Wild Waters

Water is, naturally, an element with a strong presence here in the rainforest at Reserva Las Tangaras. Whether rising as morning vapor misting up from the creek canyon, flowing in sheets across the broad yard a heavy downpour, or rushing down ever-incising channels to join other rivulets until they become something we might call a creek or river, water is everywhere. At least that’s how it’s been feeling this time of year, nearing the end of an “El Nin~o-year, Wet-Season.”

For sure, the rains have been strong and steady throughout the month of April, with occasional gloriously sunny mornings that give witness to transpiration in action: “steam” rising from plants into the atmosphere all around you. We closely monitor daily precipitation here at the Reserve, and roughly one-out-of-three days has dropped more than an inch of rain. A few days ago, we had a daily record for 2024, with over 4 inches (110cm) falling in less than 12hrs.

All this moisture, on these steep mountainous slopes, can wreak havoc on human logistics. The main road between Mindo and the capitol has been closed down several times due to mudslides, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days. Twice now, returning to Mindo on errands requiring visits to bigger towns, Anastasia and I have encountered stopped-dead traffic in both directions, and ultimately needed to disembark the bus, walk past a mile-long train of cars and trucks, encounter the mass of mud and rock spilled across the roadway, and join the intrepid others who, like ants, have mucked a pathway through the safest way to traverse the mudslide on foot. From there, it didn’t take too long to find a driver that was ready to give up on the wait, turn their vehicle around to give us a lift back to town.

On the Reserve, more rain means more trees coming crashing to the ground. On a recent phone call with my brother in northern California, he asked what causes all the tree fall. He lives in the pine forests of the Sierra Nevada and is accustomed to cleaning up downed timber, so the question came as one keen on the details of forest dynamics. In his California climate context, extended drought has weakened the conifers and they will fall from high cold winds snapping the weak and freezing trees half-way up the trunk. Or, a sudden downpour of rain in autumn will inundate the rootballs of trees on slopes that haven’t received a drop of water for half a year, and down they’ll tumble in a slurry of soil.

Here on the equator, treefall happens because of the optimal growing conditions for plant life, the steepness of the terrain, and all that water. Lightness and dark share the day equally—11 and half to 12 and a half hours of sunlight regardless of the month, although that sunlight is often dispersed by cloud cover. The temperature is (nearly) always somewhere between 60 and 80 degrees, day or night, January or June. Add water daily, in small or large doses from the ever-giving sky, and you’ve got ridiculous plant productivity. Trees can grow tall quickly, and many will readily play host to mosses and epiphytic plants that hold moisture and grow heavy.

In the dense forest, top-heavy trees will stretch out wide in the competition for sunlight until the slope of the terrain, the heft of the hangers-on—massive bromeliads out on branches, vertical carpets of orchids up the trunk, a tangle of fig vines dropping down the tree—the slow rot within the trunks, and soil saturation levels are all factors that conspire to topple trees almost daily in this environment. As a roadless Reserve, the extra water this month has kept us busy with clearing our all-important trails, which serve as the pathways for our guests’ enjoyment, access to our water source, the route to bird monitoring stations, and the way we re-visit with the outside world.

Indeed, water abounds on this landscape and—like this blog—eventually seeps or cascades down to its flowing purpose: the Nambillo River and two of her tributaries.

The Nambillo serves as a boundary to this fifty-hectare nature reserve, and two perennial creeks frame two other borders. (The fourth boundary line that closes the rectangular property is along the primary forest ridgetop, which drains this land.)

I have a strong affinity for flowing water, probably instilled from early childhood on the South Yuba River (in California) and deeply distilled during a career where I was known as “the river guy.” I worked with various organizations and social movements–employing a range of strategies, in river basins from California to Zimbabwe–all in service of the protection of free-flowing rivers, the biodiversity they support, and the ecological functions they play. So I can’t help but be interested in all manner of questions about the river that rushes below the front balcony of the lodge at Tangaras. Alas, limited bandwidth (meaning access to the internet, as well as available time for pet research projects) hasn’t allowed me to deeply investigate the Nambillo River, but I can share what I observe…and what you as a visitor can experience along the banks of our river and creeks.

The Nambillo is what my fluvial geomorphologist friends might call a “flashy” river system. While I wish there was a flow gauge that monitored the changes of velocity and volume of the river, you don’t need a measurement to witness how dramatically the river rises during a rainstorm. Within an hour, a clear river of smooth riffles and runs can turn into a roiling brown torrent of jarring power–very exhilarating when crossing the footbridge! In really big storms, from the lodge we can hear, and feel in the floor boards, the river carrying large boulders thunderously downstream. The river flows through a very steep and deep gorge when it enters the Reserve property When the rains stop, give it a half-day and river velocity seems to drop by orders of magnitude, the deep brown turbidity clears, and one can almost feel tempted to wade into the shallows or take a dip in one of the several “pools” along our stretch of the Nambillo.

As for our two tributaries, one is the (locally) famed “Cascade Creek”. The series of waterfalls is popular not so much because of the great heights of the falls, but the pure beauty and clarity of the water and the azure swim holes that are formed in the plunge pools. As one of Mindo’s most popular attractions, 99.5% of visitors (I’d estimate) reach the “cascadas” by taking a cable car across the Nambillo and hiking down to the waterfalls. However, we share the waterfalls as a boundary line with our neighbors, and we are able to guide guests on a hiking tour to these cascades.

The other tributary, roughly on our eastern border, is very remote and generally inaccessible. We call it “Fountain Creek”, because it serves as the fount for our water source—crystal clear water that we pipe down to lodge. We have one trail (called Tres Tazas) that leads visitors to the creek’s confluence with the Nambillo, where our own private series of cascades and plunge pools cut through beautiful bedrock. The upper reaches of the creek are equally stunning. Because of the difficulty of reaching this area, and the sensitive of the area for our drinking supply, we only take our volunteers there on occasion. It’s spectacularly beautiful, and another reason to consider a longer stay at the Reserve as a Volunteer.

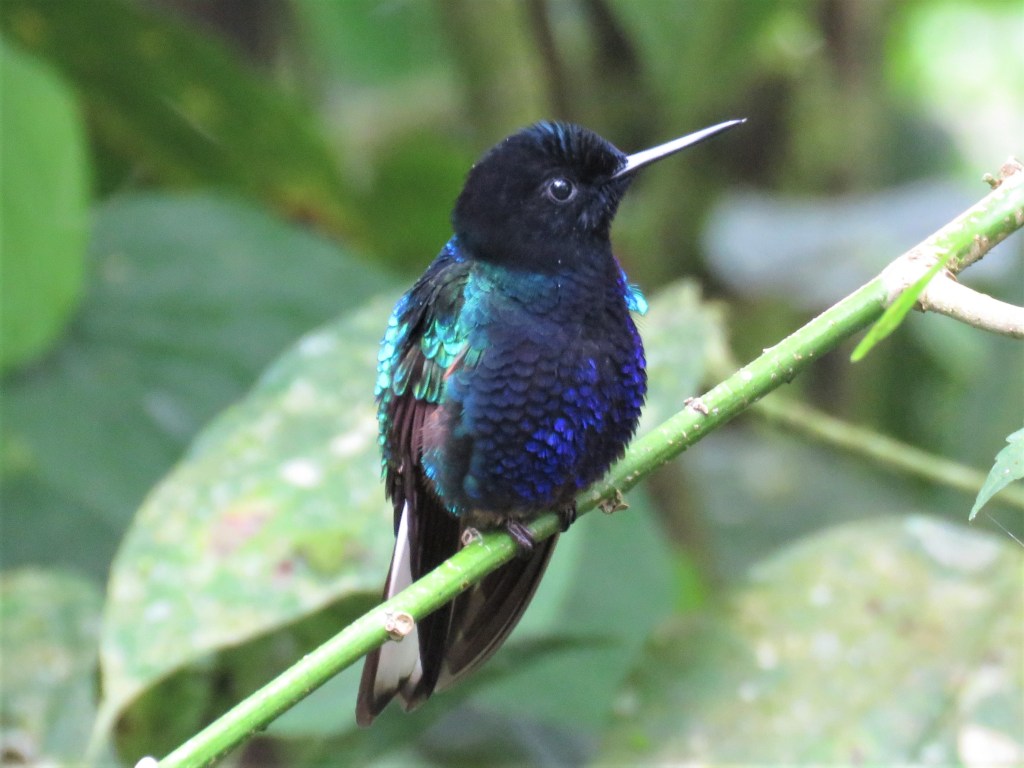

Finally, a word about the wildlife a visitor can encounter in the riparian zones—the unique forested river edges of the creeks and rivers. The birds are special: we regularly see Torrent Tyrannulet, Buff-tailed Warble, and White-capped Dipper (whose cousin, the American Dipper is a denizen of my home rivers in California). Rufous-gaped Hillstar and Green-fronted Lancebill are hummingbirds that clearly prefer the habitats along the Nambillo River and (at least at this time of year) we see them sallying from the handrail of our bridge. And my favorite reptile of the Reserve can also be seen basking on a warm boulder near the bridge—the Western Basilisk. This is the creature you might have seen on a nature documentary, in a slow-motion clip of a 2-foot-long lizard rising to its hind legs and running across the surface of the river (in my imagination, to the tune of the Violent Femmes song, “Jesus Walking on the Water”).

