A Hummer of a Q & A

Even in the short month of February, so much can happen out here at Reserva Las Tangaras. We’ve gotten into good rhythms to keep the Lodge well-maintained and provisioned, to know when to rest the machete arm after a morning of trail clearing, and we’re noticing patterns as we observe, monitor and count birds. We’ve also found time to search for monkeys, learn some frog songs, and explore this incredible rain forest Reserve with our guests. It’s difficult to choose which observations and stories to share out…yet our daily practice of an hour of hummingbird monitoring has been rewarding and a joy to share with our visitors and volunteers. We’re not experts, but here are responses to the many questions that arise when we gather on the deck to observe the hummingbirds here at RLT.

So what’s going on with the hummingbird feeders?

Everyday we thoroughly clean up to ten feeders and fill them with 1:4 sugar water. Anastasia’s been the lead on hummingbird care, usually done with the whole process with feeders placed on the far perimeter of yard and gardens before the first cup of coffee is brewed. We’re wanting to create an ideal environment around the Lodge for hummingbirds, and for their human observers. The feeders are a small, but important, part of that. Plus, it allows us to build upon a long-standing baseline of data on daily hummingbird abundance at RLT.

What do you record on that data sheet?

We remove all the hummingbird feeders on the property, except for 3 that we’ll concentrate in one viewing area. Then, for 60 minutes we take note and tally every individual hummingbird that visits the feeders or is otherwise seen “in the observation arena.” For birds that have sexual dimorphism, we take note of females and males observed, too.

How do you differentiate between “individual” birds?

A few ways. Of course, first we have to identify the species, and sex of the bird (if observable). Then, we’ll count more than one individual if and only if (1) we see more than one bird at the same moment; (2) we’ve familiarized ourselves with distinctive markings on a particular bird—which is easier to do with some species over others; and (3) perhaps an individual of a species will have a golden marking from pollen on a given day, but her “sibling” won’t…which helps us to affirm for example two female Green Crowned Brilliants. Fourth, some of the hummingbirds wear tiny anklets that help us track at the individual level! So, we’re cautious not to double-count any bird, and thus our data are conservative and give the minimum number of birds observed.

On average, how many hummingbirds do visit the feeders over the course of an hour?

Let’s look at yesterday’s data (Feb 28th)—over the course of the hour we observed 12 different hummingbird species, half of which can be visually differentiated between females and males. So, tallying up the marks on the data sheet, we observed a minimum of 26 individuals at the feeders or in the arena. That’s about average for any given day of this month, however we saw some nice birds yesterday, yet also didn’t get visits from a couple species that are typical here. By no means does it feel the same each day.

Well let’s talk specifics: who have you observed, and what are some of those surprising birds?

