Plants upon plants upon plants

There are a couple of reasons that cloud forests can look so magical; one being the daily mid-afternoon mist rolling in to settle heavily upon the mountains so that you often find that you are wandering through the clouds on your way home for dinner, another being the strangely primeval-appearing flora; crowds of epiphytic orchids, bromeliads, ferns, mosses and lycopods who have casually draped themselves over what appears to be any available surface, be it tree trunk, crown or yourself, if you were to stand still for long enough.

Epiphytes are found in every major group of the plant kingdom, with the most commonly known species being orchids and bromeliads, as those of you with a penchant for easily maintained houseplants will likely be very familiar with. The word ‘Epiphyte’ is derived from the Greek Epi ‘Upon’ and Phyton ‘Plant’. They are aerial dwellers who firmly entangle their roots on branches or trunks of other plants, capturing water and nutrient-rich soil blown into the canopy to aid their survival.They may sound parasitic as they ‘use’ other plants as a physical support on which to grow, however in a lot of cases they can indirectly benefit their host, rarely impacting them negatively. In fact, over time the accumulated organic mass captured by the epiphytic roots can become dense, allowing fungi called ‘Mycorrhizae’ to populate their newly fashioned soil terrace. This may be for another lengthier blog post but ultimately the mycorrhizae fungi majorly aid in the uptake of scarce minerals and can be of huge importance to many trees and their forests globally.

The aforementioned soil terraces cocooned in the epiphytic roots not only aid the trees, but also provide a safe haven for many animals, such as squirrels and hummingbirds. Additionally, as epiphytes need their own water source – being too far from the soil to extract it in the ‘usual’ plant method – they can be quite ingenious with their solutions, once again indirectly benefitting a whole host of creatures. For example, some bromeliads have evolved to arrange their leaves to capture water and detritus material in a cuplike vessel, which creates an aquatic habitat allowing tree frogs, snails, flat-worms, mosquitoes, salamanders, and even crabs to complete their life cycles ‘aerially’.

For instance, there is a tree directly opposite the Reserva Las Tangaras cabin’s back porch which is so laden with hangers-on that it’s incredibly difficult to identify where the epiphytes end and the tree begins. A quick root around in some of the leaves and I find some vivacious dragonfly larvae, two different species of tree frogs, a number of grasshoppers and crickets who had likely spent their nymph-phase here, not to mention the dreaded thousands of mosquito larvae thoroughly enjoying the nooks & crevices of this crafted aquatic habitat.

In Europe, we don’t have any of these typical ‘tropical’ epiphytic rooted flora to gaup at and scrabble around looking for frogs in, but what we have a lot of, especially where Jack & I are from (the UK) are mosses and lichen. Much less striking but equally as fascinating in what they can do. They are so seemingly inconsequential, yet they cover just about everything in the small villages tucked into Northern England. The structures in these settlements are largely made up of different varieties of stone, which moss & lichen are particularly attracted to in the damper climates. They like to cling, not only onto our local pub’s outside wall, but to all vegetation surrounding us here in the cloud forest too.

Mosses & liverworts appear under the family Bryophytes however their true extent (both diversity and magnitude) is unknown. Much of their biomass is concentrated in the canopies of trees so as such their species diversity is rarely included in forest inventories, having primarily relied on tree falls to obtain such knowledge in the past.

As you climb higher and higher into the cloud forest the appearances of bryophytes increases with your ascent. Perhaps this indicates that they play an integral role in this environment, you wonder. You thought correct! They are infinitely useful within this habitat. One of their main capabilities being to retain water. Their water holding capacity can actually exceed total annual rainfall by 50-90%, the additional moisture derived from fog that settles upon the slopes. This function is especially important for areas that vary more in their seasons (such as the sub-alpine cloud forest at more than 3500 metres above sea level) because the mosses slowly release their harboured moisture to the forest floor and surrounding vegetation during the drier periods.

Now, you may have been here in the wet season but for those of you who haven’t, the wet season is WET. We have actually had 114mm of rain, in a single day! It is difficult to imagine 50-90% more water within the environment, but if one day all the mosses all just got up and said ‘adios’, there’d be a colossal increase in landslides and unstable ground. Not to mention, flooding would become substantial on the heavier rain days and the Reserva Las Tangaras bridge would almost certainly be wiped out. We’d be trapped, albeit happily.

Now we all have a deep newfound respect for epiphytes, here’s the sad truth – deforestation of the lowland forests surrounding the cloud forest is predicted to lead to large reductions in cloud generation. This would lead to an irreversible loss of the epiphytes that rely on these hydrological systems. Subsequently, due to the classic ‘snowballing’ ecological effect – that which we have come to know too well in this era – much of the ecosystem in these magical areas will be damagingly impacted with the loss of the epiphytes. Unfortunately, epiphytes play a hugely vital role here not only helping to define the cloud forest but by preventing erosion and landslides, managing flood control, releasing precipitation, sheltering hundreds of species of animals throughout their life cycles, looking beautiful at dawn with glistening dew, adding to the carbon cycle, capturing essential vitamins for the trees they reside on, and much more. So, the next time someone comes up to you and tells you that they’re about to deforest an area adjacent to a cloud forest you can scream ‘But the EpiPHytES!!’ in their face and immediately bombard them with all of this interesting information and they’ll maybe think twice.

(And yes, epiphytes can also harbour their own epiphytes, adding just another dimension to the biodiversity of these lush cloud forests.)

Learning to Live in & Listen to the Forest

Hello everyone, Katie and Nick here again with a blog post for April 2021 🙂

Hard to believe our time here at Reserva las Tangaras is almost over and what an incredible journey it has been. As we are getting ready to say goodbye to this amazing place, we wanted to reflect on some of what we have learned while we were here…not from books, or teachers, or from previous managers, but from the life in the cloud forest.

Living this lifestyle can offer so much to the average, modern-day, management couple or visitor in general. Many people come here to Reserva las Tangaras already having decided they wish to live their lives in a more circular way with nature, rather than linear, but how many of them know how to learn from the forest? How many people truly know how to sit and listen to what mother nature has to say? and What IS living in a linear economy or a linear way versus living in a circular economy or circular way?

Usually, even those of us who arrive here as environmentally conscious individuals live a typical busy life that is socially acceptable in the first world. Many of us are are lucky enough to grow up a relatively “normal” life and receive an education along the way, then we either get a job or perhaps further our education, then we work on climbing the promotional ladder and getting that perfect job, usually accumulating a car or a house or many belongings along the way, while also typically adopting a pet or two and a eventually having a spouse or a family as well. Many of us chose to live either in a city or close enough to a city, that we can commute back and forth efficiently enough to do our jobs well and still have time to spend with our pets, spouse, and family. As an environmentally conscious person, living a socially acceptable life in the first world, likely we would be buying products with as little plastic packaging as possible, recycling when available, choosing to be a vegetarian or vegan, working a job that benefits the natural world in some way (Teacher, scientist, naturalist, etc.), and perhaps even driving a small-economic car or riding a bicycle for transportation. These are all GREAT things that each of us can do in our own small ways to help mother nature, and in fact it is far more than the average person in most first world countries are doing for the environment. So, if this is you, be proud. But, can you do more? Yes. We ALL can do more. And as people who are perhaps more informed about the environmental issues of the world today, it is our responsibility to do more and to be better environmental stewards tomorrow, than we were today. This means not only taking action in your own life, but also sharing your knowledge with others who may not know where to start. All of this can be a lot…can be a bit overwhelming at times. Sometimes, we also need a break. The stresses, the worries, the fast-paced lifestyle, the social and societal pressures, the temptations, the easy-escapes…sometimes those of us living with what we think are the closest relationships to nature, are actually the farthest away. This place, Reserva las Tangaras, and one would assume other places like it, offer a reset. A place to rediscover our passions and remember what drives us to be the best environmental stewards we can be…

Let’s say you have made the commitment to spending some time in a place like this. You needed a restart. A natural reset. You decided that living an off-the-grid lifestyle in a wildly foreign environment would help to re-ignite your passions for the natural world. Good for you. Get ready for a wild ride 😉 You will experience all of the ups and downs of this amazing adventure, hopefully learning from each experience along the way…therefore, there are no negative experiences, only lessons. Besides the lessons that you may encounter mentally and emotionally, there will be many experiences that test you physically and spiritually. For the remainder of this blog, we are going to focus on some of the lessons that we have learned strictly from the natural environment…from the cloud forests of Pichincha.