We also have many records of river otter plying the Nambillo, but we have yet to see one in our four months here. This sleek playful mammal is a bit of a totem-animal for me, so I’m confident we’ll spot one before our time at Reserva Las Tangaras conclude. Meanwhile, we keep our eyes on the river to discover the unexpected and wonderous. We invite you to join us and do the same. We’ll work to keep the trails clear for you, rain or shine!

Wild waters,

Jason (co-manager/volunteer steward)

?Que Actividades?

The question arrived about the only way a message can be received out at the Lodge at Reserva Las Tangaras–by a WhatsApp text to +593 99 058 7084—and was short, direct and in Spanish: Que actividades tu tienes?

As Anastasia and I arrive at the mid-point of our 6-month tenure as co-managers at RLT, it’s clear that the birds–and the conservation science mission and the protection of this unique piece of an equatorial neo-tropical montane forest—drive our enthusiasm for hosting visitors here at Las Tangaras. And, when the day’s work is done, the pure joy of just soaking in the natural beauty and fecundity of this forest seems like the thing to do. So, when asked without formalities, “What Activities do you have?”, I will admit feeling sour for an initial moment. “Activities?!?”, I thought to myself. “As in floating for 5 minutes down a boulder-strewn river in a bramble of inner tubes? Or harnessing-in and pedaling a “bike” [so “sustainable”!] along a zipline cable over the forest? If that’s what you’re after, cool, but that’s not us.”

But I quickly pulled myself back from the misplaced sarcasm: While it often feels that “adventure tourism” here in Mindo (such as roaring through forested roads on Quads rented by the hour; or whizzing along a sky-tram on a network of cables over the forest canopy) has overtaken this community’s well-earned reputation as a pioneer in locally-led, conservation-based, birding and eco-tourism (see in-depth article here), the question about what one might DO when visiting Las Tangaras Reserve was a sincere and genuine inquiry. And while it often feels to me as though the things to “do” in this particular 120-acre hotspot of global biodiversity are nearly limitless, let’s organize some of our favorite activities and things to do with visitors and volunteers, and have a little fun dreaming up some snappy labels for what you can do in a visit to this verdant and vibrant wonderland!

“Top 15 Activities @ Reserva Las Tangaras—the 2024 Unofficial List”

The Blockbuster Basics

#1 – Adventure to the Wild Side of the Nambillo River!

Reaching our remote Reserve, is an Activity in itself. Call it walking, hiking or birdwatching, the Reserve is reached by a 2km nature trail that we share with our neighbor “Sendero de las Aves” (for their clients, this IS the Activity). The 40-45 minute walk passes through several eco-types and the birding is good, so keep your binoculars at hand. Reach out to us via WhatsApp, and we’ll send you some of our bird-list highlights and favorite vista points and big heritage trees to look out for while you hike in. Oh, and 2-minutes before you reach our Lodge, you cross over to the “Wild Side” of the Nambillo River on our jungle-ready suspension footbridge. It’s exhilarating. Stay focused and don’t look down at the rushing water below!

#2 -See the Lekking of the Dawn!

Take a guided hike to see one of nature’s oddest displays of the macho-ego! The “lekking” of male Andean Cocks-of-the-Rock. A football-sized bird, with a fire-engine-red head shaped like you-know-what, the males posture, re-position, and thrust their caps at competitors in this age-old mating ritual, slurring and slinging raucous insults at each other (my interpretations, not necessarily those of our avian researchers). With about 20 of these guys going at it for over an hour…Things get violent, the ladies show up and copulations happen, and it goes down at dawn every day on the ridge above the Lodge, for at least the past 80 years. Reserve your spot & see what all the commotion is about. Overnighting at our Lodge the night before is highly-recommended for this Activity, which sets out at 5:15am!

For those with an Appetite and Half-a-Day

#3 – Reserve your place on our Viewing Deck for our Breakfast and Hummingbirds Special

For early-risers…Arrive at the Lodge between 7am and 9am, and enjoy coffee, tea, and an American-style breakfast on our deck above the Nambillo River. While enjoying the flavors from Anastasia’s kitchen, we’ll observe up to 15 species of hummingbirds and talk about RLT’s long-standing Choco-Andino Hummingbird monitoring project. [check out the promo on our Instagram account.]

#4 – Join us for an afternoon Lek & Lunch– Although not as well-attended, nor as raucous as the Lekking of the Dawn (see #1 above), many of the males of our population of Andean Cocks-of-the-Rock do assemble for a “Late-afternoon Lek.” We’ll enjoy a hearty lunch that Anastasia will serve up at 1:30pm on our deck above the Nambillo River. After lunch, enjoy tea or coffee and an informal talk and Q&A about the Andean Cocks-of-the-Rock and our 15+ years of research here at RLT. At 3pm, we’ll gather for a 30 minute uphill walk to the Lekking site. We’ll all return to the Lodge by 5pm, which will allow guests to get back to the main road/Las Tongas Restaurant before 6pm and dusk. More details and reservations on our Instagram page.

For those looking to “Connect with Nature” while in Mindo

#5 – Hike our Reserve’s “back-country” Trails.

We have over 20km of backcountry trails on our 50-hectare nature reserve, including secondary and primary forests from ~1250m to 1600m that adjoin the expansive Mindo-Nambillo Bosque Protector Reserve. Trails can be rough, steep and sometimes slick with mud, but they take you to places you can’t find elsewhere in Mindo. Birds abound of course—Toucans, Motmots and Tanagers—but just immersing yourself in this unique equatorial rainforest –in all its botanical abundance in full florescence–is a most enjoyable activity in itself.

#6 – Track the mammals that are at home in Las Tangaras

Evidence of the cool cats and charmed Spectacled Bear can be found throughout the Reserve. With our lightly used trails, and rain almost every night, this makes for places near the lodge where fresh animal tracks can be found most every morning. Use our animal track reference guides, or ask us to show you places where tracks of Margay, Ocelot, Oncilla and—perhaps—Puma can be found. You can also discover evidence of our bears (teeth marks on discarded bromeliad leaves), find footprints (and see) agoutis and Red Brocket Deer and the markings of armadillos rooting around in the sandy parts of our trails. Or maybe you’ll look up and see a troupe of monkeys (3 species here), an anteater, a coati or the sleek Tayra, a large member of the weasel family. It’s wild fun out here!

#7 Do the Blue Morpho Dance

The shockingly large Blue Morpho butterfly –with its wildly geometricly “designed” under-wings and iridescent blue upper wings—is a regular visitor at our banana feeders. If you wear the right shade of bright blue shirt (or borrow one from your hosts) and there’s a little sunshine, there’s a good chance the butterfly will ask you to dance. Don’t be a wallflower…get out there and show us your flutter!

#8 Go “Orchid hunting” with your friends and discover stunning flowering plants

There are thousands of known orchid species in Ecuador, and a lot of them are here at RLT. Walk our trails and make a “collection” (with photos only!). Who can find the smallest orchid flower (size of a pin-head), or the plant producing the most flowers, or the most spectacular flower structure? Getting tired of hunting orchids? Do the same for the Bromeliads…or see who can count the number of distinctive epiphytic plants on a single tree (more than 20, or 50 or one hundred?!?).

For those inclined to enjoy Passive and Nocturnal Activities

#9 Do yoga.

We have an incredible yoga deck on the loft of the Lodge, with sounds the river below chanting the mantras. Bring a yoga mat (we only have one!). There’s no guru to discover here, but we’ll lead you in some stretches, if desired. Try to keep that tree-pose, while gazing into the forest canopy with hummingbirds buzzing your head!

#10 Watch the River Flow

After Yoga, head down to the Nambillo River to one of our “beaches” to meditate. New to meditation? This is a fine place to begin your practice: just find a patch of sand or a driftwood log to sit on, rest comfortably and pay attention to the flow of your breath. Observe gently what happens around you, and within you. Repeat. Yeah, wow, “connecting with nature”, right?!?

#11 Join the Band

We’ve got a guitar, ukulele and number of song books here at the Lodge. Yes, pick up an instrument and learn a new song, or let’s just jam!

#12 Learn the ultimate “birders” board game: Wingspan

From now until June…come learn how to play this somewhat complicated but super-fun game called “Wingspan”. We have the base edition (North American birds) and the “Asian Birds” expansion pack…while we wait for them to create the “South American Birds” expansion pack. Be forewarned though: Anastasia’s pretty serious about winning! This activity is best suited for an overnight stay.

#13. Read a book for fun, or prep for doing a Master’s Degree in neo-tropical ecology.

We have an excellent little English-language library here. Two shelves of novels for good old fashioned “book swapping” (this was a big thing last millennium, before the internet: travelers the world-over swapping out reading books at backpacker hostels). Or, stay with us awhile and work through the volumes of books on tropical ecology, conservation planning, field research methods, and of course field guides to plants, mammals, insects, reptiles, amphibians and dozens of books on the birds of Ecuador.

#14. Take a night hike to see frogs, reptiles and nocturnal birds

If you’re serious about nocturnal reptiles and frogs, we recommend you contact our friends down the road at Ecuador Reptile Adventures—they bring their clients to our Reserve, because the frogs are better and more abundant on this roadless wild side of the Nambillo. They are experts, but in a pinch we could lead overnight guests on some amateur “herping” when night falls here at the Reserve. Maybe we’ll also see owls, or sleeping birds perched motionless in the trees.