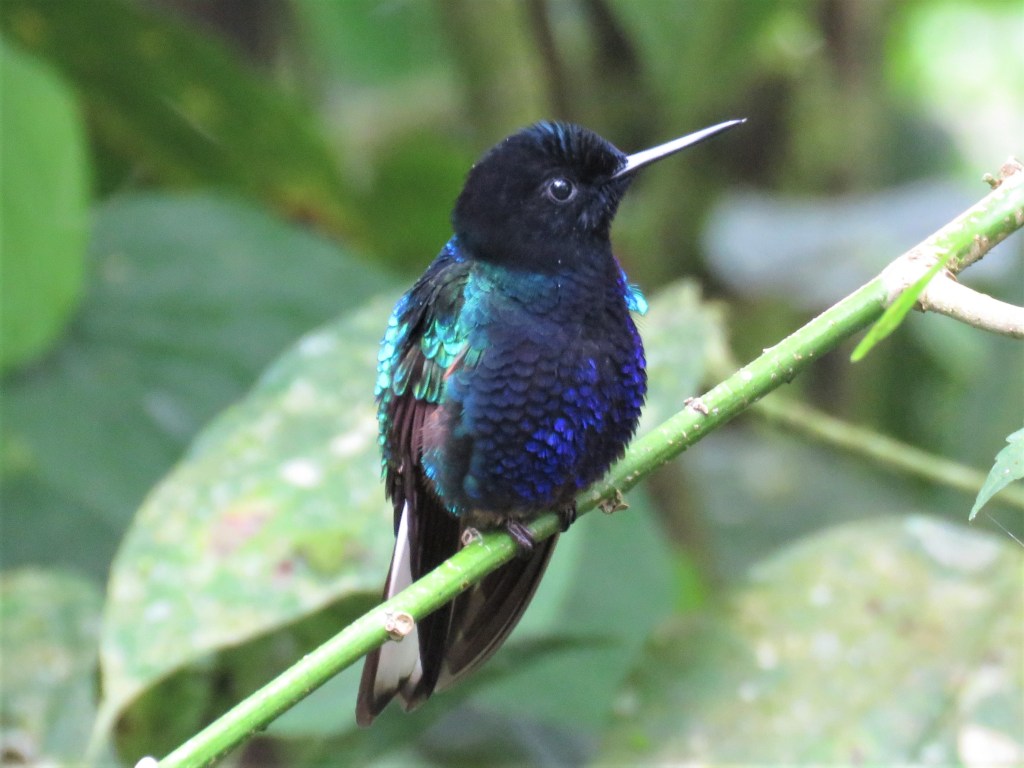

Every day this month we saw White-necked Jacobins, (Green) Crowned Woodnymphs, Fawn Breasted Brilliants, Green Crowned Brilliants, White-whiskered Hermits, and Purple-bibbed Whitetips. Even though they’re common for us here at RLT, they’re each rather stunning birds in plumage, size, and habits. Yesterday had some nice surprises: a male Booted Racket-tail came around a few times, a very small hummer with big white boots (made of rabbit fur, by the looks) and a relatively long motmot-type tail that ends in paddle-shaped feathers. Also, my only sighting of a female Violet-tailed Sylph was a delight (despite the female operating without that outrageous 8-inch violet tail that males wield). We also had one of only 4 viewings this month of a Brown Violetear. Not quite as infrequent (9 viewings in 29 days), but perhaps the most multi-colored visitor is the Velvet Purple Coronet—so regal in his (or her) purple robe and golden-coppery wings. Also, this coronet is endemic to the Choco-Andean ecosystem and I have a book that tells me it’s listed as “threatened” with extinction. So we’re always stoked to see it.

How do you feel about feeding these hummingbirds sugar water?

Dang, tough question. Are we supplying an artificial food source to wild birds? Yes. Does it create an “unnatural” environmental situation? Probably in this immediate area, in that the hummers do get accustomed to the red feeders and seem to organize social hierarchies to defend this “territory” and food source that we’ve manufactured. But to ask: are any species or individual hummingbirds somehow losing what it takes to make it in the wild, or does this intervention favor one species over another at the population level…? That seems doubtful to me. But RLT in part exists for researchers to pose such questions and develop field methods to test possible answers. Inquiries and Investigators welcome!

That said, it is flowering plants that we want our hummingbirds to be nourished by, so at RLT we see that interaction in the profusion of flowing plants right now in our protected forests, as well as in the handful of “hummingbird plants” that we’re propagating in the garden areas around our Lodge. Still, there is some self-serving-for-the-human-soul aspect of the hummingbird feeders, in that it brings us into very close relations with individual birds. For example, there’s a male Purple-bibbed Whitetip that greets us first thing in the morning, and will perch on the rim of my red coffee mug while I raise it to my lips. And there’s a female Green-crowned Brilliant that Anastasia rescued from inside the Lodge, that will perch close to the deck and chat something that sounds to me like appreciation and kinship conversation. So we do get to know these birds as individuals, thanks to the practice of giving them a sugar high and staring at them through binoculars for an hour each day. It’s great fun to share this with guests and volunteers—come visit, we do this every morning!

Speaking of the plant-and-hummingbird interactions, are there any final observations to share?

For sure. First, there are a handful of hummingbird species that I see around the Reserve, and which are almost never recorded in our daily feeder surveys. The Purple-throated Woodstar will buzz like a bumble bee up to the Verbena shrubs near our front deck most mornings, but we’ve never observed it at the feeders 20 meters away. The heart-achingly named Tawny-bellied Hermit is a striking bird from tip to tail, who I mostly see when I’m alone in the forest, looking up at a flowering epiphyte to notice her feeding naturally. Violet-tailed Sylphs favor the flowers of what I might commonly call a flowering maple, which we’re propagating around the perimeter of the gardens around the Lodge.

And I guess a highlight moment from this month occurred when I was hiking the Quetzals trail. As the trail climbs out of a dense forested area into a sunny zone where there is a grand patch of unusual red-stemmed shrubs (Malvaceae Werklea ferox), which towered 12 feet into the air with a profusion of large, bristly red flowers. Realizing I hadn’t seen this species of plant elsewhere on the Reserve, and appreciating catching it in full bloom (in morning sunlight, no less), I spotted a hummingbird that was new to me, feeding from flower to flower. With a short bill, glistening rosy throat and a distinct white crescent bib, I observed his behaviors closely at first, and while fumbling for my phone to snap a photo, I looked up and he was gone. Still, every time I walk through that patch of flowers now I wistfully hum a few bars from my 437th favorite Bob Dylan song, “You (Gorgeted Sun)Angel, You.”

~Jason Rainey, current co-manager/volunteer caretaker of Reserva Las Tangaras

AWESOME BLOG! Super insightful and true. Love it.

LikeLike