Let’s start with the basics, orientation. Do you know where you are? If not, how do you figure that out? Well, follow the sun. We all know that the sun rises more or less directly East and sets more or less directly West. Once you know which directions are East and West, you can deduce which directions are North and South. Assign landmarks to those directions, ex. You notice that when you are at the ACOR lek, the sun is directly behind you, therefore the ridge you are on is to the East of the cabin. Continue assigning directions and locations to various landmarks around the reserve, which you can see or figure out their location, from several different vantage points. Now over the next days, weeks, and months, keep paying attention to where the sun is at various locations around the reserve at many different times of day. Pretty soon you will be able to tell what time it is, just by looking at the position of the sun in the sky. You will also be able to tell approximately where you are on the reserve property. This is a pretty basic orientation skill, but one that can also be very useful.

How about the river, have you ever truly watched what the river is doing? Enough to let it speak to you about what is going on in nature around you? Again, starting with the basics…which direction is it flowing? Does it always flow that direction? Likely here in the Andes Mountains, it is always flowing in the same direction…down the mountain. What color is the river? If it is relatively clear, then there is little sediment in the clean water, meaning there has been little to no rainfall lately. If the river is cloudy and brown with lots of debris in it, it’s likely there has been heavy rainfall recently or upriver from the section of river you are looking at. Now, how high is the river? Look to the riverbanks for any trees or shrubs that standout as an easy landmark, then look to the boulders on the riverbed. If you don’t notice anything out of place, then perhaps the river is running at its normal height; But, if you notice darky muddy marks along the riverbank and you can see a clear line of moss/algae growth on the boulders on the riverbed, then likely the river is running lower than its normal height. If you can’t see any of these high-water marks and you notice that many of the boulders on the riverbed are actually moving along the bottom, then likely the river is running higher than normal. Are there any birds on or around the river? If so, then likely the river is running at a fairly continuous velocity and at a relatively normal height. That means the river at the moment is stable enough that fish can be seen for feeding, bugs can skip across the surface for insectivores to eat, and spiders can build their webs. If there are no birds or riparian forest species of any kind in sight, then the river could be ramping up to become more unstable. These are all good signs to watch out for, especially if you are working IN the river. I was always told to stay clear of the river when it’s raining, but here in the cloud forest flash floods happen quickly and occasionally on a sunny day. After all, you never know, it could be raining at the top of the mountain for one hour or more before it reaches you.

Now let’s talk about the BIRDS! You must have some love of birds if you are coming to live in a place like Reserva las Tangaras, it IS the Tanager Reserve after all! So besides identifying them for your life’s ebird list, do you know what else these beautiful little creatures can tell you about your environment? A lot!

For starters, most birds have many different types of songs or calls, but many have a specific “alarm” call that they sound when danger is near. If you hear a loud, shrill, or very blunt call in the forest, this may be an alarm call. Look around for a potential bird predator, perhaps there is an eagle soaring above, or a jungle cat walking the trails below, or maybe they are calling about you! Either way listening out for this “alarm” call can point us in the direction of potential bird danger and therefore something else incredible for us to see in the cloud forest.

Have you felt a strong, cool wind and looked up to see a flock of birds just soaring over you? More than likely those birds are riding the thermocline (a distinct change in temperature, in this case leading to two air pockets of different densities) layer in the air being pushed forward by an oncoming storm. Birds riding this thermocline layer, can often signal that a storm is close by and it may be time for you to take cover! Usually, this sighting is coupled with a cool breeze, or an increase in bird calls, or an overall increase in overall animal movement to take cover in protection of the storm.

And finally, they can teach you to truly live in the moment. As Nick wrote in his last blog, the birds live their life to the minute. They wake up, and are only ever concerned with the basics: food, calling for a mate, more food, mating, probably more food, and perhaps building a nest all while on the constant look out for predators. They wake up and go to bed with the natural light of the day, they dry their wings and bask in the heat of the sun, and enjoy a cool bath in the rain. They bounce around in the fruits and flowers of the trees when they are abundant and supplement their diet with bugs rich in protein and fats when things are not in bloom. Birds travel incredible distances to find the perfect mate or the perfect meal and many don’t leave their home area once they have found the perfect spot. They are beautiful creatures that just exist and BE in nature…which we think can teach us humans quite a lot.

We have learned so much from living in the cloud forest for 6 months, yet we know there is still a lot to learn. We hope to be able to return to this incredible place again one day and see what the birds can teach us that time…now go out there and see what your forest, or garden, or stream, or lakeside terrace can teach you! We bet that if you take the time to sit, observe, and just BE…you will be surprised 😉

Thanks for reading! We hope you’ve enjoyed! All our best, Katie and Nick

Pocket Monsters

In the early 2000’s, my wife Katie, went through her Harry Potter phase and two thousand miles away my sister was being hypnotized by boy-bands. In the same house, I had just had my treasured card collection stolen, ending my obsession for Pokémon. Pokémon are a media franchise created in 1995 by Satoshi Tajiri, which features a host of fictional “pocket monsters” which users can capture, collect, and battle with each other. I had the Pokémon playing cards, I had the Pokémon Gameboy games and I watched the Pokémon animes. I was lost in the magical world of Ash, a young Pokémon collector who visits far-flung locales in search of Pokémon, helping his friends and battling his foes along the way. I would scrutinize each Pokémon’s abilities and artwork while combing over my rolodex of caught Pokémon in my Pokédex. I would pump my chubby fists in victory when my Pokéball finally closed over the hyper-rare Pokémon I had been searching for.

The endorphin rush from capturing “Lapras” for the first time has only ever been mirrored for me in bird watching. When a rare bird I thought I would never see blesses me with a short visit, I still fist pump the moment the bird flies away (after deciding it has had enough of me staring at it). I would assume that the creator of Pokémon is a birder, as they have captured, as in birding, the thrill of seeing something not often witnessed. Unbeknownst to the creators of Pokémon in 1995, some of the details of the Pokémon universe have been weaved into modern birding life, so much so that I continue to harken on that modern casual birding is just like Pokémon.

Pokémon range from grass loving bug-type Pokémon, Pokémon only found in shore and open water environments and a variety of specialists thriving in the eco-niches of the Pokémon world. Here at the reserve, we have been encouraging bamboo to grow around the property and at the same time seeing several bird species that are linked to stands of bamboo. A walk up towards an old finca on a nearby trail reveals a few different species of seed-eaters, which you will not find if you are only looking in the dense forest. The variety of colors, shapes, calls, and behaviors in the bird world is astounding, while some birds boast amazing abilities such as the Club-Winged Manakin who plays its wings like an instrument. Sure, no bird can breathe fire, emit poison gas, or fire electricity from its wing tips, but my point is that the bird world holds my wonder on an even grander scale than Pokémon did, yet the feeling is the same as every time a new set of Pokémon characters were unveiled.