#15. Get your groove on at the Sunday Fun-Day Dance party.

Those who enjoy Irie Island music know that most anywhere in the world, reggae fans gather on Sundays for music and dance…if they can find the local venue. Here in 2024, Reserva Las Tangaras seems to be “the place” for Sunday Fun-Day in Mindo. (Who would have guessed?) With a live DJ and light show, join your RLT hosts and get your jungle groove going strong. Don’t worry, we play all styles (eg. Roots reggae, Dancehall, Reggaetón, and Rock Steady…we’ll even play Ska and Dub Step upon request) so there’s a groove for everyone! The party starts when you arrive on any Sunday from now ‘til June (the resident DJ’s contract ends mid-June, so catch this Activity while you can).

As you can see…we have Activities at Reserva Las Tangaras! And we’ve observed that each of these activities seem to be appreciated (or ignored) by our feathered and four-legged residents…so come visit us before, after or instead of getting your adrenaline racing with Mindo’s popular “adventure” activities. Send us a WhatsApp, and let’s figure out something awesome for you and your group to do out here at the Reserve!

~You co-hosts at RLT, Jason & Anastasia.

A Hummer of a Q & A

Even in the short month of February, so much can happen out here at Reserva Las Tangaras. We’ve gotten into good rhythms to keep the Lodge well-maintained and provisioned, to know when to rest the machete arm after a morning of trail clearing, and we’re noticing patterns as we observe, monitor and count birds. We’ve also found time to search for monkeys, learn some frog songs, and explore this incredible rain forest Reserve with our guests. It’s difficult to choose which observations and stories to share out…yet our daily practice of an hour of hummingbird monitoring has been rewarding and a joy to share with our visitors and volunteers. We’re not experts, but here are responses to the many questions that arise when we gather on the deck to observe the hummingbirds here at RLT.

So what’s going on with the hummingbird feeders?

Everyday we thoroughly clean up to ten feeders and fill them with 1:4 sugar water. Anastasia’s been the lead on hummingbird care, usually done with the whole process with feeders placed on the far perimeter of yard and gardens before the first cup of coffee is brewed. We’re wanting to create an ideal environment around the Lodge for hummingbirds, and for their human observers. The feeders are a small, but important, part of that. Plus, it allows us to build upon a long-standing baseline of data on daily hummingbird abundance at RLT.

What do you record on that data sheet?

We remove all the hummingbird feeders on the property, except for 3 that we’ll concentrate in one viewing area. Then, for 60 minutes we take note and tally every individual hummingbird that visits the feeders or is otherwise seen “in the observation arena.” For birds that have sexual dimorphism, we take note of females and males observed, too.

How do you differentiate between “individual” birds?

A few ways. Of course, first we have to identify the species, and sex of the bird (if observable). Then, we’ll count more than one individual if and only if (1) we see more than one bird at the same moment; (2) we’ve familiarized ourselves with distinctive markings on a particular bird—which is easier to do with some species over others; and (3) perhaps an individual of a species will have a golden marking from pollen on a given day, but her “sibling” won’t…which helps us to affirm for example two female Green Crowned Brilliants. Fourth, some of the hummingbirds wear tiny anklets that help us track at the individual level! So, we’re cautious not to double-count any bird, and thus our data are conservative and give the minimum number of birds observed.

On average, how many hummingbirds do visit the feeders over the course of an hour?

Let’s look at yesterday’s data (Feb 28th)—over the course of the hour we observed 12 different hummingbird species, half of which can be visually differentiated between females and males. So, tallying up the marks on the data sheet, we observed a minimum of 26 individuals at the feeders or in the arena. That’s about average for any given day of this month, however we saw some nice birds yesterday, yet also didn’t get visits from a couple species that are typical here. By no means does it feel the same each day.

Well let’s talk specifics: who have you observed, and what are some of those surprising birds?

Every day this month we saw White-necked Jacobins, (Green) Crowned Woodnymphs, Fawn Breasted Brilliants, Green Crowned Brilliants, White-whiskered Hermits, and Purple-bibbed Whitetips. Even though they’re common for us here at RLT, they’re each rather stunning birds in plumage, size, and habits. Yesterday had some nice surprises: a male Booted Racket-tail came around a few times, a very small hummer with big white boots (made of rabbit fur, by the looks) and a relatively long motmot-type tail that ends in paddle-shaped feathers. Also, my only sighting of a female Violet-tailed Sylph was a delight (despite the female operating without that outrageous 8-inch violet tail that males wield). We also had one of only 4 viewings this month of a Brown Violetear. Not quite as infrequent (9 viewings in 29 days), but perhaps the most multi-colored visitor is the Velvet Purple Coronet—so regal in his (or her) purple robe and golden-coppery wings. Also, this coronet is endemic to the Choco-Andean ecosystem and I have a book that tells me it’s listed as “threatened” with extinction. So we’re always stoked to see it.

How do you feel about feeding these hummingbirds sugar water?

Dang, tough question. Are we supplying an artificial food source to wild birds? Yes. Does it create an “unnatural” environmental situation? Probably in this immediate area, in that the hummers do get accustomed to the red feeders and seem to organize social hierarchies to defend this “territory” and food source that we’ve manufactured. But to ask: are any species or individual hummingbirds somehow losing what it takes to make it in the wild, or does this intervention favor one species over another at the population level…? That seems doubtful to me. But RLT in part exists for researchers to pose such questions and develop field methods to test possible answers. Inquiries and Investigators welcome!

That said, it is flowering plants that we want our hummingbirds to be nourished by, so at RLT we see that interaction in the profusion of flowing plants right now in our protected forests, as well as in the handful of “hummingbird plants” that we’re propagating in the garden areas around our Lodge. Still, there is some self-serving-for-the-human-soul aspect of the hummingbird feeders, in that it brings us into very close relations with individual birds. For example, there’s a male Purple-bibbed Whitetip that greets us first thing in the morning, and will perch on the rim of my red coffee mug while I raise it to my lips. And there’s a female Green-crowned Brilliant that Anastasia rescued from inside the Lodge, that will perch close to the deck and chat something that sounds to me like appreciation and kinship conversation. So we do get to know these birds as individuals, thanks to the practice of giving them a sugar high and staring at them through binoculars for an hour each day. It’s great fun to share this with guests and volunteers—come visit, we do this every morning!

Speaking of the plant-and-hummingbird interactions, are there any final observations to share?

For sure. First, there are a handful of hummingbird species that I see around the Reserve, and which are almost never recorded in our daily feeder surveys. The Purple-throated Woodstar will buzz like a bumble bee up to the Verbena shrubs near our front deck most mornings, but we’ve never observed it at the feeders 20 meters away. The heart-achingly named Tawny-bellied Hermit is a striking bird from tip to tail, who I mostly see when I’m alone in the forest, looking up at a flowering epiphyte to notice her feeding naturally. Violet-tailed Sylphs favor the flowers of what I might commonly call a flowering maple, which we’re propagating around the perimeter of the gardens around the Lodge.

And I guess a highlight moment from this month occurred when I was hiking the Quetzals trail. As the trail climbs out of a dense forested area into a sunny zone where there is a grand patch of unusual red-stemmed shrubs (Malvaceae Werklea ferox), which towered 12 feet into the air with a profusion of large, bristly red flowers. Realizing I hadn’t seen this species of plant elsewhere on the Reserve, and appreciating catching it in full bloom (in morning sunlight, no less), I spotted a hummingbird that was new to me, feeding from flower to flower. With a short bill, glistening rosy throat and a distinct white crescent bib, I observed his behaviors closely at first, and while fumbling for my phone to snap a photo, I looked up and he was gone. Still, every time I walk through that patch of flowers now I wistfully hum a few bars from my 437th favorite Bob Dylan song, “You (Gorgeted Sun)Angel, You.”

~Jason Rainey, current co-manager/volunteer caretaker of Reserva Las Tangaras

Bienvenidos a Reserva Las Tangaras!

Yes, Welcome! That’s how we want all guests and volunteers at Las Tangaras Reserve (RLT) to feel upon arrival to our lodge, nature reserve and avian research field center, located “on the wild side” of the Nambillo River in the heart of Ecuador’s Andean-Choco’ rainforest. Certainly, we have felt very welcomed since arriving at the beginning of January for our 6-month tenure as volunteers tasked with managing the land and trails, coordinating projects and birding tours, and hosting our guests. After several intense and rewarding days getting trained up by our organization’s Director, Dr. Dusti Becker—and having her introduce us to our Ecuadorian neighbors, collaborators and companeros — we have taken the reins and after a few weeks it feels exciting to be leaning into the challenge. There’s much to learn in this wild, fecund and mega-diverse western slope of the Andes, right on that center line of the equatorial Neo-tropics. We’ve already made some progress we’ll share out here, but first allow us to introduce ourselves.

We are Anastasia “Tasia” Torres and Jason Rainey (aka Jaxson Lluveoso). Although well-travelled, we’re both Californians in origin and spirit, and took an expatriation leap last year, living, traveling and birding the past six months in Colombia (the only Rufous-Headed Pygmy Tyrants we want to experience are birds that call Andean cloud forests their home). We really have fallen for Colombia— it’s varied landscapes, people and avifauna—yet after visiting Mindo while attending the 2023 South American Birding Fair in October (Ecuador was the host country, and Mindo was the epicenter of the week-long event) circumstances had us excited by the prospect of applying ourselves fully with Reserva Las Tangaras.

