brought the close of homeschooling for our resident 5th grader, Parker. Parker will move on to 6th grade in August which is the start of “Middle School” where we live. We conducted a fun “graduation” ceremony for him where he got to parade around the house to a graduation song of his choosing. Joshua made him a cap and gown and Danielle conducted the ceremony and gave a speech.

We wanted to get a final interview from Parker to get his thoughts!

How has your experience been at RLT?

Great. There were sometimes where I wanted to leave and didn’t want us to be on the job. After a while, I kind of grew into this place and I will miss it forever, to be honest.

What is your favorite thing about RLT?

Nature, the birds. There are a variety of birds and doing outside work sometimes was fun and sometimes was annoying. I got to see some cool birds and some enormous birds like the Crested Guan, which is my favorite. We got to see some mammals like the Central American Agouti and Nine-Banded Armadillo in the yard!

What is your least favorite thing about RLT?

No internet!!! (he asked for 3 exclamation marks in particular) It is nice because it forces you to look outside but sometimes, I wonder stuff or have questions and have to wait until we go to town to look it up.

What was your favorite part about homeschool at RLT?

There were less classes and after school, if it wasn’t science, I could just chill.

What was your least favorite part about homeschool at RLT?

Math.

What was your favorite subject in school this year?

Reading and Writing. Plus, a little bit of science.

What are you looking forward to in 6th grade?

Not being overwhelmed by the people and to be an average student.

What are you looking forward to when you get back to Utah?

Internet, being able to flush toilet paper, good showers, other people I can talk to that aren’t just my mom and Joshua isolated together.

Any Final Thoughts?

I have found my love for a lot more animals here at Reserva Las Tangaras. My favorite animal was the Nine-Banded Armadillo but now is the Central American Agouti “It’s so cute OMG”. I didn’t really have a favorite bird before but now it’s the Andean Cock-of-the-Rock. It is so cute; it looks like an alive stuffed animal.

I enjoyed just waking up and seeing the sunshine on the leaves and hearing the birds chirping. You don’t know what you’re going to see that day. Every day is magical here.

A Mother’s Note

Happy Mother’s Day! I wanted to take a moment to note my experience as a mother with a child at Reserva Las Tangaras.

Thinking back, Joshua & I were worried that since we had a child that would need to accompany us, we wouldn’t be eligible for this once in a lifetime opportunity. Dr. Becker was excited to hear we would be accompanied by an 11-year-old, and we were able to let out a sigh of relief. When I was 10/11 years old, I never would have imagined an opportunity like this. At that age, I recall being a great big ball of confusion and emotions (OH THE EMOTIONS). This was an amazing opportunity for us as a family.

Before coming to RLT, I was a hard-working mom navigating the world and trying to create a great life for Parker. My personality-type centering around ambition and perfectionism, I didn’t realize that I was actively missing out on Parker’s life. I was overworked and exhausted. Proposing movie and pizza nights instead of building Lego or drawing comics. I was a tired, overstimulated ball of stress.

For nearly 5 months now, the 3 of us have been spending a lot of quality time together, learning together, exploring together and acclimating together. Adjusting to a remote lifestyle after a lifetime of living in the city has been incredibly enlightening, to say the least.

Now that I have had time to slow down, I realize what I’ve been missing, but most importantly I realize what I’ve been present for since we arrived in Ecuador on 31 December. I have been able to watch my little boy grow into an adolescent. He has gotten taller, his face has taken shape and he exudes happiness daily. The best part was that I got to watch it all happen, I got to watch every moment. Thinking about what comes next: friendships, first love, new hobbies, High School, planning for adulthood, etc. I am so grateful to have been able to intentionally slow things down at this stage of his life and realize it’s importance, so I don’t miss out anymore. It is important, it’s not just a part of life.

My most prized takeaway from this experience is remembering what is most important to me, what truly brings me joy: my little family. We now know we can live on an ultra-tight budget, we can hike miles to get to the nearest services, we can tolerate only seeing/talking to each other for up to 2 weeks, we can help each other through different struggles, we can have the difficult and awkward conversations, we can learn new skills together and much much more. We can do all of this AND wake up happy every day. No busy city life, constant stimuli or job can take that away from us now.