Modern birding sees heavy use of eBird, a bird checklist app which is helping to monitor global avian population dynamics by asking users to submit observations of birds that they see around the world. More than 20 years after it was imagined in Pokémon, the modern birder can now carry their own Pokédex with them in the form of a cell phone loaded with eBird. We can check which species need to be filled on our next excursion and see which birds we are likely to find in certain areas. Unlike in Pokémon, the birds we observe in the real world are not used as pawns to battle out a war between human ideologies, however, the “hotspots” on eBird – areas, such as the Reserve, where birding is excellent or popular – make the quest to have your name as the “final boss” (number 1 on the top 10 list for the hotspot) an ever-present drive. Pokémon Gyms are a place where Pokémon trainers can pit their Pokémon against top resident trainers for fodder in more elite clubs or as a measure of an up-and-coming trainer’s progression in more beginner clubs. I like to dedicate at least 1 hour to birding per day and, on big days, I tap out at about 6 hours of birding per day. My quest to be the “final boss” of the reserve ends in the next few weeks and I am happy leaving the reserve after scratching my name on the scoreboard. The scoreboard of the big “gym”, Pichincha, Ecuador, however, requires years of dedication to get into the top ten. At just under the size of Texas, yet having around 500 more species than the entire United States of America, Ecuador packs a ton of diversity and abundance into one small area. The competition around here is fierce and uncrackable to those, like me, who are lucky enough to only visit for a while, before being ejected from the gym due to bringing in lame Pokémon.

Though Ecuador may be the best place to visit to really rack up your life list, it is not the first or last place that I have explored for birds. Mr. Peter Davey, the “final boss” of the Cayman Islands, told me when I first started birding that eventually I would get to the point that I would base my travels on what birds I would likely see in a country. I gave him a disbelieving stare back as an answer, yet here I find myself thousands of miles away from home looking for inconspicuous Antbirds. Much thanks and apologies to my loving wife who puts up with my adolescent like obsession with birding. We hope to move on after our experience at Reserva Las Tangaras to countries who may not host such a vast number of species as Ecuador, but who’s menagerie of offerings dazzle us just the same. You can beat a Pokémon game on Gameboy in a month or less, but the world of birds in unconquerable as the combination of precise GPS coordinates and timing are out of reach for most budget travelers such as ourselves. But just as with all high scores, the fun is in getting as close as possible to your goal.

Humble birders will understand that their place is to be the mediocre species guffawing at a bird the moment it relieves itself in front of the observer, mid-way through its mind-boggling unassisted migration between continents. I am a satisfied with my place in this agreement, but some of my reasons to collect as many birds as possible lies in my suspicions that environmentally we are in the end of days. As in the Pokémon world, the natural world has its villains: mining, logging, oil fields and, according to Paul Smith’s College, an acre-of-untouched-Amazon-rainforest-cleared-per-SECOND scale animal agriculture industry, all of whom seem mighty keen on destroying our natural world as thanks for our continued patronage. Ash’s tale is weaved with battles between his Pokémon and “Team Rocket”, one of the villains of Pokémon, whose catch phrase “surrender now or prepare to fight!” is rather fitting for the times we live in. We should only be passive observers, interacting with birds on a mutual timeline, but now the need for our own heroic Ash figure is ever increasing with the rise of environmental threats to bird species around the world. Birders who do not join in the battle between good and evil will be satisfied to know that their grand children will not see the same wonders they have seen if our human path stays the same.

Where the creators of Pokémon went wrong was to anthropomorphize the characters a bit too much. Birds are victims of humanity’s greed, yet they are not expected to understand why a bulldozer is tearing down their habitat to make pastures for cows or why our decades of garbage are littering the stomachs of seabirds. All they know is all they have known, to wake up and survive. Every trait, every color, every decision serves a purpose, yet they may not need or have any purpose themselves and just exist. To be, rather to be someone or be something, is a valuable lesson that birds have shown me. They do not seem to be thinking about yesterday, they are instead focused on eating or preening in totality. They do everything the best they can as their life balances on the knife edge of survival. This encompasses my quest to “catch ‘em all” – so I can be there in person when the birds decide to teach me a lesson on how to be a better human being.

Our Customers: The Hummingbirds at Reserva las Tangaras

Hello again everyone! Katie and Nick here, welcoming you to our third Reserva las Tangaras (RLT) blog post. We hope that you pour a cup of something delicious and enjoy this month’s entry!

Many of you faithful RLT blog readers will know, as managers of the reserve we not only care for the property, engage with locals and tourists who visit us, but we also conduct a variety of long-term avian based research projects. One of the most popular of these research projects is a daily hummingbird survey. A photo of a female White-whiskered Hermit (Phaethornis hispidus) visiting one of the RLT feeders is below.

Every day since January 2014 (that’s over 7 years of data at this point!), the managers of RLT have conducted a one-hour long survey of the hummingbirds who visit our feeders. There must be three feeders out during the survey and each feeder must be filled with the exact same sugar solution of 1 part sugar to 4 parts water. If you think this seems silly, that hummingbirds will drink sugar water no matter the solution…tell that to Alaine Camfield, in his 2003 paper “Quality of Food Source Affects Female Visitation and Display Rates of Male Broad-tailed Hummingbirds”. This paper is available in the below references if you are interested, but evidently the 25% sugar solution MATTERS to the hummingbirds. So anyway, data collected includes hummingbird species, number of individuals, the number of individuals of each gender within sexually dimorphic (meaning, species where the male and female can be identified based upon their plumage, size, or other outward characteristics) species, and anything else that may be of note. Other observations that may be noteworthy include behaviors observed (ex. mating, aggression between birds, preening, etc.), if a bird has an identification band on its leg (as seen in the photo below of a female, Green-crowned Brilliant), or if a bird has a key identifying characteristic (ex. Missing a leg, broken wing, abnormal growth, etc.). As you can imagine, this has produced quite the dataset over the years with a plethora of information.

But, we keep asking ourselves the same question day after day…why? Why are we doing this survey? What is the point? What is the collection of this data telling us? Why is it important that we do this? We’ve been here for three months collecting this data Every. Single. Day. And for what purpose? So, we did a little research and decided to look into it a bit further…

Firstly, why are we doing this survey? What is the point?

Well, at its most basic level. We are conducting these daily surveys to obtain a population estimate of the hummingbirds which visit feeders in this area. By noting all the various species, counting the number of individuals, and monitoring banded individuals; we are collecting information on the general hummingbird population local to this area (a neo-tropical, montane cloud-forest with a study area at an altitude of 1350m in secondary forest, boarding riparian and primary forest) during all times of day across the wet and dry seasons (there are technically only two seasons here, not four as in temperate environments). Also, as we are a nature reserve since 2005, our study can be replicated in an unprotected area for better comparison as to the importance of nature preservation and its positive effects on the overall health of the ecosystem, but specifically on hummingbirds. This means that due to observed trends over time, we have a fact-based estimate of what species we will see in this environment during any time of year. This can be important information for presentation to government or political officials in the argument against deforestation, planned destruction of natural habitat, or the excessive growth of “eco-tourism” operations near or in protected areas. For example, don’t clear that 2 hectares of primary forest to build an “eco-lodge” because there is a high local population of the rare, Purple-bibbed Whitetip (Urosticte ruficrissa), which thrives in montane forest undergrowth and may be lost if its habitat is destroyed. Do we have proof of how exactly this habitat loss affects hummingbirds? You bet we do! Check out Hadley et al. 2018 (full citation available below in references) for “Forest fragmentation and loss reduce richness, availability, and specialization in tropical hummingbird communities”. Below is a photo of the Purple-bibbed Whitetip male, as they happen to be one of the more prevalent species to visit our feeders, despite their rare status in Ecuador and globally. They could be one of the more vulnerable species to anthropogenic impacts such as deforestation and habitat loss.