Anastasia spent the first ten years of her adult life raising two sons on the wet-side of the Big Island of Hawaii, where she enjoyed homesteading and learning tropical gardening and fruit tree propagation—skills she’s eager to apply to the remnant banana and citrus orchards here at RLT. More recently, she worked in the field of sustainable energy, primarily in residential and commercial solar electricity; also very handy skills for RLT’s off-grid power! Tasia found her way to birds by taking a part-time second job helping a friend who owns and operates a retail store of the popular North American franchise “Wild Birds Unlimited.” At first, she was mostly skeptical and perplexed by her customers who would casually drop $100 on bird seed, and then chat to her with such admiration, devotion and detail about the Jays, Grosbeaks and Goldfinches in their backyard. But after some years of selling all manner of fancy feeders and bird seed blends, she used her staff discount to buy a pair of binoculars (and eventually an unrivaled and deluxe assortment of backyard bird feeders of her own!) and hasn’t looked back since. She’s only a few years into the hobby, but it’s gotten serious: she’s birded the western US, Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia and Ecuador. With Jason, she’s developing a Colombia- & Ecuador-based Bird Tourism, and Avian Conservation business (Tranquilo Birding, stay tuned!). With her previous experience leading Cooperative (shared-ownership) enterprises, and her current passion for bringing youth, women and other under-represented people into birdwatching and community-based conservation, Anastasia is currently serving on the Board of Directors for the international organization “The Birding Co-op.”

Jason was raised rural in the mountains of northern California, but got out to see the world and sample a very wide range of universities (too many countries and colleges to mention here!) in his 20s. After getting schooled in things like International Economic Development, Social Movement Organizing, Public and Non-profit Administration, Environmental Policy & Natural Resource Management, and Ecological Agriculture, Jason spent 15 years as a leader in three organizations. Most relevant to his role at RLT, he values the trail building, volunteer coordination, habitat restoration and water-quality and wildlife monitoring projects he developed and managed as the Program Director of the Marin (North Bay) Conservation Corps and then as the Executive Director at the South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL). And as Executive Director of the global NGO International Rivers…well, that role wasn’t so close to the ground so unless, for example, a Brazilian or Chinese energy company proposes a mega-dam on the Nambillo River that would flood the Mindo Valley…let’s say that grant writing and fundraising might be the most apropos skills to apply to RLT! In more recent years, Jason owned and operated an outdoor hospitality company, which offered high-end “glamping” and outdoor nature experiences at four locations throughout the Yuba Watershed of the west slope of the northern Sierra Nevada (California).

Jason’s been birding since 1999, when he was a graduate student (at IU-Bloomington) fascinated by the remnant hardwood forests of southern Indiana, introduced to him by his avid birding friend and accomplished global forest protector, Jim Ford. Anastasia relit his dormant passion for birds, and so…here we are at one of the world’s hands-down hottest birding spots, co-hosting and guiding guests in this avian paradise called Reserva Las Tangaras!

Our start at RLT has been grand. After training, we had one day to ready ourselves and the lodge for two groups: a pair of awesome volunteers from the US, Mo and Joli, who spent 5 nights and days pitching in on numerous projects, and a small group of 4 herp-enthusiasts who stayed a night checking out the various glass frogs and other nocturnal amphibians and reptiles living in the forests of RLT (the group was led by our friends at Ecuador Reptile Adventures).

In addition to teaching us how to play the board game Wingspan (which we’ve been traveling around with for over a year), Mo and Joli helped us with a range of habitat restoration and sustainability projects. Together we liberated from moss and encroaching secondary forest most of the banana and citrus trees in the remnant orchards around the lodge. Joli and Mo completed a full assessment of the experimental Aquacatillo (G, s) saplings that were planted on the Reserve in April 2022, mending protective cages and weeding and clearing around this important species in our habitat restoration project. (Aguacatillo trees produce fruits highly sought after by birds and mammals, especially the Andean “Spectacled” Bear. They are a large, slow-growing tree of excellent quality wood, that in decades past were almost entirely removed from the region, including the lands that are now protected by RLT.)

Mo and Joli also got trained in our avian monitoring protocols and woke before 5am to help with an early dawn project monitoring “our” Andean Cock-of-the-Rock lek. These boisterous and outrageously shaped birds have been coming to the same ridge of primary forest on RLT’s land twice a day, for at least 80 years; a dozen or more males shouting and screeching like geese, jostling for the “alpha” role and the reward of a quick courtship (if you will) with a female. Dr. Becker, with monitoring assistance from RLT managers like us, and volunteers like Mo and Joli, has been pioneering field research on these magnificent birds for nearly two decades. At RLT, we can lead guests on daily tours of this wonderous spectacle: if you’re visiting Ecuador, come join us and see for yourself!

We’ve otherwise been spending these first weeks at RLT familiarizing ourselves with the trails, trees, wildlife, watercourses, and birds of this exciting place and doing all we can to make any visitors to our remote lodge feel most welcomed, comfortable and well-cared for upon arrival. We’ve cleared and improved the entrance trail (Sendero Entrada) to our lodge and are flagging points of interest along the route and will construct a small rain shelter at the half-way point of this 2.2km (1-mile) trail, which is how most visitors reach RLT. The final 100 meters of the hike requires you to cross the Nambillo River by footbridge. We just finished some major improvements on the bridge (with a local expert), adding new cables and re-anchoring footings in more concrete reinforcements: it’s still exhilarating to cross over to our lodge on the wild side of the river (Torrent Duck, White-capped Dipper, and Striated Heron can be seen from the bridge), but much sturdier than in the past. And Anastasia, who is an experienced and accomplished cook, has been enjoying putting together tasty, wholesome meals for our volunteers and guests.

And finally, to address a broader question that might be on the minds of those paying attention to current events in Ecuador: The recent and dramatic episodes of drug cartel violence (after a prision-escape early in January) in the south (Guayaquil) and coast of the country has put Ecuador in the international news in an unflattering light. From our experience traveling within Quito and to-and-from Mindo (which we’ve done several times, without reservation, since the President’s decree of late-night curfew) we notice almost no difference and feel quite safe and secure. The glorious shopping malls of Quito are still filled with people young and old; all the buses are running their normal schedules without the inconveniences of security checks, and certainly the charming little hamlet of Mindo continues to bustle with travelers from Europe, North America and Asia arriving every day to this mecca of biodiversity, with scores of well-established nature tourism opportunities all open and operating. If you’re considering a trip to Ecuador in the coming weeks or months do your own research–but count us among those who think you should still come and visit! We’d be delighted to help you put Reserve Las Tangaras in your itinerary: with our network of local service providers, we can offer advice or arrange your trip, starting from your arrival at the Quito airport, if you’d like. Contact us and let us know what you’re most interest in doing and seeing. We look forward to opening up the Las Tangaras Lodge to you and offering a warm beverage and a hearty “Bienvenidos”!

Jason & Anastasia

Nine Months Out

We wake up to a unique chorus every morning. Maybe the combination is Red-faced Spinetail plus Yellow-throated Toucan. Or perhaps Scaled Antpitta plus Zeledon’s Antbird plus Brown Violetear. Plus 30 others, of course. There are so many birds here that every dawn may sound a bit different out of the same window. Then we rise and look out of that window – at a misty mountain forest draped in various shades of green with red, pink, and yellow highlights. Bizarrely shaped inflorescences peek from behind mossy trunks, often so strange and waxy looking that they seem fake. Then, out of nowhere, a Violet-tailed Sylph flashes up and sticks its face into one of those fake-looking flowers, waving its elegant tail around for balance. Always the river roars in the background. There’s no doubt this place is some kind of wonderland.

Yet, we’re ready to leave. It’s time, not only because our contract is ending, but also because our time out (a term that has new meaning now) has made it painfully obvious what we really want from our life. Emily and I had both bounced around in seasonal jobs a fair bit in the past, but by the time we applied to come to Las Tangaras, we were both sitting comfortably in permanent, “real jobs.” Maybe that scared us. Or maybe we knew that we just needed one last big adventure before we could relax into a steady life. Whatever the motivation, we applied. After getting the offer, we then applied for technician positions in Panama to fill the time before coming here. By now, we’ve been away from the US for 9 months. It’ll be nearly 10 by the time our plane lands back in Washington, D.C. While it’s not true that we wouldn’t change anything about our year, we can confidently say that we feel blessed to be here, having learned what we’ve learned and had a chance to live this way out here in the cloud forest.

Even though we’ve been gone for 9 months, we haven’t actually travelled much. Besides a few weeks of exploring Panama, most of our time has been spent simply living. Here, in a sense, our job is to inhabit this place. A lived-in house is a house that (hopefully) isn’t falling down. Especially here, in a wooden cabin in an environment that’s hell-bent on eating wood 24/7, someone’s got to be here. We also have grounds to maintain, a lodge to run, and a whole bunch of other small tasks, but the point is that we’re pretty dug in. Maybe that fact has made it obvious that “dug in” is exactly what we want to be. We’ve scratched the Big Adventure itch, and now we’re ready to find a place where we intend to stay – to dig in without the knowledge that, pretty soon, we’ll have to dig back out.

Without digging in, at least for us, life feels pretty pointless. Not that travel isn’t fun and mind-expanding, but lasting relationships – both with people and places – come from sticking around. Life-enhancing projects are also ruined by excessive movement. Not three days after we got here, I mixed up a brand-new sourdough starter. My last loaf in Ecuador came out of the oven this morning. I’ve also fermented some kraut and ginger beer. But we don’t have the capacity to do much more than that here. Our limitations make us dream of what we can do when we find a place to dig in. Chickens, bees, mead, goats and/or sheep, a lasting garden, canning – the possibilities are endless.

Thankfully, we know we’ll be leaving the reserve in capable hands. At the 2023 South American Bird Fair, which happened to be in Mindo, we met a great couple currently living in Colombia. We spent the better part of a day with them and got to know them a bit. We had no idea that one month later, we’d be told that they applied to be the new reserve managers and were offered the position! We think they’ll do a great job, and we can’t wait to keep reading the blog to see what they’re up to in the first half of 2024.

As for us, we’ll hopefully be home during that time, wherever that winds up being. We’ll continue to study the world around us, but with a new appreciation for how big and strange it really is, and how lucky we are to have the chance to make something nice out of some small part of it.

Birding the Reserve: Our Experience So Far

Our time here is coming to a close. We know from experience how quickly a month can pass by – even if it only seems that way in the rearview mirror. We feel fortunate to be here, partly for the perspective that living abroad can yield.

Pursuing naturalism evolves our perception of the world in a paradoxical way. The more we strive to learn about the organisms and natural cycles around us, the more our curiosity expands both inward and outward. We want to dig deeper to understand our home territory, yet we also imagine what there is to see if we just hop in our cars and drive to another state – or hop on a plane and fly to another continent. The result is a duel between opposite desires – one for depth of knowledge and the other breadth. Emily and I had traveled as much as we reasonably could before coming here, following our curiosity outward, expanding our breadth of knowledge. But it’s undeniable that our deepest understanding of the natural world resides in the southern Appalachian Mountains.

The deeper we dig to understand our home region, the more comfortable we feel in our environment. At this point, we feel quite comfortable in the Appalachians. We can walk around and recognize just about every bird we’re likely to see on any given day, though we do need to brush up before migration hits. The same goes for trees (minus the migration part) and many herbaceous plants and mushrooms. We also have knowledge of which of those plants and mushrooms are edible, medicinal, what to use them for, when to look for them or harvest them, etc. We know many people, some of them good friends, that take birding to another level, obsessing over it almost as a religion. They are very talented, dedicated people. We will never be quite that way, though we are quite competent as birders. The point for us, rather, is that we can look around outside with a deep sense of familiarity that’s difficult to come by without naturalistic study. We lived in a world we knew.

When we came to the reserve, we found ourselves in a new world. We no longer had that familiarity to lean on. Every tree, every mushroom, just about every bird was unknown. And, being in the tropics, there were about a zillion more species. We’d sit down on the porch to start the day’s hummingbird survey, watching a cloud of iridescent smudge marks zipping around the feeders, then perching there looking like airborne seahorses. Meanwhile, a mixed species flock would appear, suddenly filling the trees outside with chipping, flitting birds of various sizes. Blues, blacks, browns, yellows, and greens would flash between the leaves, trailing unfamiliar songs. A few minutes later, they’d be gone, and we would have only truly seen a handful of them. There was a lot to learn.

Opening up a field guide to a tropical region is intimidating. Flipping through Helm Field Guides’s Birds of Ecuador is reminiscent of scrolling through color palettes. Pages go by in gradients – white turns to gray turns to black turns to brown turns to purple, and eventually you’re looking at the bright greens and blues of tanagers and parrots and quetzals. The most difficult ones to learn, though, are the ones that only birders travel to see: foliage-gleaners, spinetails, woodcreepers, treehunters, flycatchers. Brown birds, gray birds, buffy birds. A few are obvious, but mostly the differences range from small to minute. This woodcreeper has a slightly paler lower mandible than that one, which has a slightly streakier belly than that other one. Or the first clue might be behavioral. A small brown bird with a medium-length tail and a short, stout, slightly upturned bill is scooting around in a tree. You figure it’s either a little Wedge billed Woodcreeper or a Plain Xenops. Probably you can squint a little harder and notice the crisp white mustache mark or the lack of supporting barbs at the ends of the tail feathers, but maybe it’s flown away before that’s possible. It doesn’t matter, because you noticed that it wasn’t pulling itself along up the trunk of the tree, but rather clambering around branches like an acrobat, flicking off bits of bark. You know it was a xenops.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Merlin Bird ID app has made things a whole lot easier, too. We no longer have to sort through the range maps of seventeen pages of furnariids to narrow down our options. And we may turn to the guidebook for further reference or a wider range of options to look through, but we don’t need to debate whether we want to bring into the field for a day of birding. Having Merlin on our phones lets us keep a manageable list of potential birds right in our pockets, and one with which we can search, query, and even listen to recordings of songs and calls. I’m generally resistant to this sort of advantage, feeling that the removal of effort from the process of learning does existential harm, but I have to admit that I love the Merlin app. It doesn’t remove all of the effort from learning the birds – if it did, we’d know them all by now, and we certainly don’t – but it does make it more manageable.

There’s an important distinction between ‘ability and ‘capability.’ ‘Ability’ is when you have the knowledge and skills to do a thing. ‘Capability’ is when you have the potential to gain that knowledge and those skills. Coming here and learning what we’ve learned has made me feel more capable as a naturalist. Having always loved nature and animals, my knowledge of the flora and fauna in the United States grew out of a natural curiosity over the course of many years. It was a slow build, knowledge piling up on knowledge, so that by the time we left for Central and South America, I don’t know that I had ever fully appreciated it. I’d forgotten what it was to be in the dark. Learning the birds from scratch has been a humbling experience.

The natural phenomena we have here to see and observe are truly amazing. From the feathered tongues of toucans to the aerobatics of hummingbirds to the dragon-like shrieks of the cocks-of-the-rock, the more you look, the more you notice. Scrutiny is rewarded with further details. In four and a half months, we’ve barely scratched the surface. A local came as a favor a couple of weeks ago to teach us some trees. He taught us about 20 species – there are probably at least 500 in the region. Just a scratch.

The rain is coming back strong. October has been wet. We’ve been able to notice not just an increase in humidity, but also an increase in the diversity of insects around us. Leafhoppers, katydids, weevils. There are endless beetles, often seeming to exist in sets of similar styles. We typically don’t try to identify them; we look at them more like art, like we’re browsing through a gallery. The moods and personalities of the beetles are open to interpretation. We don’t need to know their names. In a way, maybe that’s part of the shift in perspective that we’ve received. The boost in both confidence and humility in the face of a new constellation of life have brought not only an increased ability to quickly adjust to a that new constellation but also greater willingness to just appreciate it without expectation of understanding. Wherever it came from, life is art. Personally, I look forward to appreciating it, wherever we are.

No Fridge? No Problem!

As Emily and I think about what is different about living here, several obvious things come to mind. We’re sitting almost directly on top of the equator, so day length doesn’t change. Instead of colder seasons and warmer seasons, we have wet seasons and dry seasons. Instead of one species of hummingbird, we have a suite of fifteen or so that we may expect to see on any given day – more if we’re lucky. Yet, one of the biggest aspects of life here that stands out to us is something very simple, which until recent times would be completely normal anywhere in the world: we have no refrigerator.

It’s been instructive. It makes us realize how many of the foods that we put in the fridge don’t need to be there. It turns out that most leftovers can sit out for a couple of days before they start to go bad. Most sauces don’t need to be refrigerated at all, nor do eggs or most vegetables or fruits if you eat them within a week or so. Not that we store most fruits and veggies in the fridge under normal circumstances, but foods often shuffle around, so it’s not unusual. Cheeses like mozzarella can happily sit wrapped up for a few days in cool water. That leaves milk and meat, and we do miss those. Our milk is powdered. “Leche en Polvo.” You get used to it. As for meat, we typically buy enough for a meal with leftovers when we go to town, so we get to eat it maybe two days per week. Eggs and beans fill in the protein gaps. Do we miss our refrigerator and chest freezer back home? Yes. But it’s good to know that life isn’t terribly inconvenient without them.

I mentioned in a previous post that I enjoy fermenting foods and drinks. Sauerkraut, mead, beer, sourdough bread, and kombucha are all things that I’ve fermented on a regular basis back in the states. Generally, the historical purpose of intentionally fermenting foods has been to preserve them. It’s useful for storing nutrient-rich foods over the colder months, but it’s also useful for saving bumper crops. That’s why cabbage is the traditional vegetable used for sauerkraut – it all comes in at once. Without a refrigerator and/or freezer – or a pressure canner – you either lose most of it, or you ferment it.

We got to experience a much smaller version of that after the banding workshop last month. The group left behind a large cabbage and a pile of little rosy radishes. That doesn’t sound like much, but for two small people that aren’t interested in a single individual cruciferous vegetable and its spicy cousins dominating several meals in a row, it presented a choice: ferment it or lose it. Now, weeks later, those veggies are still around, shredded and steeped in their own now acidic juices. We eat the kraut here and there – on eggs, in soup, maybe mix things up and put it on pasta. I don’t necessarily recommend doing that, but hey, experimentation is key here. Actually, that’s part of what makes fermentation so fun: experimentation. Traditionally, sauerkraut is fermented cabbage, but as you just read, we did it with radishes mixed in. Many vegetables ferment quite well. I’ve made kraut with carrots, turnips, kale, green beans, peppers, kohlrabi, even spaghetti squash. Cabbage is almost always at least half of the mix, but it doesn’t have to be in there at all. Every time I see a vegetable I haven’t thought much about, it’s hard not to think, “I bet I can ferment that.”