Secondly, what is this data telling us?

Well, when we sit down and truly look at the data…it can tell us a lot! One thing we have learned according to observations over the last 7 years is that we see a lot of mating behavior between February – May, resulting in lots of juvenile or sub-adult hummingbirds being seen at the feeders in July – October. Mating behavior can be described as active male on male aggression, interspecies aggression, or mating attempts made at the feeder (female sitting on feeder and male approaching from behind), or actual copulations seen (rare!). Juvenile or sub-adult hummingbirds are identified due to their plumage, which may still contain all or most of their post-hatching down feathers. They can also be identified due to their overall body size, bill length, tail length, or wing development.

One interesting study published in a 2018 edition of Plos ONE, highlighted the use of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology to characterize hummingbird visitations at feeders to help elucidate behaviors, clarify population dynamics, and define community structure. Essentially, asking very similar questions related to hummingbird species richness and behavior to our own here at RLT, but in an urban setting…pretty much the opposite of our own. Read more on this in the open journal article Bandivadekar et al. 2018.

Another lesson which is easy to learn, is how the overall populations of each species seem to be fairing over time. For example, according to the data over the past 7 years a few species have consistently had the largest number of individuals coming to the feeders, 1) the Green-crowned Woodnymph (Thalurania colombica), followed by 2) the Andean Emerald (Amazilia franciae), and the 3) White-necked Jacobin (Florisuga ellivora); so, we can assume that those species have a healthy local population. Some species have shown extreme variability in their numbers coming to the feeder, sometimes having very high numbers (healthy local population) and sometimes having very low numbers (unhealthy local population), such as: the Fawn-breasted Brilliant (Heliodoxa rubinoides), the White-tailed Hillstar (Urochroa bougueri), the Brown Violetear (Colibri delphinae), and the Brown Inca (Coeligena wilsoni). These are species that scientists could ask several questions over. Why are they rare during some months and abundant during others? Why during some survey days are they present in high numbers, but on other survey days they are not observed at all? What environmental factors are changing their population density at the feeders? Is it an anthropogenic (human-induced) factor changing their population density at the feeders? Then there are those rare beauties, which are always a rare sight no matter the time of day or the season, such as: the Green-fronted Lancebill (Doryfera ludovicae), the Purple-crowned Fairy (Heliothryx barroti), and the Little Woodstar (Chaetocercus bombus). Does this mean that their populations are locally unhealthy? Or are they perhaps a rare or vulnerable species nationwide or even globally? One scientifically acceptable method that RLT uses in answering some of the above questions regarding hummingbird population health, is that of banding and recording recaptured individuals. By hall-trapping (a method of low-stress, hummingbird capture) birds and collecting basic data on them (weight, age, plumage, brood-patch presence, or absence, etc.), then fitting them with a small identification leg band, we can then continue data collection on that individual over time through recapture and data collection techniques. We can learn how long the individual bird lives, if and when they reach sexual maturity, during which season they develop the most fatty tissue, if they are migratory or year-round settlers, if they produce young, etc. Only results from a long-term data set with recapture capability can teach us these lessons. Studies with results like this can be seen across a variety of hummingbird species, one such example being in Calder et al. 1983 highlighting the Broad-tailed Hummingbird (a U.S.A based species) listed below in the references. You can also read a bit more about this in RLT’s Field Reports from the last 5 years of Bird Banding Expeditions organized by Life Net Nature (LNN): https://lifenetnature.org/

Thirdly, why is it important that we do this? Why does it matter if we do or do not conduct these daily surveys?

Well, it matters for several reasons. One being that a healthy population of hummingbirds in this area determines a healthy density of native and endemic flora. We all know that bees are important pollinators, but did you know that hummingbirds are as well? They are proven to be a key vector in direct pollen transfer, with native and endemic hummingbirds preferring (thanks to evolution!) native and endemic species of plants. The more we know and understand our key hummingbird characters, the more likely we are to know and understand the important flora of this area as well. This is something that may seem fairly obvious, but most of us grow up learning about the bees…not necessarily the birds. If this interests you (as it did me), check out these open and free journal articles on the subject, all referenced below: Feinsinger et al. 1986, Jimenez et al. 2012, and Ornelas et al. 2004.

Another important reason for conducting these surveys, is that there is still SO much we still do not know about some of these species from a basic life ecology level. In a paper from Rodriques et al. 2013, they publish the demographic parameters of a previously undescribed hummingbird species in southeastern Brazil. Simply by observing the same species monthly for 2 years, scientists were able to collect and publish data regarding this hummingbird’s population dynamics, survival rates, sex ratios, mating displays, migratory patterns, and recommended conservation efforts. Here at RLT, with managers onsite 365 days per year, a focused study on each individual species could give us an accurate depiction of each species ecology, also known as a biographical sketch. For example, below is a photo of one of RLT’s most historically common hummingbirds, the Andean Emerald (Amazilia franciae). Managers have been recording high numbers of individuals from this species at our feeders since their inception in 2014, that means we have over 7 years of population data, behavior assessments, site fidelity, and banding data (which is technically in a separate database, but we have it and could supplement our surveys with it!). We have ALL of this knowledge at our fingertips, however there are NO publications (that I could find anyway) which draw out a biographical sketch of this species. What if this is a keystone species of hummingbirds in the neotropical region? We should have its ecology listed out and available for conservationists to use if need be in the protection of environmentally sensitive areas. There are some excellent opportunities here for students looking into higher education, just saying 😉

Well, I hope we didn’t bore you with TOO much science talk during this blog…but that you did come away with some new information regarding our “customers”. Also, just for your information the reason we call the hummingbirds at the feeders “customers” is because tourism in Ecuador is still relatively low, so we are only being visited by the occasional hiker…however, we KNOW that we can depend on these hummingbirds showing up Every. Single. Day. within seconds of our appearing outside with the feeders, hence they are our biggest customers, at the moment.

If you want to come visit us at Reserva las Tangaras and learn more about our “customers” or assist with one of our daily hummingbird surveys, call or WhatsApp us to schedule your visit: +593 96-982-4972 or +593 99-058-7084

We hope that you enjoyed this blog post and that we see you at RLT soon!

Best, Katie & Nick

Bandivadekar, R.R., Pandit, P.S., Sollmann, R., Thomas, M. J., Logan, S. M., Brown, J. C., et al. (2018) Use of RFID technology to characterize feeder visitations and contact network of hummingbirds in urban habitats. PLoS ONE, 13(12): e0208057. www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208057[c1]

Calder, W. A. III, Waser, N. M., Hiebert, S. M., Inouye, D. W., and Miller, S. (1983) Site-Fidelity, Longevity, and Population Dynamics of Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds: A Ten Year Study. Oecologia[c2] , 56 (2/3): 359-364. www.jstor.org/stable/4216906[c3]

Camfield, A. F. (2003) Quality of Food Source Affects Female Visitation and Display Rates of Male Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds. The Condor[c4] , 105(3): 603-606. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1370686[c5]

Feinsinger, P., Murray, G. K., Kinsman, S., and Busby, W. H. (1986) Floral Neighborhood and Pollination Success in Four Hummingbird-pollinated Cloud Forest Plant Species. Ecology, 67(2): 449-464

Hadley, A. S., Frey, S., Robinson, D. W., and Betts, M. G. (2018) Forest fragmentation and loss reduce richness, availability, and specialization in tropical hummingbird communities. Biotropica 50(1): 74-83 www.doi.org/10.1111/btp.12487[c6]

Jimenez, L., Negrete-Yankelevich, S., and Maćıas-Ordónez, R. (2012) Spatial association between floral resources and hummingbird activity in a Mexican tropical montane cloud forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology (2012) 28: 497-506. www.doi.org/10.1017/S0266467412000508[c7]

Ornelas, F. J., Jiménez, L., González, C., and Hernández, A. (2004) Reproductive ecology of Distylous palicourea padifolia (rubiaceae) in a Tropical Montane Cloud Forest: Hummingbirds’ Effectiveness as Pollen Vectors. American Journal of Botany 91(7): 1052–1060.