The experiments don’t end with vegetables. Around the end of August, I made a ginger beer. All it took was to boil some chopped ginger, let it cool until warm, dissolve a load of sugar into it, sprinkle on some bread yeast, and pour it into sterilized jars. I’m simplifying things a little bit, but not much. A few days later: boom, we had a tasty alcoholic beverage. The next week, I did it again but added pineapple. Use that as the base for a cocktail with rum and lime juice, and bam, you’ve got a Mindo Mule. Last week, I used beets instead of pineapple and added fresh basil during the fermentation. The result was a richly colored, nutritious brew that would make a Shrute proud (if you haven’t seen “The Office” you wouldn’t understand). Beets are well-demonstrated to be uniquely beneficial for the cardiovascular system. Too, the unfiltered “beer” is filled with B vitamins produced by the yeast as they bubble away. What’s the harm if we happen also to catch a buzz off of such a medicinal homebrew?

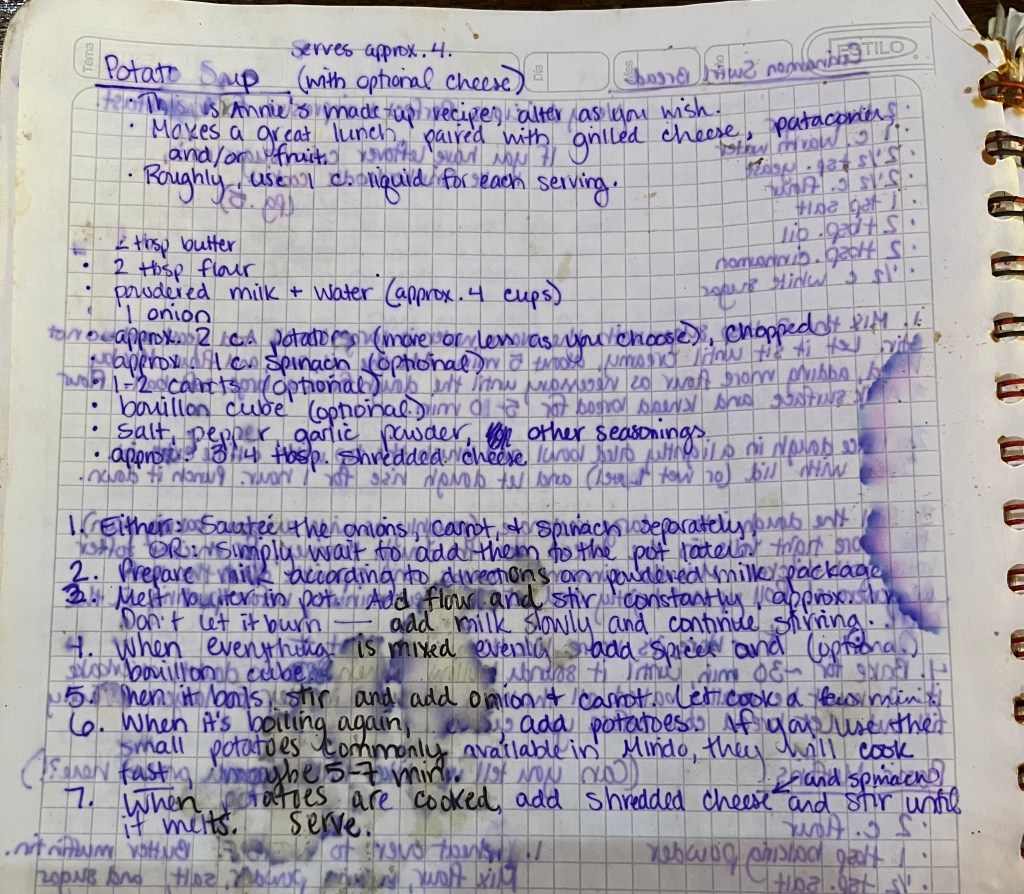

Of course, not everything we consume is fermented. Normally, Emily and I are far from vegetarian, so our diet has shifted quite a bit since coming to Ecuador. That also means we’ve had to develop a new rotation of meals to cook. We’ve taken to frequent meals of coconut curry, Pad Thai, fajitas, chili, and lots of scrambled eggs with vegetables, often served with Emily’s “zucchini patties.” Other meals and desserts have come out of the Managers’ Cookbook, created by past managers, and updated over time. The humble potato soup has been a winner; multiple guests have asked for the recipe. We like to add black-eyed peas and cabbage and/or kraut for more substance and variety.

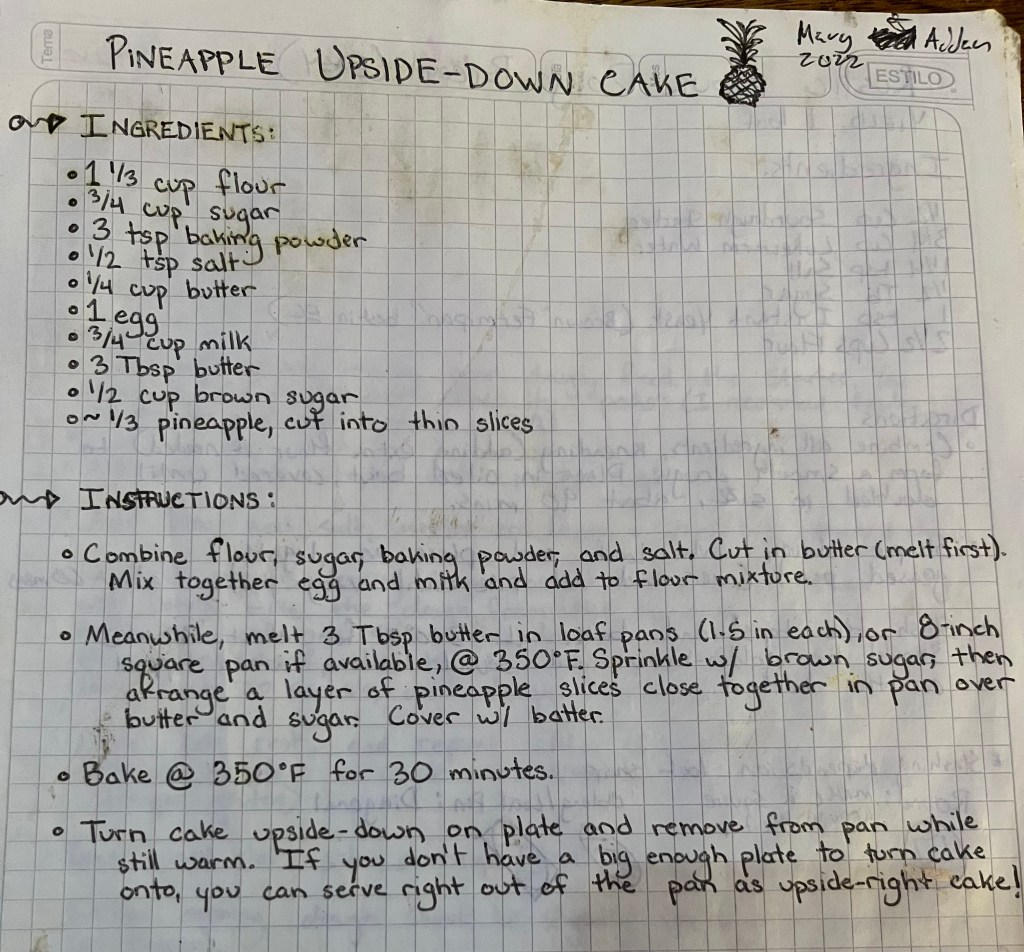

We also really like the pineapple upside-down cake, which Emily has modified by adding little pieces of pineapple to the batter itself. That makes it even more moist. Just don’t overdo it or it won’t bake properly.

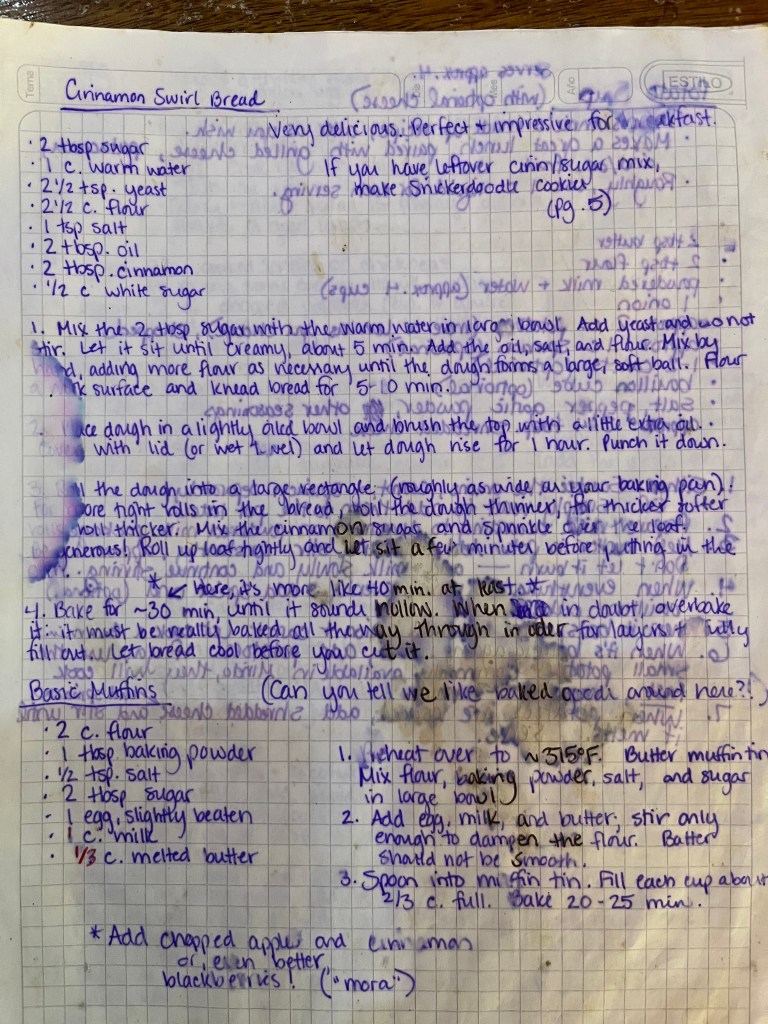

Another popular recipe that we’ve shared with guests is the “Cinnamon Swirl Bread.” We like rolls better though, so we cut it into four cross-sections and bake it like that. Emily likes to add cubed apples and sometimes a bit of anise to the cinnamon sugar mix.

As you can see, there’s more to life at Reserva Las Tangaras than hummingbirds and rain. As we go into our last two months here, we look forward to further exploring the cookbook of our predecessors, and maybe adding to it ourselves. We hope this peek into our kitchen has given you something new to explore as well.

Remember to Forget

There seem to be certain fundamentals to happiness which, at least in my experience, need to be realized over and over again. We tend to lead hectic lives, so it follows that we forget these fundamentals from time to time. And when I say “happiness,” I’m not talking about some vague concept of getting all of the things you want in life. I’m talking about a mental calm in which you’re perfectly content with whatever happens to be occurring at the moment. It’s wanting what you have, rather than having what you want. Of course, this is not an original thought. If it were, it wouldn’t be very fundamental. Also not surprising is that as time goes on and technology advances, it becomes more challenging to find situations in which those fundamentals are easily remembered. If such a situation exists, surely it should be at an off-grid cabin in the mountains of Ecuador. It turns out, though, that where there’s a smart phone, there’s a way.

The concept I’ll discuss here has been gnawing at me for a long time. Its image in my head, and sometimes in crude diagrams, has gone through various phases in my effort to appropriately capture all of its elements in one metaphor. I still don’t think I’ve done that, though this may be the closest I’ve come. I should also say that I’m under no illusions that this is a groundbreaking idea, or that it’s difficult to understand. It just takes some space to lay out in its entirety. Likely, others have already neatly figured it out. As the saying goes: Everyone is the unconscious proponent of some philosopher.

Most recently, my thoughts on this topic have been reignited by the August 2023 bird banding workshop here at the reserve. This is a two-week event that we have here twice per year – once in the winter (the wet season) and once in the summer (the dry season). Participants come out to gain experience, either for personal or professional reasons, with mist-netting and banding birds. Emily and I were fortunate to be able to be a part of it, and to get to know a very cool group of people from around the U.S., as well as a warm group of Ecuadorians who come to help run each workshop. We had the opportunity to handle and band some unique birds, and to solidify and expand our identification skills.

What sparked this post, however, was something in the background of all of that: silence. As I said before, one would think that excessive distraction by technology would be a small concern here – to be sure, it’s far easier to manage here than back home. But smart phones are amazing devices capable of storing huge amounts of content. Since the events of the last few years, Emily and I have been pretty plugged in. Mostly, we listen to a lot of podcasts – and there’s a lot to listen to. Besides shows concerning current events, we like to keep up with shows about science, history, and anything that interests us. There’s always more to learn. I think we both expected that we would be forced to take a couple of steps back from all of that during our time here, but that hasn’t been the case. We can download the latest episodes when we have cell service about twice per week, and we still don’t make it through everything new. The thing about something like a two-week banding workshop, though, is that it demands that you disconnect from your normal routine and fully drop into your current situation. That means that keeping up with the latest episodes – or any episodes – of your favorite podcasts isn’t really an option. The result: the restoration of a sustained inner calm that I haven’t felt for some time.

Before I dive into the analogy, I should say that I don’t expect everyone will relate to this. It seems to be a problem of a certain set of personality types. Emily, for instance, isn’t afflicted by this. I think the underlying principle may be universal, but the abuse of the machine is not. Only some abuse the machine.

Picture the mind as a biological cell. (That’s the “machine” which I just mentioned.) It’s sitting in a medium of information – sounds, colors, wind, temperature – everything in the outside world. Right now, for instance, the medium in which my cell sits consists of a light breeze, swaying banana leaves, the agitated song of a Red-faced Spinetail, a large bee steadily descending through the air while staring at a tree, etc. Inside the cell are thoughts, feelings, ideas, and quite possibly an infinity of indefinable bits that make up human consciousness. We can think of these bits, together, as a kind of cerebral SCOBY – a Symbiotic Community of Bacteria and Yeast.

The cell membrane, as the cell floats within its medium, is acted upon by two opposite pressures – pressure pushing inward from the medium, and pressure pushing outward from within. The pressure pushing inward fluctuates according to the amount and power of the stimulation coming from the outside world. A quiet forest at midday (when there is very little animal activity) exerts little pressure. A dense podcast about the biochemical actions of a medicinal plant exerts great pressure. Pressure from the inside is generated by fermentation. That is, the cerebral SCOBY ferments information which makes it through the cell membrane from the outside. Think of information like nutrients for your SCOBY. It takes them and uses them to grow and reproduce, at the same time producing waste – a cerebral gas, much like the carbon dioxide waste produced by an actual SCOBY.* Thus, this exerts an outward pressure.

Now we have a picture of a cell in a medium, with pressure pushing both in and out, and we understand the source of each pressure. What we’re missing is the moderator; what regulates the membrane’s response to these two pressures? The answer is focus. Just like a real cell membrane, our metaphorical cell membrane is semipermeable, meaning it can selectively allow things to pass through it by actively transporting them from one side to the other through channels. We’ll call those active channels. It also has passive channels, through with information passes without effort, or even consent. More on that later. The active transport of information across the active channels is regulated by focus. When we focus on something, we are selecting that thing to cross into our cell. For example, we may focus on that podcast about plant medicine and, in doing so, select various pieces – likely as many as we can – of biochemical and natural history information to travel across the membrane and enter our cell.

While we are focused, fermentation activity by our SCOBY decreases. We are adding information to be fermented, but the fermentation can’t start until our focus on the outside medium subsides. Because fermentation slows while we are focused, inward pressure pushing out decreases. Meanwhile, the pressure pushing in has actually increased, which is the very reason we are busy focusing. In response, the cell shrinks, leaving less room inside for more information to enter. The longer we focus, the smaller the cell shrinks, the less room inside. Eventually, after a long period of focus, there’s no room left, and continued focus is impossible. This is part of what happens when you pull an all-nighter to complete important work. As soon as focus ceases, fermentation recommences, and the cell begins to expand again, allowing for new ideas to grow as SCOBY activity ramps up and the available space increases.

With this model in mind, it’s easy to imagine how spending too much time in a state of focus can hobble our minds. With no time allocated to fermentation, the cell remains shriveled, unable to grow. Without considering mental health, one might focus until the cell is shriveled like a raisin, relax just long enough for it to expand a hair, and then start focusing again. More personally, by mechanically trying to fill every unfilled moment with increased stimulation and forcing my mind into a state of focus, I was stunting my mind’s fermentation. The banding workshop forced me back to baseline by removing the option to fill those moments.

The three of you who are still reading may be wondering, “But if you never focus, wouldn’t the SCOBY eventually run out of food, and fermentation would stop? Then, the cell would collapse!” True, but remember that I promised to return to the passive component of the membrane’s permeability. If we picture that when the cell fully expands, its membrane stretches, and every part of its surface becomes exposed, while the opposite happens when it deflates, then this will make perfect sense. Information will always make it through these passive channels, whether we want it to or not. But consider focus as an action which flexes the membrane, opening the active, selective channels, while pinching shut the passive ones. Thus, the act of focusing reduces the amount of information which is passively received into the cell. Also affecting this is the degree of inflation or deflation of the cell at any given moment. As I alluded to above, a more inflated cell will have more passive channels open to transport information. Considering all of this, it follows that a state of ‘unfocus’ both keeps passive channels open and exposes more of them, while a state of focus does the opposite. Thus, and unfocused mind still receives information for the SCOBY to ferment, it’s just that much less of it is intentionally accrued.

The moral of the story isn’t that being focused leads to unhappiness, and we should never do it. Rather, to those of us prone to insisting on always focusing – on having a task, a goal, an object for our attention – we’ll do well to realize that our SCOBYs need room to grow. It’s okay to have a smart phone in the cloud forest. But sometimes, for our own sanity, we also need to remember to forget it.