Rodrigues, L., Ibanez Martins, F., and Rodrigues, M. (2013) Survival of a mountaintop hummingbird, the Hyacinth Visorbearer (Augastes scutatus), in southeastern Brazil. Ornithologica[c8] , 48 (2)

Finca “Reserva las Tangaras”

We arrived at the reserve with the promise of an “orchard” but what we found was 20 moss covered and undeveloped lime trees; 10 stands of overgrown and undermaintained bananas; along with a few avocado and coffee plants that seemed to have seen better days. Furthermore, the jungle was encroaching on the orchard, testing the borders with vines, saplings, and decayed treefall. We know the previous managers tried to produce something viable and we are not knocking their efforts, the pandemic and lack of oversite were the main reasons why the orchard was in need of some maintenance. Left as is, the orchard would produce nothing more than bitter disappointment.

As aspiring homesteaders, avid guerilla gardeners and all-around veggie-heads, we placed “creating a finca (farm)” high on the list of projects we hoped to achieve while we are managers here at Reserva Las Tangaras. This job would not come easy and, with even the shortest seed to harvest time taking around three months, would yield little “fruits of our labor”. However, when looked at life from the perspective that the rewards are not in the results but rather in the process, creating a functioning farm from nothing is just as sweet as the first harvest that we will probably never get to enjoy. We hope that future managers and their guests benefit from our efforts and that they too enjoy working to sustain the little finca that we have brought back to life.

Finca Las Tangaras has its roots in three goals: that it provides abundance in harvest and variety; that it is a free as possible to set up and perpetuate; and that it requires little effort or inputs to maintain. Let us start with the economical goal first: we wanted the farm to be established and run for as little extra cost to the reserve or to ourselves. In the most basic terms, you need four parts to grow a plant: light, water, a nutrient rich medium and the plant itself. Mother nature provides the first three of those four inputs, in varying levels of abundance, but all for free. Historically, in the months of December through to May (the duration of our tenure here) we are expecting 5 to 8 feet of rain. Yes, you read correctly, that is so much free water falling right out of the sky. The landscape here not only provides part of the nutrient rich medium, which is the molasses-colored soil found all around us, but also gentle slopes which can be channeled to increase or decrease water to certain areas of the finca. The rain does not last forever as summer months see little rainfall, so planning is needed to retain as much of the infrequent summer rains as possible. The last of mother nature’s gift is light, provided by that glowing dot of plasma we call our sun. Judging by the high amount of rainfall we expect while we are here, we also expect low hours of sunlight. This means that plants will not grow as much as they would in summer months when the sunlit hours are longer, but that does not stop them from becoming established during the rainy season. The last part of the economic equation is the plants themselves. We chose to source them from kitchen scraps of food that we would buy to feed ourselves such as garlic, onions, peppers, cilantro, basil, and scallions or try to get cuttings of cassava and sugar cane, for example, cheaply from local farmers. So far, we have spent a grand total of $0.00 on the farm, other than buying food to feed ourselves, but have 10 varieties of plants growing.

It is our hope that those 10 varieties grow to 30 and that there are enough of those 30 varieties to go around. Abundance not only comes in what you can produce but that you produce enough that you can eat some of it fresh, preserve some of it and still have enough to be able to produce seeds or replant. The man-made economy has a truly evil way of copyrighting and trademarking everything, including the seeds of most of the produce that we eat. What we are doing here may be illegal in some jurisdictions, as people should be rebuying seeds from giant corporations such as Mansato but, we feel that what is illegal is not always immoral. Possessing the ability to replant your own food means that you possess a perpetual state of abundance and control the seed to harvest to seed cycle without the need to fatten some corporation’s already bludgeoning pockets over some ridiculous law.

Our time here is short, and most grow cycles are long, with a schedule of maintenance that needs to occur to keep the finca up and running. We do not expect all managers to have a green thumb (or even keep the farm running at all) but we hope that they will see the value of spending time growing their own food, rather than having to walk a total of 4 hours to town and back, half of which would be walking loaded with a backpack of food. For this reason, we have written a guide to planting, maintaining, and harvesting each of the different varieties of produce that we currently have and will have available in the finca. The guide should provide managers with even the highest plant mortality rate to keep them “in the green” if followed correctly. Additionally, the design of the finca itself provides low maintenance systems so that future managers can almost sit back and watch the food grow itself. Take for example our compost system. We go through roughly 1 to 2 lbs of food scraps every 2 or 3 days. Instead of going into the garbage, we throw these scraps into one of four compost pits, filled in on a cycle to reduce smells and increase compost production. These pits will not only generate nutrient rich compost (the starter for many a plant to come) but also act as water sinks to provide a pool for banana, cassava, and papaya plants to tap into when rains are low.

Our principles are based on Permaculture and experimentation. Watch what lessons the plants and the forest teach that day. Trust us, there will be many failed banana plants before the first successful one comes bearing fruit. Permaculture courses are freely available in most cities and online, so we implore you to start growing your own food at home and stop paying the companies who produce the insecticides, pesticides, hormones, and genetically modified foods that are bad for our planet, for our health, and detrimental to the livelihoods of our farmers. Also, follow us on Instagram @reserva_las_tangaras_mindo and Facebook @ Reserva las Tangaras for periodic updates on how our finca is growing, all of the delicious produce we manage to harvest, and the creative ways we put it to use.

Coming to live in the Jungle, or more specifically…to a neo-tropical montane cloud forest

On Christmas Day, as we were calling loved ones, a friend asked us to “describe the mountain in front of us” and it made me realize that unless someone has been here, it is impossible to know what to expect upon arrival. A “mountain” can be so many different things. Dependent on who you are and what places you have experienced in your lifetime, determines what image is conjured up in your mind when you hear that word. You can Google Earth the location, you can read the Reserve’s Managers Blogs, you can research photos and videos of the Mindo, Ecuador area but, until you have arrived here at Reserva Las Tangaras, you cannot know what it is like to be surrounded by this kind of nature.

As I sit here writing this, I am struck by the absolute emerald quality that everything holds. On the days like today, where we are lucky enough to welcome the sun first thing in the morning, the forest seems to be drawn into its light. All the plants are growing and reaching towards the suns warm, enriching rays. Everything sparkles for the first few hours as the dew slowly evaporates from the forest surfaces. Spiders webs, meters long are strung across the lawn like natural tightropes, catching the light for just one second before disappearing into the forest backdrop. The colors here indescribable.

We fall asleep each night to the frogs and wake up each day to the birds. Each the perfect chorus to lull us to sleep after a long day or to gently welcome us to a new beginning. In the background you can hear the Rio Nambillo as it pushes massive amounts of water along its shores. Today, the sounds of the river are in the backdrop as we have had little rain over the last 24hrs…not the case only 48hrs ago. Two days ago (Christmas Day) we had about 60mm of rain in a 24hr period and sitting in the lodge you could feel the boulders being moved under the rivers surface. By comparison, today’s river is calm.

I can hear a Broad-billed Motmot in the forest to the west of la cabana, it’s familiar “ Gwau, gwua, gwua…” slowly and steadily calling. There are many other smaller birds in the area calling as well, however my novice knowledge of the local avian populations does not allow me to identify them. They seem to always be calling over one another, fighting calmly for space in this active forest to be heard. There are insects as well, always a backdrop of insects rubbing their legs or wings together. They are a constant, faint, backdrop which becomes so normal to life here that you have to stop and close your eyes in order to give them the attention they deserve.

Hummingbirds thrum past you seemingly at random and in a blink of an eye they’re speeding back towards the cover of the forest. Their tiny beating wings so fast, that you feel the small wind produced by them as they inspect you for flowers before realizing their mistake. Some call, while others are only made apparent by the sound and feeling of their fast-fluttering wings.

Daily life here as you can imagine is magical. The work is physically demanding, labor intensive, and ever present. However, the reward for your efforts are unbounding. We have so enjoyed the first month of our stay here, cheers to the next five!

Your new Reserva Las Tangaras Managers, Katie and Nick

A Fridge-less Life : Off grid living in the Ecuadorian rainforest.

The magic of Las Tangaras Reserve is partly due to its remoteness. The wildlife is used to being undisturbed by crowds, traffic and bright lights and visitors often remark upon the tranquillity of the area. Of course this peacefulness comes with some challenges: low power and a long way to carry supplies. A frequently asked question is how just we manage living “off-grid”.

The Las Tangaras lodge is all but self-sufficient out of necessity as well as out of kindness towards the environment. This is my first time living in a self-sustaining house and, to me, the technology used to provide utilities is brilliantly simple. The running water is fresh from the Rio Nambillo and the water system is powered entirely by gravity. From the house, the water pipes lead up and into the forest, towards the source of the river, and some of the water flowing down is re-directed to us – no pump required. Gas bottles for hot water and cooking are carried in by mule or by ourselves. Electricity is provided via a solar panel that powers the LED fairy-lights that illuminate the house. We already knew that the house ran on a small amount of power and when we arrived at the Las Tangaras lodge our suspicions were confirmed. Definitely no fridge.

Which is why were surprised to find that, four months later, our eating habits haven’t really been compromised. We are not going grocery shopping every other day and we aren’t living off of tinned food. Most of this is done through meticulous planning. We write a menu each week. Cheese and perishables are eaten early in the week and dried rice, beans and pasta make up most of the meals towards the end of the week. Meat however is off the menu most of the time. Without a fridge, we would rather not risk storing it – especially if we are serving guests! As a result if you are a guest at Las Tangaras the menu will be largely vegetarian and pizza, shakshuka and tigrillo are becoming our specialities. One thing that really helps with meal planning is the managers cookbook. Here previous managers write their recipes for meals/ desserts/ snacks that have ingredients you can buy locally and don’t need refrigerating. We are especially grateful to the managers who wrote in their muffin recipe, we have worked out that we have baked and eaten about 60 muffins between us in the last two months.

So we have heroically overcome the absence of a fridge*. The next challenge is the distance to the Las Tangaras lodge. When we are not carrying groceries, the hike through the forest into the reserve takes about 45 minutes but usually longer because there is always something to see. For instance, when we were last maintaining the trails we saw ten (!) toucans all feeding together and a rainbow forest racer snake sunning itself by the footpath. However, this is a long time to be weighed down by shopping bags so naturally we try to lighten the load. Drinks are heaviest so we make our own soft drink from the orange-lime hybirds by the house (“orange-lime-ade” is delicious but needs a catchier name) and brew our own ginger beer to avoid carrying glass bottles. Another trick is to use the bananas that grow in the reserve garden. When they are green they are great substitutes for plantain and can be used in typical Ecuadorian dishes like tigrillo, bolones or just plain patacones. It is always a race to use them before they start turning yellow but once they are yellow then, well, we have bananas.

While all this may sound like a lot of hassle in order to achieve something as basic as eating, it has become second nature and we are actually hoping to retain some of the habits we have learned. It turns out that having no fridge means you end up with a diet that is more economical, healthier and more environmentally friendly. For instance, being forced to only buy what we really need reduces the grocery bill considerably. Not being able to refrigerate food means that ready-meals are off the table and all meals are freshly prepared and as a result taste better, are healthier and cheaper to produce. The mostly vegetarian diet is kinder to the environment and when we do go into town and eat meat or fish we really do appreciate it.

As our time as the managers of Las Tangaras draws to a close it has made us reflect on the lessons we have learned here. One is how little we really need some of the things that we normally take for granted as essential. By the time we leave, we will have lived for 5 months without a washing machine, without a fridge and without a real bed and somehow it is just not a problem. I initially assumed that having no fridge would mean extreme dietary restrictions for us. In fact a fridge-less life has forced us to re-think how we go about eating and our stay at Las Tangaras has been a far more creative and interesting experience for it.

*The absence of a freezer was also heroically overcome by simply eating ice cream within seconds of purchase.

A Day at the Reserve

Three months have passed in what seems like the blink of an eye. We arrived at Reserva Las Tangaras in the middle of July, full of enthusiasm and expectation and still a little relieved to have made it here at all given the ongoing pandemic which, as I type, seems to have the whole of Europe gripped in a second wave of rising cases.

Here in Ecuador things seem to be getting better due I’m sure in no small part to the way the countries population have adhered to the government’s containment and prevention measures. Only now are we starting to see a few unmasked people walking the streets as the government updates it’s advice, but every business be it a shop, restaurant or bank still insist on masks being worn and hands being sanitised upon entry. Everybody is treated equally, and I think the population accept that measures such as these, coupled with social distancing and limits on the number of people gathering in one place have helped reduce the spread of infection.

As the Covid-19 situation improves here we are hopeful that international tourists will soon start to return to the area. Mindo is relatively isolated yet easily reached from the capital, Quito. The town and surrounding area has so much to offer the inquisitive traveller – it’s possible to ride a cable car to take in some of the amazing views, visit waterfalls and ride the river rapids in a rubber ring. Food and cultural experiences are plentiful and of course you can come and stay at the reserve or just visit for a day and let the peace and tranquillity of nature surround you.

Ideally placed on the edge of the Mindo-Nambillo protected forest, the 50 hectare reserve is perfect for visitors who want to get in to the heart of the Ecuadorian cloud forest and see some of the amazing fauna and flora that help make Ecuador one of the most biodiverse countries on the planet. More than 15 species of hummingbird are virtually guaranteed and in 13 short weeks our patience and I’m sure a small amount of luck has been rewarded with sightings of Puma, Capuchin Monkey, Coati, Agouti, Rainbow Forest Racer snakes, Andean Cock-of-the-Rock and too many other animals to list…

We’ve started to settle into a routine here and have a weekly schedule of work that sees us tackle jobs ranging from bridge repairs and trail clearing through to creating marketing material and hosting guests. There are tasks we like and there are tasks we like less but if we had to describe an ideal day this is what it would look like.

The day would start early, we set our alarm for 04:50 as this is the time you have to roll out of bed if you want a front row seat at the sunrise Andean Cock-of-the-Rock lek display. It’s a 20-minute hike uphill from the cabin to the lek site and but the headtorch illuminated walk is well worth it. There’s always the chance you’ll catch the eyeshine of a tree dwelling mammal like a kinkajou on the way up but even if you don’t, being on the ridge of the hill as the suns first rays emerge and bring the forests birdlife in to song is reward enough.