* It’s also fun to think about how we can extend the analogy in thinking about that gaseous “waste.” In a real fermentation – like in beer – that carbon dioxide waste exerts ancillary effects on the primary product (the alcohol). A flat beer is no fun; carbonation is what gives it it’s liveliness. Plus, it affects the way the alcohol is absorbed in your body (a good or a bad thing, depending on your stance on alcohol). Similarly, the “waste” gases that our cerebral SCOBYs produce (spontaneous but unrealistic ideas and daydreams are good examples) add liveliness to our minds, and affect how we process information down the road.

Waterfall Plunges and Tours for DJs

Finally, we saw his flashlight appear on the other side of the bridge. On WhatsApp, he’d referred to it as a “torch,” so I expected he’d be from the U.K. The torch paused for several seconds before slowly floating across the river. It was 5:51 A.M., meaning he was half an hour late. The sky was fading from black to gray, and the birds would be starting in a few minutes. This “Mark” guy better have a good story to tell, I thought.

It was an inauspicious start to our first Andean Cock-of-the-Rock tour as managers of the reserve, and we didn’t yet understand that that was mostly our fault. Thankfully, though, as our guest bobbed into view at the terminus of the entrance trail, our anxiety melted away. He looked happy as could be with his big smile and his black KISS ballcap atop his bald head dripping with sweat. We could tell immediately that this was a nice guy and that this would be a good morning after all. And, as it turned out, Mark did have a good story to tell. It involved lots of confusion regarding wrong turns, walking ten minutes off-trail up a ravine, heeding large letters reading “PROPRIEDAD PRIVADA NO INGRESAR” and turning around, and many texts which we didn’t receive until later. “I’ve come to the water with wood boards,” one read, “Do I walk in the boards over the water. I tried crossing but no trail?” Another pair of texts, soon after, asked, “Can’t find trail. Did I go too far?” He must have been up the ravine about then.

The situation precipitated from three factors: 1) Mark got dropped off at the wrong gate, about 40 meters from the right gate – enough to make the difference before first light, 2) he was not used to walking in the dark down long, strange trails with many twists and foreboding signs in a foreign language, and 3) we didn’t properly consider that fact and failed to provide enough details in our directions. It’s a good thing he started his journey extra early that morning, because, as far as we can tell, he walked most of the way down the trail, then all the way back up, and still somehow managed to get to the lodge only half an hour late. Frankly, we don’t understand how he got here, which is mainly because he didn’t understand how he got here. But by the time we’d shaken hands, it didn’t matter. Up we went to the lek, and Mark’s unflappable cheerfulness and excellent conversational skills ensured a good time for all.

We’re Keiran and Emily, the newest managers here at the reserve. Emily grew up on a farm in southwestern Virginia and as a child vowed to never have an outdoor job (which has since been broken many times over). Going into college, she wanted to be a pharmacist, but that quickly changed by the second semester when she decided to switch over to wildlife conservation. Throughout the rest of her time at Virginia Tech, she learned more about the nature she was surrounded by growing up, and decided it wasn’t so bad after all. Upon graduation, like most of our peers, she took seasonal jobs across the country in Oregon, Texas, Georgia, and Idaho before settling into a full time biologist position in West Virginia. After about 6 months, she got the wanderlust urge again and convinced me to apply for this position – not that I took much convincing. So here we are, now 5 months into our 9-month big journey. While we’re here Emily is most excited for the birds, but is also interested in the diversity of insects (excluding mosquitoes) and orchids, and is looking forward to experimental baking and reading.

I also grew up in Virginia, but on the coast. And, unlike Emily, I always knew I wanted to work outside, somehow. Sure, I spent my share of hours in front of computers and Gameboys playing video games – we all did. But I also ran around the woods barefoot and went frog-catching in the creeks with my friends. I even got scabies – a (marginally) nicer name for mange – as a child from spending too much time chasing fiddler crabs through the tidal mud. As time went on, other aspects of nature became more interesting – edible and medicinal plants and mushrooms, hunting and fishing, the relationship between natural living and health. Varied interests have led to varied work, from bat and honeybee research in Virginia to habitat restoration in the Great Basin to, now, nature reserve stewardship in the cloud forest. Living here, I’m most excited about learning a whole new set of fauna and flora, continuing to ferment various foods, experiencing what it’s really like to live off-grid, and taking advantage of the free, daily cold plunge that is the river in our front yard.

Emily and I have lived on the reserve for six weeks now. One might think that time would move slowly at an off-grid wilderness lodge. There’s no wifi, no TV, no trivia night. Frankly, though, we can hardly believe it’s already been this long. This place keeps you on your toes. There’s a lawn and trail system to keep up with, a house to clean and wax, an outhouse to renovate, bird surveys to do, a water system to maintain, plus hospitality duties when we have visitors. And of course somebody has to swim in that river and read all of these books in the reserve library, so that falls on us as well. It’s madness.

We often reflect on how strange our life is. We know exactly where our water comes from. In fact, about once per week, I find myself in my birthday suit under a frigid waterfall far above the lodge wrestling with a heavy rock wired to a hose. The next morning might find us examining multiple sets of puma tracks just out the back door, or maybe leading a tour for an intrepid DJ from Los Angeles named Mark (not a Brit, it turned out) to see a bird with about the silliest name one could imagine a bird to have.

Such is life here at Reserva las Tangaras. Come on by for a cinnamon roll or some fresh sourdough. We promise the water goes through a filter before it gets to the kitchen!

Summer comes and we leave

Our time is ending here just as the rainy season is drying up and summer is arriving. For the second time in our whole stay here, we got to witness the afternoon sun in its full glory. The golden-yellow light softly filtered through the canopy, revealing a new palette of greens we had yet to see. The rain has finally stopped and the river now runs crystalline blue, turning almost turquoise under the midday light. It has been a special gift to see the reserve in a new light as we wrap up our final month here.

The forest is full of flowers; so full, that the hummingbirds have almost completely stopped visiting the feeders except for a few White-Necked Jacobins, Green Crowned-Brilliants, and Brown Violetears. The chaos of the near 15 species we would survey everyday has now dropped to almost four. The Flor de Mayo, a flower that grows high up in the trees ranging from an imperceptible lavender to a soft glowing pink has begun to fall and decorate the forest floor. Meanwhile, other shades of purple, orange and red, dot the forest; a myriad of flowers that remain a mystery to us. The forest here is so diverse in vegetation, plant identification was a challenge that eluded us up until the final day.

In May, we began putting bananas out on the feeders every morning. For weeks we had no visitors, except for a wily Tayra who would eat all of the bananas we had carried down the road in our heavy packs in minutes. Nonetheless, we kept our hopes up. Slowly but surely a pair of Palm Tanagers began to hesitantly come to the feeder in the back-yard. Maybe they told their friends or maybe the alluring yellow bananas drew them in, but more and more species began to come. In our last week, I saw my favorite bird, the Orange-billed Sparrow on the far feeder. I was delighted. We are passing off this project to Kieran and Emily, the new managers, and hope the fruits of our labor continue to bring more and more bird species to the yard around the cabin.

Arriving here, we new very little about birds, and even less about tropical birds. In our last month, we began to take note of how many calls we recognize and species we can identify upon first glance. We never reached our goal of identifying 150 species in one month, but we learned a lot, and are leaving with a new found appreciation for the breath-taking beauty and diversity of birds that populate the Andean Cloud-Forest.

One last gift from the forest

Towards the end of our time, we had a very special encounter with one of the most iconic species of the Andes. A visitor came to do a bird tour with us, and it was a beautiful sunny day. After seeing several species of tanagers, becards, and woodpeckers, we made our way over to the Club-winged Manakin lek to show her this amazing species. Hattie heard a loud crash, and muttered about it maybe being the bear, half joking. I shrugged it off, thinking it was a deer that we’d seen recently, but decided to check it out anyways.

We could hear it moving, slowly but steadily, and not so quietly. It seemed to be knocking into all the branches in its way, and we all got a glimmer of hope that maybe Hattie had been right. The thick vegetation of secondary forest regrowth blocked all attempts to see it, but the animal continued through the forest conveniently close to the path leading to the third observation point. We all walked as quiet as we could, although I cursed myself under my breath for snapping far too many branches along the way.

At one point, Hattie moved ahead of me on the trail. I thought I heard a sound off to the right, but Hattie seemed to know where it came from. They crept forward slowly, then rapidly turned around looking at us and said “It’s a bear.” Melanie and I looked up into the trees and saw a bristly black coat rapidly scaling the moss-covered trunk, hiding itself away in the vines and leaves. Only a small snout peaked out.

As soon as we realized what it was we had been following, we all quickly backed up until we were in a much more comfortable range of the bear so to not disturb it any more than we already had. It watched us and we watched it in return, both cautious but neither wanting harm to come of the others. I later read that Andean Spectacled Bears are extremely docile compared to other bear species. Of course, with any large mammal, it is extremely important to keep a safe distance and not agitate them, so after watching for a couple minutes and snapping a couple photos, we left the bear to its business. Trying to pay attention to the manakins after that was almost impossible. A sense of profound wonder grew inside me. For months we had dreamed about getting to see it wandering through the dense forests across the reserve, but to no avail. We saw no tracks, and it never appeared on our camera traps. Yet this day, and it is a memory I will never forget, we had a rare encounter with a frequently arboreal, cloud forest dwelling bear. It was truly an incredible way to finish off our time here.

-Logan and Hattie