As the rising sun pushes back the nights darkness the stars of the show start to arrive. The calls begin off in the distance but before long you can make out the unmistakeable silhouettes of the Andean Cock-of-the-Rock males gathering on their favourite perches. Almost immediately the show begins as each male starts his display in order to catch the eye of any visiting female.

It’s quite a sight to behold, the lek can attract in excess of 12 birds and between the calling and the dancing you don’t know which direction to point the binoculars or camera. Often, I find myself taking a step back and just trying to take in the whole spectacle.

When a female arrives, things go up a gear, the noise amplifies and displays become more energetic. Having observed many of these morning spectacles there’s no mistaking the moment a female bird is on the scene, but she doesn’t usually take long to make her choice and as quickly as she arrived, she’s gone and the urgency amongst remaining males subsides.

In total the morning performance can last anywhere between 40 minutes and an hour and a half although the main group has usually dispersed by 07:00.

For me the drop in activity signals the time to return to the cabin. This time in the morning is often the best for bird watching and the 20-minute journey back down the hill can often take an hour or more as there are so many opportunities to observe birds feeding and going about their early morning routines. The forest feels alive with activity from floor to canopy.

Once back at the cabin a hearty breakfast is in order, an additional reward for the early start – on an ideal day it would consist of a stack of fluffy banana pancakes or a couple of slices of still warm French toast, drizzled with some local honey or served with a side of spiced apple compote – all washed down with a strong cup of café pasado.

With breakfast out of the way and a renewed spring in the step it’s time to set-out and collect the camera traps. Often placed in remote and quiet corners of the reserve the camera traps act as an ever vigilant pair of eyes, keeping track of any goings-on day and night. With the traps in hand is back to base to see what activity has been captured. It’s always an exciting moment, placing the SD card in the computer as hope is high for a fleeting glimpse of one of the reserves more elusive inhabitants. Maybe today is the day we finally get that shot of the Puma or the Jaguarundi but to be honest, we’re always happy with whatever turns up!

Now the real work starts and it’s out into the reserve proper with machete and saw in hand to do some trail maintenance. The forest is a dynamic place and without regular attention the trails would soon be reclaimed, and visitors would not find it so easy to explore. Heavy rains and high winds can easily bring down tree limbs already burdened with the weight of creeping vines or bromeliads. Even for a couple of active stewards like ourselves it’s not possible, or sensible to try and tackle more than one trail a day but a couple of hours of intense grooming with the machete works up a good sweat and is usually enough to get the job done.

By now it’s early afternoon and with so much already achieved and the sun high in the sky it’s time to down tools and head to the river for a revitalising dip in the crisp and clear waters of the Nambillo.

At the reserve we’re lucky enough to have a couple of safe swimming holes that have been created in back eddies of the swift flowing water and a few moments spent washing away the mornings hard work are enough to remind you that lunch is long overdue.

You might think that the reserves’ isolated location and lack of fridge would restrict the menu but it’s quite the opposite. It’s been said that limited options encourage creativity and we have certainly found this to be true. Our repertoire of dishes has increased, and we are using ingredients that we might have previously ignored, especially dried beans and pulses and fruits and vegetables that you would not find on the shelves of a UK supermarket.

After a good lunch it’s time to turn our attention to data collection. We make a daily survey of the hummingbirds that visit the cabins’ 3 feeders and note down information the number of species we observe, the number of individual birds and their gender split. This is always a special moment in the day as it’s a period of intense bird activity and it’s possible to watch up to 23 species flit form feeder to feeder jostling for their position on one of the plastic flowers. Their reward is a sip of diluted sugar mix which we make for them daily.

Once the survey is complete the days work is done. Now it’s time to relax with a good book selected from the cabins’ small library and read through to the light fails. Days are regular here, close to the equator. The sun rises at 06:00 and sets at 18:00, give or take 10 minutes and the darkness creeps back as quickly as it was chased away by the sun in the morning.

The LED lights come on and we turn our attention to dinner. This is as exciting an event as lunch and after 3-months we still approach the cooker with a sense of enthusiasm.

The perfect day is topped-off with a well earned glass of homemade ginger beer and a game of cards (which I always win) and it’s not long before bed is calling and thoughts start to drift to what exciting adventures tomorrow will bring…

It’s what you don’t see…

The title is a bit misleading as you can actually see a lot of what you don’t see if you’re looking (and listening) carefully…

I’m new to the jungle, not just in terms of this trip but in terms of life experience. I’ve done a ‘Jungle trek’ once from Rio de Janeiro which consisted of a 2 hour jeep ride in to what appeared to be a large expanse of jungle behind the vast city of Rio and then what a brisk hike to a very picturesque waterfall for a bit of splashing around followed by a brisk hike back to the jeep. There was not a lot of time to dwell on the surrounding fauna and flora, but as a group we were lucky enough to come across a large wasp stinging a tarantula to death in order to lay it’s eggs (so we were told by the guide). Other than this brief experience and the vast array of documentaries I’ve watched on TV over the years I built myself a preconceived idea of what jungle life was going to be like!!

How wrong I was. First of all, I’m not living in just any jungle, I’m living in tropical montane cloud forest and secondly, the jungle fauna is not just hanging around waiting to be seen but if you use your eyes and ears, you’re patient and you’re careful where you put your feet, the jungle inhabitants will reveal themselves to you.

Let’s take mud, not a thing one gets terribly excited about, but in a tropical montane cloud forest (in July and August) there’s plenty of it around as rain is common. It didn’t take long to start noticing that amongst my own muddy footprints there were signs of what had passed before me.

It must already be clear that I’m not a biologist, so you’ll understand that coming across sets of muddy animal prints didn’t immediately trigger a process of animal track recognition from a university course that I didn’t do. However, I am a mobile phone user and through the power of technology I managed to take pictures that I hoped would help identify my unseen jungle companions when I got back to the lodge. Even with its small library of reference books, identifying animals from their tracks is not as easy as it sounds but the images I took were enough to narrow the owner down to family and in some cases individual species. What was especially useful was having the camera traps set to confirm that we weren’t seeing Paca, Red Brocket Deer and Agouti.

The next clue to the existence of animals we weren’t seeing was also a visual one, they leave behind droppings. What is consumed at one end is in part excreted at the other…

Although we’re not seeing a lot of animal faeces, what we are seeing points to the existence of small carnivores. In the two samples I’ve managed to picture, both have been relatively compact and there is clear evidence of fur.

Not long after arriving at the reserve we were lucky enough to see the rear end of a puma disappearing into the jungle but just the size of this cat rules it out as the owner of the droppings. We have also captured both Tayra and Jaguarundi on our camera traps so either of these could be the owners but there are also reports of Ocelot and Margay on and around the reserve so it’s a possibility either of these cats could be responsible.

The last piece of evidence for the existence of unseen jungle companions is sound.

On more than one occasion, and once night has fallen, we have heard strange sounds coming from around the lodge. A torch lit inspection has failed to yield any results, but the loud snuffling suggests a foraging armadillo.

In the early morning, just after sunrise and towards dusk, the air is often filled with the sound of bird song. Spotting birds is easy in the jungle, they’re all around but if you only use your eyes for identification then you’re just scraping the surface of what’s out there. There are some obvious calls, like the Andean-cock-of-the-rock and the Choco toucan but if you listen carefully you might pick out the staccato pipping of an ornate flycatcher or the mocking chuckle of a well-hidden quetzal. There are some really good mobile apps to help with the identification of birds by their call and although in the 8 weeks we’ve been here we’ve spotted over 70 different species we know that we’ve got a long way to go to hear, and hopefully see more of the 300+ species we know inhabit the reserve.

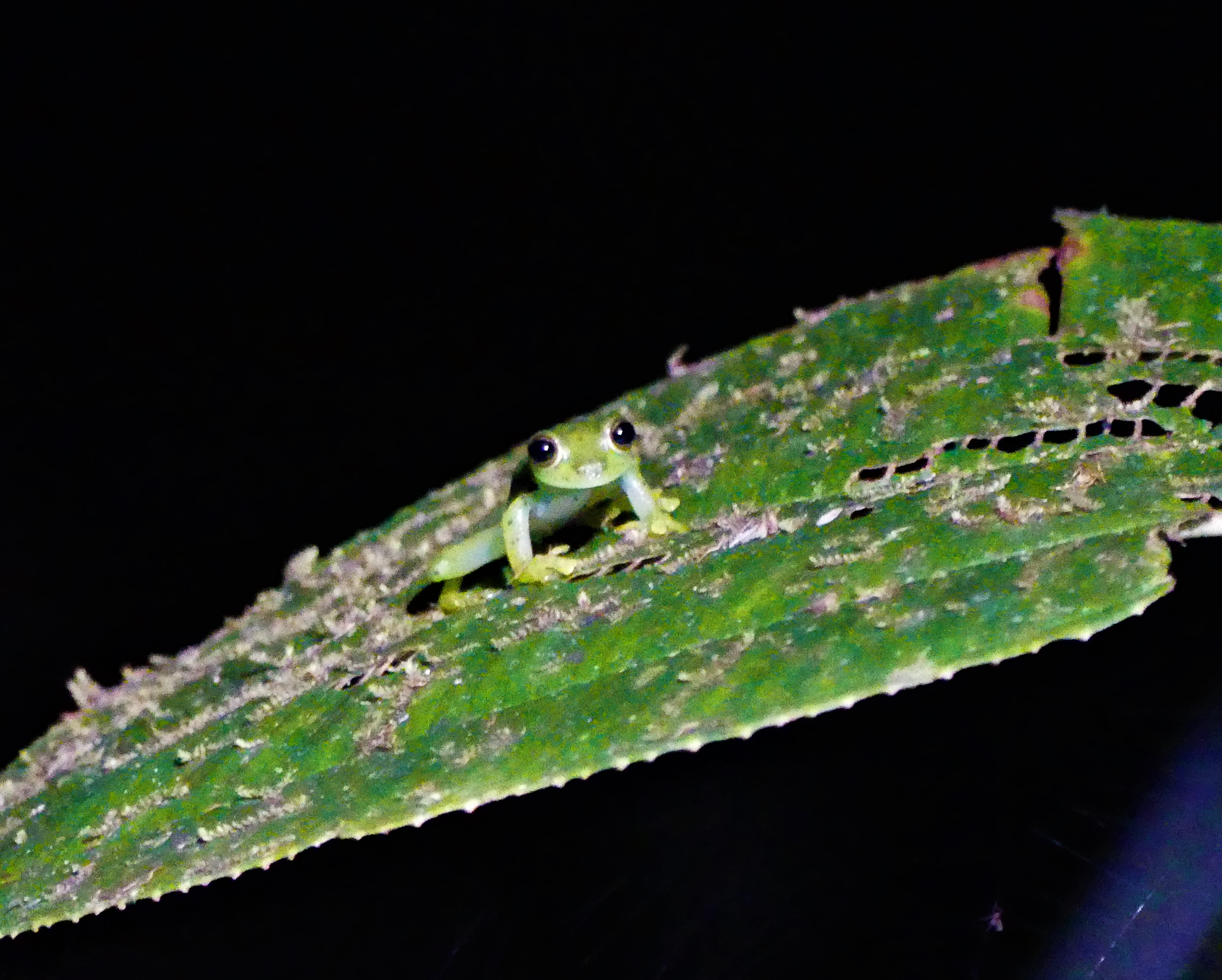

The onset of another tropical shower or the arrival of dusk signals the jungles many species of frog to begin their ritual calling. Pastures rainfrogs, emerald glassfrogs and yellow-groined rainfrogs can be seen and heard easily enough but a keen and experienced eye is needed to spot many of the other species that are hidden in the leaf litter or up in the trees.

At night rarer species like the Mindo rainfrog can be heard calling from up in the trees and on our Tres Tazas trail we have been teased by the sound of the Darwin Wallace poison-frog but have yet to find our first specimen.

The failing light of dusk also gives confidence to the millions of insects that inhabit the jungle. From roots to treetops the sound begins to build as individuals call-out to attract a mate. Crickets and katydids do battle for who can shout the loudest and although you can’t always see them you know you’re not alone…

Reserva Las Tangaras is a home to hundreds of different species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, bugs and fish. It would be impossible to see them all, or even get close to it even with an extended stay but it’s reassuring to know that there are clues left all over the reserve to help you see what you don’t see!

Jungle Nights

I woke up during the night a couple of weeks ago to find that a cloud had settled on the lodge. Living in the montane cloud forest, we regularly find ourselves above clouds or even in them depending on the weather conditions. That night, the conditions must have been exactly right to have the cloud at precisely the level of the lodge. The close-to-full moon was lighting up the cloud making it glow and give the lodge an ethereal quality. As if to complete the eerie and magical scene, fireflies flashing red and green were hovering lazily above the mist.

It reminded me how special the jungle is at night. It’s something many people don’t choose to experience or even actively avoid. I imagined the first time I entered the forest at night, that it would be a stressful experience of wandering through creepy, quiet darkness with the vague feeling that you are being watched by something that you cannot see. I was wrong for the most part. First of all, the rainforest at night is LOUD. The chorus of birds heard throughout the day is replaced by an equally enthusiastic chorus of insects and frogs. While indeed the remote forest is dark, the darkness can have its benefits. Since the Las Tangaras reserve is far away from the artificial lights of inhabited areas, there is no light pollution to mask the starlight. If you are walking in Las Tangaras on a clear night, it is well worth turning off your head torch and looking up to see a sky full of more stars than you are likely to have ever seen. As for the feeling of being watched…well you probably are, but this is true in the daytime too and the vast majority of creatures in the forest would much rather slip quietly away from you than risk any confrontation.

Spiny Stick Insect

Also, rather than stressful I find walking in the forest at night quite relaxing. The air is pleasantly cool and you keep your walking speed extra slow. This is for two reasons. Firstly because walking fast in the jungle at night is a recipe for tripping over a root and falling flat on your face. And the second (and more exciting) reason is that you aren’t going to see anything interesting if you are speeding through the forest not paying attention to your surroundings. My advice is to relax and not rush when walking at night. Use your torch to search for the eyeshine of animals like kinkajou and opossum that may be watching quietly from the trees. Listen carefully for frog calls and then try to locate the caller. The air and plants around you are full of interesting insects from the smallest iridescent beetle to sizeable and amazingly shaped stick insects. The riverside trails at Las Tangaras are home to plenty of emerald glass frogs that sit on the leaves surrounding the paths and a common potoo has taken a liking to a tree near the cabin.

Our resident potoo.

I hope I’ve made a good case for the night time rainforest being a magical and fascinating place to be! If you happen to be in the area of Mindo I hope you stop by (by night or by day) and enjoy the forest with us.

Emerald Glass Frog.